Singapore: A farce, a charade, a sham. The response from human rights groups to the United Nations interrogation of allegations of human rights abuse in China has been visceral and swift.

The UN Human Rights Commissioner gained access to China for the first time in 17 years. On Saturday night in Guangzhou, Michelle Bachelet appeared willing to discuss anything but the details of her trip to Xinjiang. Rising wheat prices, global oil shortages, the Texas school shooting, and the situation in Yemen, Ukraine and Myanmar – all of them were raised during Bachelet’s late-night press conference.

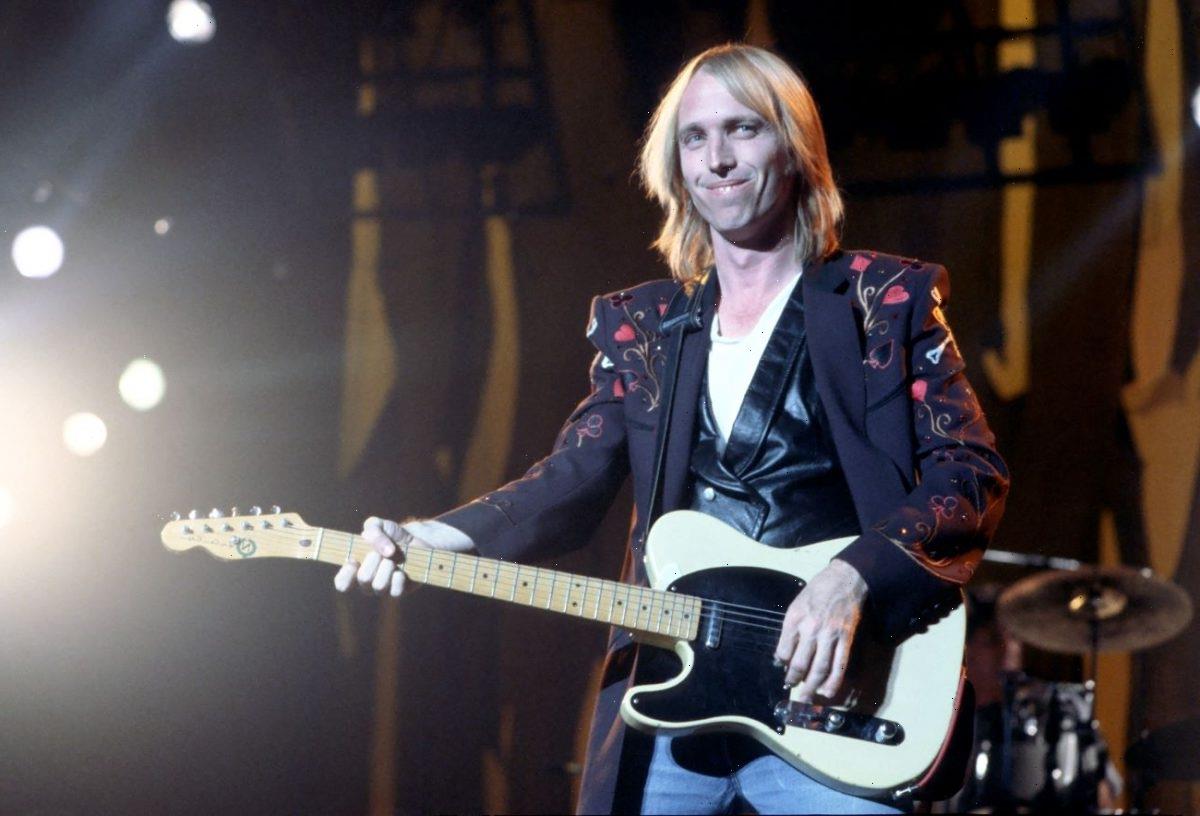

UN human rights chief Michelle Bachelet.Credit:AP

Bachelet praised China for improving women’s rights, living standards and alleviating poverty, but said she was “unable to assess” whether human rights violations had taken place in Xinjiang in vocational training centres under what she described as China’s anti-radicalisation and counter-terrorism measures.

Uighurs call them prisons filled with parents, brothers and sisters – detained for discussing Islam on WeChat, “gathering in groups”, or downloading an app. Others like Uighur woman Mihrigul Tursun say they have been stripped naked, raped, electroshocked and beaten while interrogated.

The evidence and allegations of abuse in Xinjiang are so comprehensive that perhaps no response from the UN would satisfy human rights groups and the families of up to 1 million Uighurs who have been put through “re-education camps”.

To this Bachelet could only say that she had heard from some Uighur families now living abroad who have lost contact with their loved ones.

“In my discussions with the authorities, I appealed to them to take measures to provide information to families as a matter of priority,” she said. Bachelet confirmed that she had not seen any operational detention centres but said she had been assured that the “vocational education” system has been dismantled. She did not elaborate on why, if the training had been so beneficial, it had to be destroyed.

On Hong Kong, where the political opposition has been eliminated, activists imprisoned, and independent media shut down, Bachelet said it was “important that the government there do all it can to nurture – and not stifle – the tremendous potential for civil society and academics in Hong Kong to contribute to the promotion and protection of human rights in [Hong Kong] and beyond”.

She spent more time during her press conference on human rights in China suggesting an erroneous link between race relations in the United States and the mass school shooting in Texas that left 21 dead.

“The killing in Texas was very sad,” she said. “It shows that the problem is not solved and that everybody needs to continue struggling against racial discrimination against people who believe that their superiors and others will feel they have the right to kill other people because they’re not this racial superiority.”

The comments were repeated on Sunday by Chinese state media as evidence of the US’s systematic discrimination in contrast with the “rampant disinformation on Xinjiang”.

Bachelet, on Chinese soil, may have felt the pressure to tell a story the Chinese government wanted to hear. But to the outside world, it verged on sycophancy. “Broken,” said the China director of Human Rights Watch Sophie Richardson.

The UN now faces a deep credibility challenge. China has put it at the centre of its vision for a UN-led multilateral order and is its second-largest financier. UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres was the guest of honour alongside Vladimir Putin at the Beijing Winter Olympics. In 2019, it removed a judge from the case of a whistleblower who had accused the global body of passing on information to Beijing about Chinese dissidents. China has since secured one of five seats on the panel that picks UN human rights abuse rapporteur and currently controls the top positions in three of the UN’s agencies across agriculture, telecommunications, and aviation.

Philip Alston was the last UN special rapporteur to visit China in 2016. The Chinese government made it clear to the Australian international lawyer that meetings with sensitive persons and on sensitive issues were off limits. A Chinese lawyer who met with him was arrested after his visit. Their phones were all bugged.

“There was a phone mechanic in the room of one of my colleagues when she first arrived at our hotel,” Alston said of his visit on Saturday. “The mechanic reported that the problem was assigned, and he was very helpfully there to repair it. I’m sure that all the phones in the high commissioner’s party will have also been repaired.”

Chinese President Xi Jinping, right, holds a virtual meeting with United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet. Credit:AP

“It was extremely difficult to have anything like what would pass for a conversation that was free and voluntary and open,” he said. “Those are the realities of a visit to China.”

Given those challenges, Alston said the purpose of Bachelet’s visit is not to interrogate but to open channels of communication with the Chinese leadership.

“The mere fact that she had a direct exchange with President Xi Jinping is an accomplishment,” he said.

It has been four years since the UN announced it would investigate the allegations of human rights abuse in Xinjiang. In September, Bachelet said she was finalising its investigation and preparing to make her findings public.

More than eight months later there is still no formal report and no date on its release. On Wednesday, she got a Zoom with the President.

Get a note directly from our foreign correspondents on what’s making headlines around the world. Sign up for the weekly What in the World newsletter here.

Most Viewed in World

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article