The fate of the world’s biggest ice sheet is in our hands: East Antarctic Ice Sheet will cause global sea levels to rise by up to 16 FEET by 2500 if temperatures continue to increase at current rate, study warns

- Melting of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet may result in huge sea level rises by 2050

- Researchers modelled the effects different global temperatures could have on it

- If there is no change in the rate of warming, sea levels could rise by 16 feet

- This could be limited if we reach emissions targets set in the Paris Agreement

An ice sheet that holds about 80 per cent of the world’s glacier ice has the potential to cause global sea levels to rise by up to 16 feet (five metres) by 2500.

Scientists have predicted that melting of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet (EAIS) will result in this increase if temperatures continue to rise at the current rate.

This warming of about 0.32°F (0.18°C) per decade is the result of humanity’s increase in greenhouse gas emissions since the Industrial Revolution.

Researchers from Durham University modelled the effects different temperatures and levels of emissions would have on the ice sheet in the next few centuries.

If no change is made to slow the warming, the EAIS could contribute up to ten feet (three metres) to global sea levels by 2300.

The melting could be limited significantly if emissions targets are met that see global temperature rise limited to 3.6°F (2°C) above pre-industrial levels.

The EAIS could then only contribute about 0.8 inches (two centimetres) of sea level rise by 2100, and 1.6 feet (0.5 metres) by 2500.

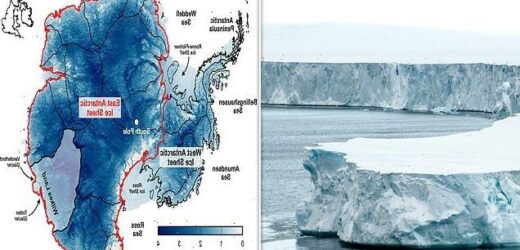

Thickness of ice in Antarctica, showing the location of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet (red outline), which holds the equivalent of 52 metres of sea level rise (alongside the UK and Ireland at the same scale). Wilkes Land (highlighted) has been referred to as East Antarctica’s ‘weak underbelly’, where some glaciers appear to be thinning, retreating and losing mass due to warm ocean currents

Scientists have predicted that melting of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet (EAIS) will result in this increase if temperatures continue to rise at the current rate. Pictured: Ice cliff at the terminus of Vanderford Glacier, Wilkes Land, East Antarctica

WHY IS CURRENT GLOBAL WARMING DIFFERENT TO HOTTER PERIODS IN HISTORY?

Previous periods of warming, that are similar to what the Earth is experiencing today, occurred over hundreds of thousands of years.

About 300,000 years ago, during the mid-Pliocene, temperatures were only between 1.3°F and 3.6°F (2°C and 4°C) higher than present.

This period of warming occurred gradually over 300,000 years and is thought to have been caused by changes in the way the Earth orbits the sun.

However, evidence of today’s global warming indicates it just under 200 years ago.

The Earth’s average surface temperature has increased rapidly by about 1.8°F (1.0°C) since the late 1800s.

This can be explained by the increase in our greenhouse gas emissions since the industrial revolution.

Lead author Professor Chris Stokes said: ‘We used to think East Antarctica was much less vulnerable to climate change, compared to the ice sheets in West Antarctica or Greenland, but we now know there are some areas of East Antarctica that are already showing signs of ice loss.

‘Satellite observations have revealed evidence of thinning and retreating, especially where glaciers draining the main ice sheet come into contact with warm ocean currents.

‘This ice sheet is by far the largest on the planet, containing the equivalent of 52 metres of sea level and it’s really important that we do not awaken this sleeping giant.’

Ice sheets in Greenland and West Antarctica were already predicted to lose ice in the centuries to come.

Greenland is far away from the North Pole so is exposed to warm air, and West Antarctica is affected by warm ocean currents as it sits below sea level.

However the EAIS is home to the staggeringly cold South Pole, and it is located on land that shields it from the sea’s warmth, so it was widely assumed to be more solid.

But in 2020, evidence was found that a part of the EAIS retreated 435 miles (700 km) inland just 400,000 years ago – not that long ago on geological timescales.

This was in response to only 1.8-3.6°F (1-2°C) of warming.

In the study, published today in Nature, researchers from the UK, Australia, France and the USA examined how the EAIS responded to periods of warmth and high carbon dioxide concentrations in the past.

Around three million years ago, during the mid-Pliocene, temperatures were only between 3.6°F and 7.2°F (2°C and 4°C) higher than present.

This range of temperature change is one we could experience later this century.

However, global sea levels in the mid-Pliocene were between 33 and 82 feet (10 and 25 metres) higher than they are now.

Evidence from sea-floor sediments around East Antarctica indicates that part of the ice sheet collapsed and contributed several metres to this.

Carbon dioxide concentrations in that period also only slightly exceeded the current value of 417 parts per million.

This period of warming occurred over a very long timescale – about 300,000 years according to NASA – and is thought to have been caused by changes in the way the Earth orbits the sun.

However current global warming has only been felt for the last few decades, which can only be explained by greenhouse gas emissions from human activity.

Next, the team analysed computer simulations made by previous studies to examine what effects different levels of emissions and temperatures would have on the ice sheet.

If warming continues at its current rate, sustained by high greenhouse gas emissions, the EAIS could contribute nearly half a metre to sea levels by 2100.

Additionally, if it continues beyond 2100, it could contribute around three to ten feet (one to three metres) to global sea levels by 2300, and 7 to 16 feet (two to five metres) by 2500.

This would add to the substantial contributions from Greenland and West Antarctica and thermal expansion of the ocean, threatening millions of people worldwide who live in coastal areas.

In 2020, evidence was found that a part of the EAIS retreated 435 miles (700 km) inland just 400,000 years ago – not that long ago on geological timescales. This finding suggested it was at risk to retreating further as a result of current climate change. Pictured: Scientists drilling a shallow ice core at the surface of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet

Professor Nerilie Abram, from the Australian National University, said: ‘We now have a very small window of opportunity to rapidly lower our greenhouse gas emissions, limit the rise in global temperatures and preserve the East Antarctic Ice Sheet

However, in 2015 new targets were agreed upon by world leaders that attended the UN Climate Change Conference in Paris.

They agreed to limit global warming to well below 3.6°F (2°C) and pursue efforts to limit the rise to 2.7°F (1.5°C) by reducing their countries’ greenhouse gas emissions.

The international researchers found that, if these targets are met, the worst effects of global warming on the world’s largest ice sheet could be avoided.

The EAIS might be thus expected to contribute only about 0.8 inches (two centimetres) of sea level rise by 2100 and 1.6 feet (0.5 metres) by 2500.

Some research shows that snowfall has increased over East Antarctica in the last few decades and, if this continues, it will offset some of the expected ice losses over the next century.

However the researchers say sea levels will still rise due to unstoppable ice losses from Greenland or West Antarctica.

If the Paris Agreement targets for global temperature increase are met, the worst effects on the world’s largest ice sheet could be avoided. The EAIS might be thus expected to contribute only about 0.8 inches (two centimetres) of sea level rise by 2100 and 1.6 feet (0.5 metres) by 2500. Pictured: Iceberg towers from the East Antarctic Ice Sheet

Professor Nerilie Abram, a co-author of the study from the Australian National University in Canberra, said: ‘A key lesson from the past is that the East Antarctic Ice Sheet is highly sensitive to even relatively modest warming scenarios. It isn’t as stable and protected as we once thought.

‘We now have a very small window of opportunity to rapidly lower our greenhouse gas emissions, limit the rise in global temperatures and preserve the East Antarctic Ice Sheet.

‘Taking such action would not only protect the East Antarctic Ice Sheet, but also slow the melting of other major ice sheets such as Greenland and West Antarctica, which are more vulnerable and at higher risk.

‘Therefore, it’s vitally important that countries achieve and strengthen their commitments to the Paris Agreement.’

Professor Stokes added: ‘A key conclusion from our analysis is that the fate of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet remains very much in our hands.’

Startling satellite images show ‘spike melt’ of ice in Greenland over three days

Greenland experienced a ‘spike melt’ from July 15 through 17, which saw its massive ice sheet lose enough water to fill 7.2 million Olympic-sized swimming pools.

The dramatic event was captured in a satellite image that reveals how 18 billion tons of runoff water completely changes the landscape.

The European Union’s Copernicus satellite captured the the climate change-induced melt that shows areas of blue water flowing along the bedrock surface.

It was due to a heatwave gripping the country that enveloped the area in a steady 60 degrees when temperatures are typically no more than 50 degrees around this time of year, according to CNN that first reported on the matter.

Although there have been numerous melts in previous years, the recent one is two times the larger than normal and experts warn it has greatly contributed to an increase in the global sea level.

Read more here

Greenland’s dramatic melt that took place on July 15-17 was captured in a satellite image. The shades of blue are actually melted ice that is making its way through the bedrock surface and out to sea

Source: Read Full Article