When you sit at a campfire and look up at the stars, even the tiniest pinpricks of light that you see are massive furnaces, producing intense heat. But hidden among these infernal embers are celestial bodies so dim that they’re invisible to the naked eye.

One such star, a brown dwarf smaller than Jupiter, recently became the coldest star ever to be detected with a radio telescope. At a paltry 797 degrees Fahrenheit, it’s cooler than the average campfire: an ideal star for roasting marshmallows. Don’t forget the graham crackers and chocolate.

A big star like our sun, said Kovi Rose, a doctoral candidate in astronomy at the University of Sydney, is a “nuclear fusion machine that’s working perfectly in space and compressing hydrogen gas and fusing that into helium.” That produces energy that radiates from the star, most noticeable to us in the form of heat and light.

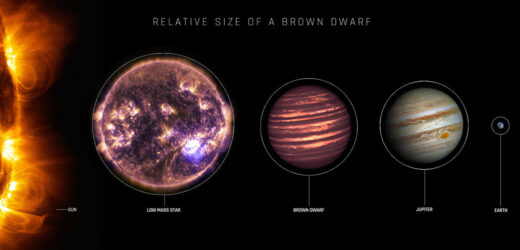

Brown dwarfs, sometimes called “failed stars,” are too small to attain the powerful gravity required to compress hydrogen to the point of nuclear fusion. Instead, “a brown dwarf is partway, in mass and temperature, between a star and a planet,” said Tara Murphy, an astronomy professor at the University of Sydney and a co-author with Mr. Rose of a paper published on Thursday in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. The existence of brown dwarfs was hypothesized 60 years ago, but “they were very hard to find, because they’re not very bright,” Dr. Murphy said.

While brown dwarfs don’t give off much visible light, they do emit energy at other frequencies, which different kinds of telescopes can detect. In 2011, scientists at the California Institute of Technology used infrared telescopes to discover a number of brown dwarfs, including one they named T8 Dwarf WISE J062309.94−045624.6.

Even though the star had been identified based on its infrared emissions, there’s still a wealth of information to be yielded by the other energy it gives off.

“Every band of that electromagnetic spectrum gives you a completely different window into the universe,” Dr. Murphy said. “It’s like a detective story.” The radio waves that Dr. Murphy and Mr. Rose study reveal information about stars’ magnetic fields. (Despite their name, radio waves don’t emit sound.)

As part of Mr. Rose’s Ph.D. thesis, he sifted through radio-wave data generated by the Australian Square Kilometer Array Pathfinder. “Each time that I found something that was able to be cross-matched to the coordinates in the sky of a known star, it was really exciting and really interesting,” he said.

It was surprising to discover, the researchers said, that one of the sources of radio waves was none other than the brown dwarf T8 Dwarf WISE J062309.94−045624.6, in part because fewer than 10 percent of brown dwarfs emit radio waves.

“Once we realized that it was a brown dwarf, yeah, it was definitely quite exciting, because then you kind of go down this rabbit hole of trying to figure out what the implications are, and what we can learn about the magnetic field properties,” Mr. Rose said.

The researchers confirmed their findings with other radio telescopes, including MeerKAT in South Africa and the Australia Telescope Compact Array. While not the coldest star ever discovered (that was WISE J085510.83-071442.5, with a temperature between 54 and 9 degrees Fahrenheit), it is the coldest star ever observed emitting radio waves.

Elena Manjavacas, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore who was not involved with the study, said the findings were “very cool.” Combining the results with those from other kinds of telescopes “gives you a complete picture of basically the 3-D structure of the brown dwarf.”

Beyond the scientific implications of the discovery, Mr. Rose emphasized the bigger picture.

Being out in nature, looking out at the expanse of twinkling lights and knowing that, “in some cases, they’re cooler than the smoke that’s rising off our campfire — I mean, that’s inspiring. It’s inspiring and humbling to understand our place in the universe,” he said.

Source: Read Full Article