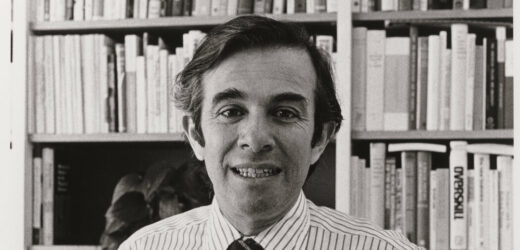

Everett I. Mendelsohn, a longtime Harvard professor who as a scholar of the history of science explored how the evolution of science has been influenced by historical and cultural trends and vice versa, died on June 6 at his home in Cambridge, Mass. He was 91.

His wife, Mary B. Anderson, said the cause was a stroke.

Professor Mendelson’s long association with Harvard began in 1953, when he was a graduate student in biology, and continued for more than half a century. In 1960 he earned a Ph.D. in the history of science at the university, and after a year as a junior fellow, he began teaching. He retired in 2007.

Over that time he became known for lecturing on a diverse array of topics — genetic engineering, the environment, the making of the atomic bomb — and encouraging students to examine how science had influenced world events and everyday lives.

“Everett was one of a new generation of social historians of science who insisted that it was not enough to pay attention to the internal intellectual story of science,” Anne Harrington, the Franklin L. Ford professor of the history of science at Harvard, said by email. “The field needed to attend also to how science was shaped by and also helped shape the conditions of the social world.”

“There was a strong ethical dimension to that work, at least for Everett,” Professor Harrington added. “For years, he taught a course to undergraduates called simply ‘Science and Its Social Problems.’ Using historical methods to bring into focus some of the ethical challenges and ambiguities of science seems today like an obvious move to make; it was not obvious at the time.”

Professor Mendelsohn had a particular interest in the relationship between science and warfare and, as a lifelong pacifist, was active in groups like the American Friends Service Committee and the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s Committee on Science, Arms Control and National Security (of which he was a founder). In February 1968, shortly after returning from a monthlong trip to Cambodia, Thailand and South Vietnam during the Vietnam War, he painted a bleak view of the military situation that was at odds with the official American government line.

“I think we are taking a very bad shellacking militarily,” he told The Boston Globe, “to the extent that every one of the defenses were pierced, from one end of the country to the other.”

In an extensive interview with The Harvard Crimson that same month, he also described the toll the war was taking on civilians, something he saw during a visit to a hospital in Quang Ngai.

“When we went beyond the medical ward into the severe injury ward, you saw the full horror of the war itself,” he said.

A group of physicians dispatched to South Vietnam the previous year by President Lyndon B. Johnson had reported finding only a few cases of civilians burned by napalm (“A greater number of burns appeared to be caused by the careless use of gasoline in stoves,” the group’s report said). But Professor Mendelsohn said he saw dozens of napalm victims at the hospital.

More recently, Professor Mendelsohn had devoted attention to encouraging dialogue that might lead to lasting peace in the Middle East. His family, in a prepared obituary, said that he considered the dearth of progress on that front “his greatest life failure.”

Everett Irwin Mendelsohn was born on Oct. 28, 1931, in New York and raised in the Bronx. His father, Morris, was a salesman for a company that imported candy from Europe, and his mother, May (Albert) Mendelsohn, was a secretary in the New York City public school system.

After graduating from Brooklyn Technical High School in 1949, Professor Mendelsohn studied both biology and history at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, earning a Bachelor of Science degree in 1953.

In 1955, while doing graduate work at Harvard, he studied for a time at the Marine Biological Laboratory at Woods Hole, Mass., where he worked under the biologist Clifford Grobstein on a project that involved extracting hormones from the eye stalks of lobsters. That procedure left the lobster alive and well, and also edible.

“I had lots of friends,” Professor Mendelsohn said in a 2013 video interview for an archive devoted the history of the laboratory, “because they all wanted to come while we had to get rid of the lobsters, which meant cooking them on the beach.”

In 1968, Professor Mendelsohn founded the Journal of the History of Biology.

“Biology, in particular, must be studied in terms of its relationships with the other sciences and with the intellectual currents of its day,” he wrote in an introductory essay in the journal’s first issue. “It may be examined as well for its interaction with the institutions of the society which spawns it.”

Whichever branch of science he was writing or lecturing about, he was concerned with making sure the subject was not arcane.

He told doctoral students that they should be able to go out to Harvard Square and explain their dissertations to people on the street. In a 2013 lecture at Dartmouth College, he talked about the scientific revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries, the Industrial Revolution and the recent digital and biological revolutions, and ended by wondering if advances were in danger of becoming so complex that the general public would not be able to understand them or make informed decisions about their applications — a prospect he did not welcome.

“Scientific revolutions require more fully developed citizen participation, something which is hard, because the knowledge level might be high, and one of the challenges is how you bridge that gap,” he said.

He added, “Science, I guess we could say, in some ways, is certainly too important in our lives to be left to experts alone.”

Professor Mendelsohn’s marriage in 1954 to Mary Maule Leeds ended in divorce. He and Dr. Anderson, an economist and author, married in 1974. In addition to her, he is survived by a sister, Bernice Bronson; three children from his first marriage, Daniel, Sarah and Joanna Mendelsohn; Dr. Anderson’s son from a previous marriage, Marshall Wallace; six grandchildren; and three great-grandchildren.

“In the classroom,” Professor Harrington said, “Everett had a gift of gathering together the threads of a discussion, tidying up any incoherences and distilling the deeper insights. ‘Let me see if I can pull together what I am hearing here,’ he would say. Then he would show students an elevated and elegantly synthesized version of their contributions, so that they would all find themselves amazed and impressed by their own collective thoughtfulness.”

Neil Genzlinger is a writer for the Obituaries desk. Previously he was a television, film and theater critic. More about Neil Genzlinger

Source: Read Full Article