Roman settlement's 'decline' discussed by historian

We use your sign-up to provide content in ways you’ve consented to and to improve our understanding of you. This may include adverts from us and 3rd parties based on our understanding. You can unsubscribe at any time. More info

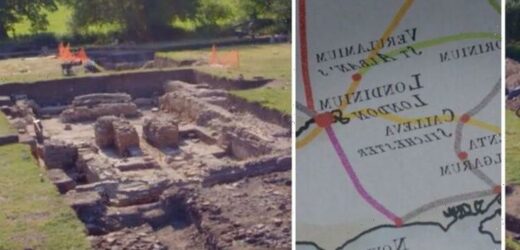

Calleva Atrebatum was once an Iron Age settlement, serving as the capital for the Atrebates tribe. Upon the Roman conquest of Britain in 43AD it developed into the Roman town that it remains today. It grew in size, had several public buildings and flourished until the early Anglo-Saxon period.

Calleva, sitting a few miles north of modern day Basingstoke, was a major crossroads in Roman society.

The Devil’s Highway connected it to the capital of Londinium (London), and several other roads stemmed west from Calleva.

Among them was the road to Aquae Sulis (Bath); the Ermin Way to Glevum (Gloucester) and the Port Way to Sorviodunum (the old town of Old Sarum near modern day Salisbury).

However, after the Roman withdrawal from Britain, Calleva’s fortunes began to falter. Evidence of occupation begins to decline sharply after 450AD.

Archaeologists from Channel 5’s documentary ‘Digging Up Britain’s Past’ went to explore what happened.

Dr Hannah-Marie Chidwick, a Roman historian at the University of Bristol, explained that many Roman towns were built up around the roads.

Alex Langlands, archaeologist and co-presenter, questioned whether Calleva’s fortunes were bound to the fortunes of the roads.

Dr Chidwick replied: “Yes, so this is where it gets a bit interesting.

“By the third century, trade and industry at Silchester started rapidly declining.

“We also have archaeological evidence that the Romans started to decrease the width of their gates, and close them off into the town, which suggests that some of the roads were going out of use.

“Reasons for this might be that the Romans simply ran out of money, they stopped investing in public projects, and the money moves out to private villas and private land.”

Other Roman towns such as Canterbury and Winchester did not fall out of use, Mr Langlands argued, yet the Silchester site did.

DON’T MISS:

Archaeologists baffled by ancient rock art depicting ski figures [NEW]

Archaeologist stunned by War of Independence ‘trophy’ find [REPORT]

Archaeology: ‘Special’ Roman stamp gives ‘new information’ [INSIGHT]

Dr Chidwick continued: “So Silchester is not near a river or the sea. Silchester was basically nothing without those roads.”

Mr Langland added: “So when those roads start to fall into disrepair and decay, the writing’s on the wall for Silchester.”

That decline was a rapid one. Rome lost control of ancient Britain at the beginning of the fifth century when evidence suggests Silchester was still thriving.

Within 200 years of the end of Roman Britain, the town had gone completely.

Hypotheses have since emerged that the Anglo-Saxons deliberately avoided Calleva after it was abandoned, instead preferring to ensure the success of their existing strongholds at Winchester and Dorchester.

Several decades of excavations at Silchester have shown the signs of a rich and powerful town, with dense blocks of shops and houses, an amphitheatre, a temple and thermal baths.

A report published in The Guardian in 1999 reveals archaeologists found a series of bizarre burials, including the skeleton of a dog and a beef bone, which also contained broken pots already centuries old when they were buried in pits.

Archaeologists excavating the site believe these may point towards a ritual cursing of the site by the Anglo-Saxons.

Professor Michael Fulford, one of Britain’s leading archaeologists, said at the time: “The manner of its abandonment seems deliberate, signalling an intention never to return. If the occupation was ended in this way, does it not imply a deliberate ‘pollution’ of the site?”

The present day village of Silchester was founded around a mile to the west of the Roman town, where the earliest houses date back to the 17th and 18th centuries.

Around a century after Silchester’s abandonment, the Saxon towns of Basing — a village just east of modern Basingstoke — and Reading were built on rivers on either side of Calleva.

The first excavation at the Silchester site was carried out by Reverend James Joyce in 1861, but little further investigation occurred until 1961.

Since then, the University of Reading has excavated the site, publishing detailed studies of how the site might have once looked, and re-exploring previously excavated ruins to see what earlier excavators might have missed.

Source: Read Full Article