Antarctic ice shelf is crumbling much FASTER than we thought, with 12 TRILLION tonnes of ice lost since 1997 – double the previous estimate, NASA reveals

- NASA researchers say Antarctic ice shelf is crumbling much faster than thought

- Raises new concern about how fast climate change is weakening the ice shelves

- Not only that, but also how much this is accelerating the rise of global sea levels

- First-of-its-kind study was led by scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory

The Antarctic ice shelf is crumbling much faster than first thought, a NASA study has revealed, with 12 trillion tonnes of ice being lost over the past 25 years.

That is double the previous estimate — raising new concern about how fast climate change is weakening the continent’s coastal glaciers and accelerating the rise of global sea levels.

The first-of-its-kind study, led by researchers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), used satellite data to reveal that icebergs are being shed more rapidly than nature can replenish the melting ice.

They said Antarctica was ‘crumbling at its edges’ and the consequences could be enormous.

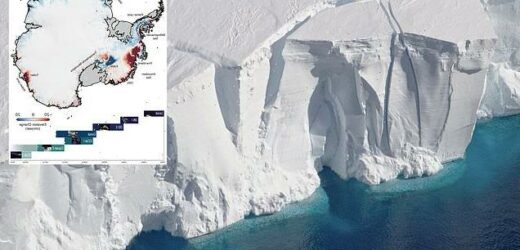

Melting: The Antarctic ice shelf is crumbling much faster than first thought, a NASA study has revealed. In this 2016 photo the 200ft-tall front of the Getz Ice Shelf in Antarctica is scored with cracks where icebergs are likely to break off, or calve

GLACIERS AND ICE SHEETS MELTING WOULD HAVE A ‘DRAMATIC IMPACT’ ON GLOBAL SEA LEVELS

Global sea levels could rise as much as 11ft (3.3 metres) if the Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica collapses, previous research has suggested.

Sea level rises threaten cities from Shanghai to London, to low-lying swathes of Florida or Bangladesh, and to entire nations such as the Maldives.

In the UK, for instance, a rise of 6.7ft (2 metres) or more may cause areas such as Hull, Peterborough, Portsmouth and parts of east London and the Thames Estuary at risk of becoming submerged.

The collapse of the glacier, which could begin with decades, could also submerge major cities such as New York and Sydney.

Parts of New Orleans, Houston and Miami in the south on the US would also be particularly hard hit.

Researchers said their key finding was that the net loss of Antarctic ice from coastal glacier chunks ‘calving’ off into the ocean is nearly as great as the net amount of ice that scientists already knew was being lost due to thinning caused by the melting of ice shelves from below by warming seas.

Taken together, thinning and calving have reduced the mass of Antarctica’s ice shelves by 12 trillion tons since 1997, double the previous estimate, the analysis concluded.

The net loss of the world’s largest ice sheet from calving alone in the past quarter-century spans nearly 14,300 sq miles (37,000 sq km), an area almost the size of Switzerland, according to JPL scientist Chad Greene, the study’s lead author.

‘Antarctica is crumbling at its edges,’ Greene said.

‘And when ice shelves dwindle and weaken, the continent’s massive glaciers tend to speed up and increase the rate of global sea level rise.’

The consequences could be huge because Antarctica holds 88 per cent of the sea level potential of all the world’s ice, he said.

Ice shelves, permanent floating sheets of frozen freshwater attached to land, take thousands of years to form and act like buttresses holding back glaciers that would otherwise easily slide off into the ocean, causing seas to rise.

When ice shelves are stable, the long-term natural cycle of calving and re-growth keeps their size fairly constant.

In recent decades, though, warming oceans have weakened the shelves from underneath, a phenomenon previously documented by satellite altimeters measuring the changing height of the ice and showing losses averaging 149 million tons a year from 2002 to 2020, according to NASA.

For their analysis, Greene’s team used satellite imagery from visible, thermal-infrared and radar wavelengths to chart glacial flow and calving since 1997 more accurately than ever over 30,000 miles (50,000 km) of Antarctic coastline.

The losses measured from calving outpaced natural ice shelf replenishment so greatly that researchers found it unlikely Antarctica can return to pre-2000 glacier levels by the end of this century.

The accelerated glacial calving, like ice thinning, was most pronounced in West Antarctica, an area hit harder by warming ocean currents.

But even in East Antarctica, a region whose ice shelves were long considered less vulnerable, ‘we’re seeing more losses than gains,’ Greene said.

One East Antarctic calving event that took the world by surprise was the collapse and disintegration of the massive Conger-Glenzer ice shelf in March, possibly a sign of greater weakening to come, he added.

Eric Wolff, a Royal Society research professor at the University of Cambridge, pointed to the study’s analysis of how the East Antarctic ice sheet behaved during warm periods of the past and models for what may happen in the future.

‘The good news is that if we keep to the 2 degrees of global warming that the Paris agreement promises, the sea level rise due to the East Antarctic ice sheet should be modest,’ Wolff wrote in a commentary on the JPL study.

Failure to curb greenhouse gas emissions, however, would risk contributing ‘many meters of sea level rise over the next few centuries,’ he said.

The new research has been published in the journal Nature.

Antarctica’s ice sheets contain 70% of world’s fresh water – and sea levels would rise by 180ft if it melts

Antarctica holds a huge amount of water.

The three ice sheets that cover the continent contain around 70 per cent of our planet’s fresh water – and these are all to warming air and oceans.

If all the ice sheets were to melt due to global warming, Antarctica would raise global sea levels by at least 183ft (56m).

Given their size, even small losses in the ice sheets could have global consequences.

In addition to rising sea levels, meltwater would slow down the world’s ocean circulation, while changing wind belts may affect the climate in the southern hemisphere.

In February 2018, Nasa revealed El Niño events cause the Antarctic ice shelf to melt by up to ten inches (25 centimetres) every year.

El Niño and La Niña are separate events that alter the water temperature of the Pacific ocean.

The ocean periodically oscillates between warmer than average during El Niños and cooler than average during La Niñas.

Using Nasa satellite imaging, researchers found that the oceanic phenomena cause Antarctic ice shelves to melt while also increasing snowfall.

In March 2018, it was revealed that more of a giant France-sized glacier in Antarctica is floating on the ocean than previously thought.

This has raised fears it could melt faster as the climate warms and have a dramatic impact on rising sea-levels.

Source: Read Full Article