Christianity ‘turned to archaeology to promote bible’ says expert

We use your sign-up to provide content in ways you’ve consented to and to improve our understanding of you. This may include adverts from us and 3rd parties based on our understanding. You can unsubscribe at any time. More info

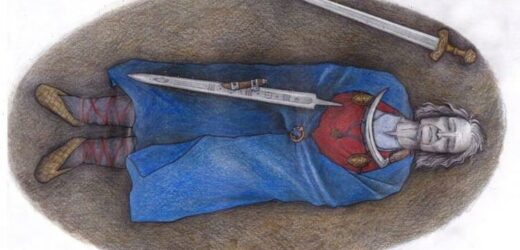

The unexpected breakthrough was made more than 50 years after archaeologists first discovered the famous Suontaka sword at a burial in Hattula, Finland. For decades, researchers had believed the 1,000-year-old grave had been occupied by two people – a man and woman – or a single woman of great stature. This was evidenced by a mix of male and female items like jewellery and clothing strewn across the grave.

If the burial was occupied by a single woman, Ulla Moilanen, a Doctoral Candidate of Archaeology from the University of Turku, argued this would have been a “highly respected” member of their community.

She said: “They had been laid in the grave on a soft leather blanket with valuable furs and objects.”

It was normal among Iron Age and Early Medieval communities in Finland to elevate women to positions of power and some were even warriors.

But a recent analysis of the limited DNA evidence available has exposed a much more surprising story behind the burial.

The burial was indeed occupied by a single individual, but the individual might have not been considered strictly a male or female, due to their genetic makeup.

The researchers’ analysis revealed the buried individual had a case of so-called Klinefelter syndrome.

According to the NHS, Klinefelter syndrome describes boys who are born with an extra copy of the female X chromosome.

Chromosomes are clusters of genetic material that carry your DNA and are responsible for the growth and production of organs, among other functions.

Women are typically born with two pairs of X chromosomes (XX) and men are born with one X and one Y chromosome (XY).

Valsgärde: Norwegian University make Iron Age discovery

Elina Salmela, a Postdoctoral Researcher at the University of Helsinki said: “According to current data, it is likely that the individual found in Suontaka had the chromosomes XXY, although the DNA results are based on a very small set of data.”

Klinefelter syndrome manifests in people in various ways and may sometimes even go unnoticed.

In other cases, young men may experience slower muscle growth, reduced facial hair and weaker bones.

In adult men, the syndrome may result in enlarged breasts (gynecomastia), lower sex drives, taller-than-average height and infertility.

In the case of the Suontaka burial, the individual may have lived outside of the accepted gender norms of the time.

Ms Moilanen said: “If the characteristics of the Klinefelter syndrome have been evident on the person, they might not have been considered strictly a female or a male in the Early Middle Ages community.

“The abundant collection of objects buried in the grave is proof that the person was not only accepted but also valued and respected.

“However, biology does not directly dictate a person’s self-identity.”

The study has also revealed one of the two swords originally found in the grave was actually placed there during the burial.

The bronze-hilted Suontaka sword was likely added to the site at a later point.

The other sword, which had its hilt removed, was placed on the buried individual.

Ms Moilanen said: “This also emphasises the importance of the person and their memory for their community.”

The study was published in the peer-reviewed European Journal of Archaeology.

Source: Read Full Article