Is this the key to staving off dementia? Blood from ultra-fit ‘marathoner’ mice boosts brain function in their couch-potato counterparts, study finds

- Blood from ultra-fit mice can boost brain function in couch-potato counterparts

- Their memory improved largely thanks to a single inflammation-fighting protein

- Blood of older people who had exercised showed a rise in levels of same protein

- The research could one day help point to new dementia treatments for humans

Blood from ultra-fit mice has been found to boost brain function in their couch-potato counterparts, in a discovery that could one day lead to new dementia treatments for humans.

Research found that injections of blood from young adult mice that were getting lots of exercise benefited the brains of sedentary mice the same age.

A single inflammation-fighting protein called clusterin seemed largely responsible for the benefit.

Although experiments involving mice are not guaranteed to translate to humans, when researchers looked at the blood of older people who had carried out an exercise regime, they found that levels of the same protein had risen.

‘The discovery could open the door to treatments that, by taming brain inflammation in people who don’t get much exercise, lower their risk of neurodegenerative disease or slow its progression,’ said Professor Tony Wyss-Coray, of the Stanford School of Medicine in California, which carried out the research.

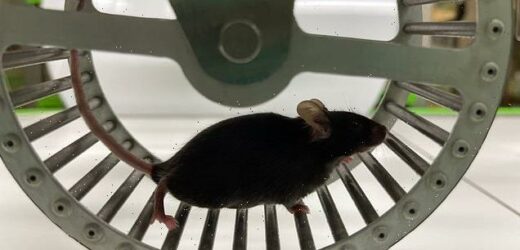

Study: Blood from ultra-fit mice has been found to boost brain function in their couch-potato counterparts, in a discovery that could one day lead to new dementia treatments for humans

WHAT THE EXPERTS SAY TO DO TO STAVE OFF DEMENTIA

Dementia is an umbrella term for several brain diseases that affect memory, thinking and cognition.

Treatments such as donepezil (brand name Aricept), rivastigmine (Exelon) and galantamine (Reminyl) help with symptoms but tend to become less effective as the condition worsens over time.

So in addition to the usual lifestyle factors that we’re all advised to address, what other steps do the top dementia experts themselves take to ward off the disease?

In bed by 10pm for a good night’s sleep

Dr Ian Harrison, a senior research fellow at the Centre for Advanced Biomedical Imaging at University College London, who specialises in brain imaging, says: ‘When it comes to lowering my own dementia risk, I swear by a good night’s sleep. I used to go to bed later, but for the past three years I’ve been strict about going to bed at 10pm every day, even at weekends.’

Chew on mints with xylitol

Chris Fox, a professor of clinical psychiatry at the University of East Anglia Medical School, said: ‘I take good care of my teeth to reduce the risk of dementia.

‘I use mints containing xylitol [an artificial sweetener] to keep the microbiome, the community of bacteria in the mouth, healthy.’

It has been suggested that oral health may be linked to dementia as bacteria may trigger inflammation in the brain.

Avoid walking besides busy roads

Dr Tom Russ, director of the Alzheimer’s Scotland Dementia Research Centre, at the University of Edinburgh, said: ‘I make a conscious effort to avoid walking along main roads and find back street routes where possible.’’

Air pollution was added to the list of modifiable factors to reduce dementia by the Lancet Commission in 2020.

Halve alcohol intake

Professor Paul Matthews, a director of the UK Dementia Research Institute, said: ‘We’ve recently done a study that shows that there is an association between drinking alcohol and higher rates of brain volume loss.’

He added: ‘I have certainly reconsidered my own alcohol consumption since completing this study, and I’ve cut back to between seven and ten units a week, down from 14.’

Don’t add salt when cooking

Dr Sarah-Naomi James, a dementia research fellow at University College London, said: ‘I’m in my early 30s but I look after my physical health and I’m particularly careful about checking salt levels on packets. And I don’t add salt to food, either.

‘Blood pressure tends to rise with age, but there is something about what happens in mid-life that seems to be particularly important, although we don’t know what the mechanism is yet.

‘One theory, though, is the pulsating pressure damages the brain.’

It is already known that exercise induces a number of healthy manifestations in the brain, such as more nerve-cell production and less inflammation.

Wyss-Coray added: ‘We’ve discovered that this exercise effect can be attributed to a large extent to factors in the blood, and we can transfer that effect to a same-aged, non-exercising individual.’

In their study, researchers found that transfusing blood from the ‘marathoner’ mice reduced levels of inflammation in the brains of sedentary mice.

Anybody who has suffered from flu can relate to the loss of cognitive function that comes from a fever-inducing viral infection, according to Wyss-Coray.

He said: ‘You get lethargic, you feel disconnected, your brain doesn’t work so well, you don’t remember as clearly.’

That’s a result, at least in part, of the body-wide inflammation that follows the infection. As a person’s immune system ramps up its fight, the inflammation spills over into their brain.

Wyss-Coray added that a similar type of neuroinflammation has been strongly tied to neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s in humans.

The experiments hinged on the fact that mice love to run. Give a caged mouse access to a running wheel a few inches in diameter and, with no training or prompting, it will rack up 4 to 6 miles a night (they sleep by day).

If you lock the wheel, the mouse will log only a small fraction of that amount of exercise.

The investigators put either functional or locked running wheels into the cages of 3-month-old lab mice, which are metabolically equivalent to 25-year-old humans.

A month of steady running was enough to substantially increase the quantity of neurons and other cells in the brains of marathoner mice when compared with those of sedentary mice.

Next, the researchers collected blood from marathoner mice and, as controls, sedentary rodents.

Every three days they then injected other sedentary mice with plasma from either marathoner or couch-potato mice.

On two different lab tests of memory, sedentary mice injected with marathoner plasma outperformed their equally sedentary peers who received couch-potato plasma.

In addition, sedentary mice receiving plasma from marathoner mice had more cells that give rise to new neurons.

The tests involved assessing how well the mice were able to learn that a particular sound meant that the floor of their cage was about to deliver a small electric shock.

Researchers calculated this by looking at whether the mice ‘freeze’ and stay still when they realise a shock could be about to happen.

‘The mice getting runner blood were smarter,’ Wyss-Coray said. ‘The runners’ blood was clearly doing something to the brain, even though it had been delivered outside the brain.’

The researchers also found that removing a single protein, clusterin, from marathoner mice’s plasma largely negated its anti-inflammatory effect on sedentary mice’s brains.

No other protein the scientists tested had the same effect.

Clusterin, an inhibitor of the complement cascade, was significantly more abundant in the marathoners’ blood than in the couch potatoes’ blood.

Further experiments showed that clusterin binds to receptors that abound on brain endothelial cells, the cells that line the blood vessels of the brain.

These cells are inflamed in the majority of Alzheimer’s patients, said Wyss-Coray, whose research has shown that blood endothelial cells are capable of transducing chemical signals from circulating blood, including inflammatory signals, into the brain.

Clusterin by itself, even though administered outside the brain, was able to reduce brain inflammation in two different strains of lab mice in which either acute bodywide inflammation or Alzheimer’s-related chronic neuroinflammation had been induced.

Separately, the researchers found that at the conclusion of a six-month aerobic exercise program, 20 military veterans with mild cognitive impairment, a precursor to Alzheimer’s disease, had elevated clusterin levels in their blood.

Wyss-Coray speculated that a drug that enhances or mimics clusterin’s binding to its receptors on brain endothelial cells might help slow the course of neuroinflammation-associated neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

The research has been published in the journal Nature.

WHAT IS DEMENTIA? THE KILLER DISEASE THAT ROBS SUFFERERS OF THEIR MEMORIES

Dementia is an umbrella term used to describe a range of neurological disorders

A GLOBAL CONCERN

Dementia is an umbrella term used to describe a range of progressive neurological disorders (those affecting the brain) which impact memory, thinking and behaviour.

There are many different types of dementia, of which Alzheimer’s disease is the most common.

Some people may have a combination of types of dementia.

Regardless of which type is diagnosed, each person will experience their dementia in their own unique way.

Dementia is a global concern but it is most often seen in wealthier countries, where people are likely to live into very old age.

HOW MANY PEOPLE ARE AFFECTED?

The Alzheimer’s Society reports there are more than 850,000 people living with dementia in the UK today, of which more than 500,000 have Alzheimer’s.

It is estimated that the number of people living with dementia in the UK by 2025 will rise to over 1 million.

In the US, it’s estimated there are 5.5 million Alzheimer’s sufferers. A similar percentage rise is expected in the coming years.

As a person’s age increases, so does the risk of them developing dementia.

Rates of diagnosis are improving but many people with dementia are thought to still be undiagnosed.

IS THERE A CURE?

Currently there is no cure for dementia.

But new drugs can slow down its progression and the earlier it is spotted the more effective treatments are.

Source: Alzheimer’s Society

Source: Read Full Article