- Already in the first few months of 2021, new findings about the Tyrannosaurus rex have shifted paleontologists’ picture of how the dinosaur hunted, moved, and grew into a fearsome predator.

- Examinations of adult T. rex skeletons have revealed that the animal preferred to walk slowly and couldn’t run.

- Researchers also determined that the T. rex developed stiff, bone-crushing jaws once it became an adult, after experiencing a huge growth spurt during its teenage years.

- The previously held idea that this type of dinosaur preferred a solo lifestyle has also been called into question: A recent fossil finding suggests a pack of Tyrannosaurs died together while hunting.

- See more stories on Insider’s business page.

When the T. rex starred in Steven Spielberg’s blockbuster “Jurassic Park” in 1993, only seven or eight T. rexes had been uncovered. The very first was discovered in 1902.

But in the 25 years since the movie came out, scientists have found dozens more T. rex skeletons, and that has helped sharpen our understanding of how these animals hunted and moved.

In total, 32 adult rex skeletons have made it into public museums worldwide for scientists to study.

Already in the first four months of 2021, a handful of discoveries have further confirmed the ways in which the T. rex in “Jurassic Park” didn’t resemble its real-life counterpart.

For starters, scientists confirmed that T. rexes were so massive, they couldn't run without hurting themselves.

A fully grown T. rex is one of the largest carnivorous land animals to ever walk the Earth, standing about 12 to 13 feet tall at the hip and measuring up to 43 feet from tooth to tail. An adult could weigh between 5.5 and 9 tons.

But that size brings certain drawbacks: A bone can only handle so much pressure while running before it breaks. One study found that if a T. rex moved any faster than 12 mph, the predator’s bones would have shattered.

So the iconic "Jurassic Park" scene in which a T. rex chases down three park visitors driving away in a Jeep wasn't accurate.

In fact, the T. rex preferred to walk slowly, according to a study published last week that reconstructed the animals’ tails to calculate a T. rex’s natural step rhythm.

You could probably out-walk a T. rex, or at least keep up with one, according to Pasha van Bijlert, a paleobiomechanics expert who co-authored that study.

The T. rex most likely preferred to walk at a leisurely 3 miles per hour — "that's basically the speed at which T. rex would take a stroll," van Bijlert told Insider.

That’s just under the average preferred walking speed for a human.

This slow speed likely meant it took a T. rex a while to forage for food, find water, and scout out an area, according to van Bijlert.

Another study published this month calculated that a single adult T. rex lived in an area roughly 40 square miles in size.

That means a territory the size of Manhattan or San Francisco would have been necessary to sustain just one adult rex. Surveying an area that large could have taken a T. rex more than 13 hours.

Based on that territory size estimate, a group of scientists from the University of California calculated the total number of adult T. rexes that ever walked the Earth: a whopping 2.5 billion.

The researchers found that about 20,000 adult T. rexes could have been alive at any given time in the species’ existence.

“The total number did catch me off guard,” Charles Marshall, a paleontologist at the University of California, Berkeley, who co-authored the research, previously told Insider.

By looking at the average time span between when rexes became fully grown and when they died in their early 30s, Marshall calculated that about 127,000 generations of T. rexes could have lived on Earth. Multiply that number by 20,000 per generation, and you wind up with 2.5 billion adult T. rexes that lived and died on Earth roughly 66 to 68 million years ago.

The calculation helped Marshall answer a question that had been gnawing at him: "When I hold a fossil in my hand, I've always said to myself, 'I know this is freakishly rare.' But just how rare is it — one in a million or one in a trillion?"

His recent analysis suggests that the T. rex skeletons discovered so far represent just one in every 80 million adult rexes that ever roamed the planet — a paltry 0.00000125%.

If adult T. rexes are an incredibly rare find, fossils from juvenile rexes — which were svelter than their full-grown counterparts — are even rarer.

It took a T. rex 20 years to grow from a tiny hatchling to a 9-ton predator with teeth that could crush bone. Most of that growth happened between the ages of 14 and 18, when the dinosaur’s body size doubled.

A juvenile rex was so small relative to an adult that when paleontologists first found a couple juvenile skeletons, they thought the fossils belonged to a different pygmy T. rex species.

That agile, compact size afforded juveniles certain hunting advantages: Younger rexes could run, and therefore hunt different prey than adult rexes.

A juvenile rex hunted faster, smaller prey, in part because it didn’t have had the power of an adult’s bite.

An adult rex had a bite force of 7,800 pounds, which could crush a car. No other known animal in history could bite with such force. That’s why full-grown T. rexes could hunt giant prey like triceratops or duck-billed dinosaurs.

Younger rexes had serrated, knife-like teeth instead.

Paleontologists had long wondered how a T. rex could bite through solid bone without breaking its own skull. New research offers an answer.

That research, presented earlier this month, found that the T. rex had specialized bones that helped to stiffen its lower jaw when it bit down. A paper published in March showed that the dinosaur’s stiff lower jaw only developed once a T. rex finished its teenage growth spurt and became a fully grown adult.

Mostly likely, the T. rex had a rigid skull like those of modern-day crocodiles and hyenas, rather than a flexible one like birds and reptiles. That’s how the dinosaur could bite down on its prey with the weight of about three Mini Coopers.

These new findings build on other research about the differences between how adult and juvenile T. rexes hunted.

Because rexes’ bodies, movement, and teeth changed so much as they grew up, younger and older rexes didn’t have to compete for prey.

Prior to their growth spurts, juvenile T. rexes could move faster than adults because they were more lightly built. If a grown T. rex wanted to pursue prey, it could only move at speeds between 10 and 25 mph for brief stints.

“They go through a drastic change when they grow up, from these sleek, slender, fleet-footed T. rexes with these wonderful knife-like teeth to these big, monster, plodding, crushing tyrannosaurs that we are familiar with,” Scott Williams, a paleontologist from New York University who co-authored a study about this, told Insider last year.

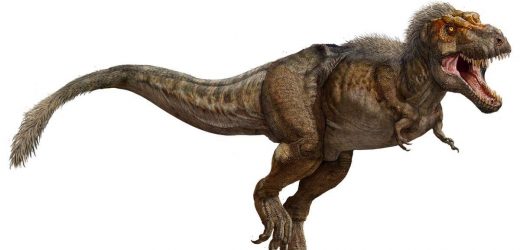

Juvenile and adult rexes differed in looks in addition to size. Young rexes were covered in feathers for warmth and camouflage.

An adult T. rex, on the other hand, rocked a mullet of feathers on its head, neck, and tail, according to paleontologists from the American Museum of Natural History.

Still, Williams said, “these animals probably dominated their ecosystems at all ages.”

Other tyrannosaur species were a predatory tour de force, too. Some of the T. rex's cousins may have hunted in packs like wolves.

Paleontologists recently discovered a handful of tyrannosaur skeletons in Utah’s Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. These aren’t T. rexes: The tyrannosaur category includes similar two-legged carnivores like Albertosaurus and Gorgosaurus as well.

A recent study about the fossil finding suggests that a pack of dinosaurs all died at the same time, perhaps while hunting together — which would mean not all tyrannosaurs were solitary predators in the way experts thought. Instead, some may have been social animals that worked together, like modern-day birds.

Source: Read Full Article