On the tenth anniversary of Mel Smith’s death, GRIFF RHYS JONES pays tribute to the masterful comedian

I was genuinely startled last week when an old friend rang me out of the blue to say it was now ten years since Mel Smith died. I don’t mean I was surprised he got in touch. He didn’t want me to go and lay a wreath or anything.

I just couldn’t believe that it was ten whole years since July 2013, on a day just like this, a bit overcast with wood pigeons practising their school recorder scales outside, when I noticed my wife Jo had dropped her voice in the room next door and was saying things like, ‘oh, I’m so sorry to hear that…’ and ‘if there is anything we can do…’

Shamefully, I thought, ‘hello, one of her elderly cousins…’ I was already sneaking out to join the wood pigeons when she told me Mel had gone. It was the unexpected news that, in truth, we had all been half-expecting. Mel was dead. It was a heart attack in his sleep, after a bad period of illness. He was 60.

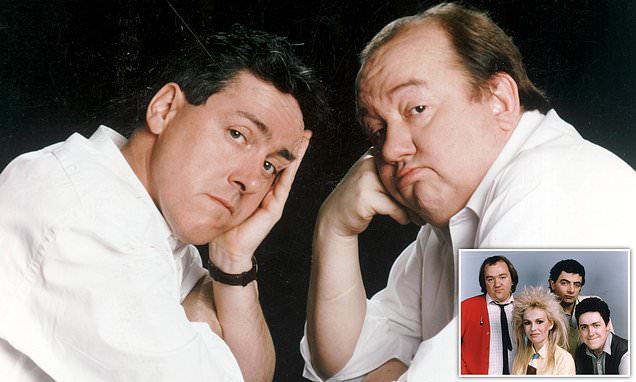

Mel Smith and Griff Rhys Jones in a scene from TV programme ‘Smith and Jones’

Ten years before that, I had stood up at his 50th birthday party and got a cheap laugh by saying how amazed we were that he had made it as far as that. It was a crack. Nobody had seriously thought Smudger, Cecil B. De Mel, Melvyn Kenneth would fail to last another decade.

He and I had finally stopped gibbering at each other across a darkened TV studio back in 1997. Mel retreated to his vodka and cranberry juice mansion in St John’s Wood, West London, and I went off to ponder alternative Farrow & Ball paint colours just down the road. We never really worried about each other after that. But we kept in touch.

Around Christmas 2012, I arranged a special yuletide lunch — Mel loved an afternoon-long restaurant event as much as any other thing in life, short of the Grand National. This one was especially sweet because I was going to pay for it.

But he didn’t turn up. He was in hospital and in a very poor state. None of us, his best friends, knew. Legend has it that he had been lying in a coma on the floor of the bathroom for 36 hours. The cleaning lady had come and gone but she didn’t disturb him because she assumed he was sleeping it off.

Mel was a night person. He always had been. When I first met him, when we were both recruited to Not The Nine O’ Clock News in 1979, I got quickly ‘Smithed’, as the office called it. This was Mel the dark planet, the black hole, whose mesmeric gravitational pull sucked unwary smaller planets into his orbit.

Leading journalists, novelists, Hollywood actors… me. You were suddenly out with a bloke who didn’t go to bed. He went to the Kensington Roof Gardens instead. He didn’t have a nightcap, he cranked up his evening.

And then, after the rooftop nightclub, you went back to his place and you played poker and laughed, and then you listened to a favourite record seven times in a row and laughed a lot more, and then you watched your favourite bits of the Godfather and then you opened the seventh bottle of champagne. And you laughed and laughed all night. And you thought this is really it. What’s happened to me? I’ve become a silly old stuffy middle-aged straight before my time. Just cos I’ve got a job. Or a wife. Or a mortgage. This is what I really am! Onwards!

For a few, these escapades lasted three nights. Some initiates managed a month with rests. But their eyes gradually became fixed pools of beady intensity and then they knew they were done.

During the 1980s, Mel Smith was a one-man recruiter for AA. Hardened professional drinking men — and it wasn’t all men but largely tended to be — would ultimately crumple, implode and crawl home sobbing. But not Mel. He was entirely sympathetic and caring. He might even help you back to your crib but he just carried on. He would quicky replace you with another inland-sailor candidate and go once more a’roaming.

Through 1981 and 1982, I loved being Smithed. I became teetotal in April 1983. I haven’t touched a drink since.

Not the Nine O’Clock News comedy foursome Mel Smith (back, left), Rowan Atkinson (back, right), Pamela Stephenson (front, left) and Griff Rhys Jones (front, right)

One of the miracles of our 30-year bond thereafter, was that Mel carried on drinking and partying and I just watched — not from the sidelines, as it were, but right in there, sitting on the same sofa, on his metaphorical knee, right through a long rocketing business and performance career, sharing jokes, caravans, friends and laughter but never a single bottle of anything.

Mel was like an elder brother to me; inclined to pinch things and pat me on the head.

We had different tastes. He would bet on two raindrops on a window, if he could. Once, when we toured, I persuaded him that a night in a Scottish country hotel would be a charming alternative. He grumbled. We checked in. They were serving dinner at six o’clock. Mel looked aghast and ate two.

Later, when we finished the show in Aberdeen, we drove back and found the entire place locked at 10.30pm. We banged on the door and hollered. Lights in distant towers went on. The porter came down. ‘Who’s that knocking?’

We annoyed him by putting another tree on his baronial fire and drinking whiskies until late. Back in his room, Mel rang room service. ‘Oh my Lord. What’s the trouble?’ It was the night porter.

‘I want a bottle of champagne.’

‘What! It’s one o’clock in the morning. I am not here to bring you bottles of champagne, young man,’ said the night porter. ‘I am only here for emergencies.’

‘This is an emergency,’ said Mel. ‘I need an emergency bottle of champagne.’ We never stayed anywhere but a Thistle or a Hilton again.

It was tragic that he died. We all thought that. But for me it got worse. First of all, for 30 years, he had never really obsessed me.

You know, he was as loyal as a water buffalo, as robust as the Incredible Hulk (sometimes as green too) and with the appearance of a faded Cabbage Patch Doll, and I had got used to letting him go his own way.

But, now that he was dead, Mel started to turn up in my dreams. I am backstage, in a panic, pushing through black heavy drapes, trying to find him.

‘Mel, Mel, we are about to go on stage…’ I can hear the murmur of 3,000 restless people. I need to find out what we are going to actually do or say! Help me!! This is a familiar actor’s nightmare. But, for me, it had been the reality. Mel always hated practice. He just stood there and did the performance. He had a photographic memory. We never got a full run at anything.

Griff Rhys Jones (L) and Mel Smith (R) in rehearsals for TV series entitled ‘The World According To Smith and Jones’

The script stayed in his hand and he’d read from it until the end of camera rehearsal in the studio — around 6.30pm.

He’d get a plate of BBC moussaka, switch the telly on in his dressing room and have the entire thing off pat by 7.30pm.

I arrived to perform at Live Aid (1.5 billion audience) and waited for him in the cafe while pop star entourages came and went, like medieval popinjay courtiers, and he finally ambled in a few minutes before we were due on stage. ‘Where’s the script then?’

I had worked something out but there was no time to rehearse it. We introduced Queen dressed as two policemen. (‘We’ve had a complaint about the noise etc…’) It was fun, if a little scary.

We ended up in the VIP section with Princess Diana and we settled into the best seats to watch Elton John blast off what might have been his first farewell tour.

Mel sighed a bit, looked at his watch. ‘Well, I’m off then.’

‘You’re going?’

‘Yeah.’

‘But, Mel, this is the greatest rock and roll show in history, ever.’

I was shocked. I’d thought it was important. I’d skipped my son’s christening to be there.

‘I’ve got a horse running in Doncaster,’ Mel said, and left.

Generous, as always, he gave his Access All Areas pass to our manager.

And that’s why, if you look very closely, you can see a bloke called Peter Fincham singing Feed The World next to Roger Daltrey and Bob Geldof at the climax of Live Aid.

Stephen Fry, Ben Elton, Robbie Coltrane, Griff Rhys Jones, Mel Smith and Rowan Atkinson at the Bafta Awards, London, Britain – 1987

By the 1990s, Mel and the older Peter Cook adored a long afternoon together. Neither did much before lunch anyway. Afterwards, out came the Sporting Life and the vodka and on went the C4 racing. It was the ultimate urban recliner adventure. I am sorry to say that both died at about the same age.

You can’t really go on for ever, can you? Despite all the sage health advice in the Saturday pull-outs, no amount of carrots, body-weight exercises or mindfulness will really compensate for a 30-year all-out assault on the body’s capabilities.

Mel hit a rock that Christmas in 2012. He was told he probably wouldn’t walk again. I was told that the nurses watched in astonishment when he confounded medical opinion by doing a Douglas Bader and used those parallel pole things to get his legs working again. As soon as his pins were up to it, he walked straight out of the ward and hailed a taxi.

‘He’s at home with the racing on,’ his stepson told me. ‘He’s sitting with the Sporting Life and a beer.

‘Oh no. Not a beer.’

‘It’s just a beer.’

He’d been through the cold turkey on the ward. While he was there, I had convened a little wise council of some of his oldest companions to see if we could persuade him by some means to stay ‘clean’. But you can’t get someone on the strait and narrow if they don’t want to leave the shrubbery. You can’t get a horse to water and make him not drink.

Mel never left any party before dawn and never early, except, in the end, the biggest party of all — life itself.

Apart from his haunting my recent dreams, I think of him often. I was watching the Steve Coogan Laurel And Hardy film on a plane coming back from Australia a few years ago and I started weeping. Seriously. I couldn’t believe it. I thought. Wow, that’s us.

I was Stan. Mel was Ollie.

Like Stan, I wrote. Like Ollie, he laughed at the scripts.

I dealt with the producers. He left me to it.

I fretted, he relaxed.

I was out with our friend and fellow comedian Rory McGrath. We were getting ready for my annual Christmas party. A crisp, cold early evening in London. We stopped, and I said: ‘You know what, Rory, this is a great night to be alive.’

If I tell you we were in the middle of Tottenham Court Road dodging chuggers, you will understand what a good mood I was in.

‘I can’t believe that Mel is missing all this.’

Because the last ten years have indeed been life, life, life. It has been said that grumpy old men only become really happy in their 60s. Of course they do. They can really enjoy their grumpiness.

I can’t be bothered to fret about the deranged loonies who run television and whether they want me or not. I’m happy to take on all the middle-aged pleasures: walks, online auctions, visiting churches, bowling lanes, the Waitrose cafe.

God knows, one day, if things get really bad and I have absolutely nothing left in life to do, I might even try golf.

I have grandchildren, another two baby girls a fortnight ago, and my heart is bursting.

It’s tragic that Mel went so early. He has missed so much. He missed his own obituaries: amazingly respectful. He’d have been astounded. And that movie we wrote together. One review at the time began: ‘Die before you see this film.’ And that was one of the better ones. But Mel missed a special showing of Morons From Outer Space at the Prince Charles cinema a few years ago in front of a wild audience of whooping addicts.

He missed the BFI publishing a bloody book hailing it as one of the great misunderstood films of the era: way ahead of its time.

At least Mike Hodges, the great director, and I were able to sit there with our jaws open and eyes popping, like extras in The Producers.

Worst of all, he missed out on his free Oyster card. If you live in London and reach 60, you get to travel on the buses and the Underground for nothing, Mel. It was a mad idea that Ken Livingstone had to help millionaires like me.

Mel loved public transport. He was never out of a black cab. I don’t imagine he’d have ever got on a bus, but he might have tried to hail one.

The One Griff Rhys Jones. Mel Smith

He shall not grow old as we that are left grow old. He shall not grow runner beans, either. He shall not grow an enlarged prostate. But he should have had another ten years. He would have enjoyed it, too.

He was a totally generous performer. I have never played with anyone who was so instantly together and up for it, and with you. Fuss-free was our performing motto. If either of us thought the other should do something different we just told them.

Ninety per cent of proper theatre rehearsals with sensitive actors can be total garbage fuss.

I leave it to other people to decide whether we were funny at all, but we both laughed a lot on the way.

Source: Read Full Article