In 1978, James R. Flynn, a political philosopher at the University of Otago, in New Zealand, was writing a book about what constituted a “humane” society. He considered “inhumane” societies as well — dictatorships, apartheid states — and, in his reading, came across the work of Arthur R. Jensen, a psychologist at the University of California at Berkeley.

Dr. Jensen was best known for an article he published in 1969 claiming that the differences between Black and white Americans on I.Q. tests resulted from genetic differences between the races — and that programs that tried to improve Black educational outcomes, like Head Start, were bound to fail.

Dr. Flynn, a committed leftist who had once been a civil rights organizer in Kentucky, felt instinctively that Dr. Jensen was wrong, and he set out to prove it. In 1980 he published a thorough, devastating critique of Dr. Jensen’s work — showing, for example, that many groups of whites scored as low as Black Americans. But he didn’t stop there.

Like most researchers in his field, Dr. Jensen had assumed that intelligence was constant across generations, pointing to the relative stability of I.Q. tests over time as evidence. But Dr. Flynn noticed something that no one else had: Those tests were recalibrated every decade or so. When he looked at the raw, uncalibrated data over nearly 100 years, he found that I.Q. scores had gone up, dramatically.

“If you scored people 100 years ago against our norms, they would score a 70,” or borderline mentally disabled, he said later. “If you scored us against their norms, we would score 130” — borderline gifted.

Just as groundbreaking was his explanation for why. The rise was too fast to be genetic, nor could it be that our recent ancestors were less intelligent than we are. Rather, he argued, the last century has seen a revolution in abstract thinking, what he called “scientific spectacles,” brought on by the demands of a technologically robust industrial society. This new order, he maintained, required greater educational attainment and an ability to think in terms of symbols, analogies and complex logic — exactly what many I.Q. tests measure.

“He surprised everyone, despite the fact that the field of intelligence research is intensely data centric,” the Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker said in an interview. “This philosopher discovered a major phenomenon that everyone had missed.”

Though Dr. Flynn published his research in 1984, it was not until a decade later that it drew attention outside the narrow world of intelligence researchers. The turning point came with the publication in 1994 of “The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life,” by Richard J. Herrnstein and Charles A. Murray, in which they argued that genes play a dominant role in shaping intelligence, a position that its fiercest critics called racist. In reviewing arguments for and against their position, the authors outlined Dr. Flynn’s research and even gave it a name: the Flynn effect.

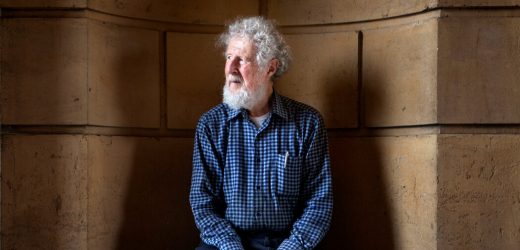

A buzzword was born. The Flynn effect became shorthand for an optimistic view of the human condition and made Dr. Flynn something of a pop-culture hero, an image underscored by his lanky build, rumpled outfits and Einsteinian mess of curly white hair. A 2013 TED Talk in which he explains “why our I.Q. levels are higher than our grandparents’” has been viewed 4.4 million times.

Dr. Flynn died at 86 on Dec. 11 at an assisted living center in Dunedin, New Zealand. The cause was intestinal cancer, said his son, Victor Flynn, a math professor at Oxford.

In addition to his son, he is survived by his wife, Emily (Malkin) Flynn, a divorce lawyer, and his daughter, Natalie Flynn, a clinical psychologist.

Dr. Flynn and Dr. Murray became frequent debating partners, especially after Dr. Flynn showed in subsequent research, with William T. Dickens, that the Black-white I.Q. gap had diminished significantly between 1972 and 2002.

But while they differed intellectually, Dr. Flynn was also quick to defend Dr. Murray — and Dr. Jensen, for that matter — against the racism accusations. He dedicated one of his books to Dr. Jensen, and he took Dr. Murray’s side in 2017 after students at Middlebury shut down a speech by Dr. Murray.

“Jim was a paragon of intellectual curiosity and willingness to look at all the evidence,” Dr. Murray said in an interview. “He had almost a childlike curiosity, and I mean that in a good way.”

James Robert Flynn was born on April 28, 1934, in Washington. His father, Joseph Flynn, was a journalist, and his mother, Mae Flynn, was a homemaker.

Raised a Roman Catholic, Mr. Flynn renounced religion when he was 12. As a scholarship student at the University of Chicago, he had originally planned to study mathematics or physics, but he was nagged by the question of how morality functions without faith. Having completed all his core requirements in his freshman year, he dived into political philosophy, receiving his doctorate in 1958, when he was just 24.

Already a man of the left — Dr. Flynn joined the Socialist Party in college — after graduating he became involved in the civil rights movement. He met Emily Malkin at a protest against a segregated amusement park in the Washington suburbs, and they named their first child after Dr. Flynn’s hero, the American socialist Eugene Victor Debs.

He continued his activism as a professor at what is now Eastern Kentucky University, in the town of Richmond, about 30 miles south of Lexington. There he helped organize against the city’s segregated downtown businesses, drawing threats from the mayor and a reprimand from the college president. A lifelong competitive runner, he was removed as the track coach.

He left in 1961 for a job at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, then another at Lake Forest College, outside Chicago. But he came to believe that his left-wing politics had foreclosed the possibility of an academic career in the United States. He looked abroad, and in 1963 landed a job at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand. Four years later he moved to the University of Otago, in Dunedin, where he remained until his retirement in 2020.

Though Dr. Flynn was based in the university’s political studies department, his writings and interests ranged widely. In between books on liberalism, world history and political censorship, he advised Australia’s prime minister on foreign policy, organized against the war in Vietnam and, in the 1990s, founded two left-wing political parties. He ran unsuccessfully for Parliament three times.

Though he was widely recognized for making one of the most significant psychological discoveries of the late 20th century, Dr. Flynn was modest about his contributions, as well as his standing in his adopted field. He had, he said, merely taken a “holiday” in psychology, then stuck around out of a sense of obligation to clean up the “mess” he had made.

He was always careful to qualify his claims: Despite his success in overturning the notion that genes are everything, he never dismissed it entirely. Genes played a large part in determining intelligence, he maintained, especially at the individual level, but so did environment and what he called “chance factors,” like accidents and life decisions — in other words, free will. And environment made all the difference in explaining the gaps between different groups within a society, whether racial, gender, class or otherwise.

He was also aware of the uncomfortable implications of his position: that by ascribing differences between Black and white I.Q. tests to environment, he was running the risk of blaming Black parenting and culture.

“You’re caught between the devil and the deep blue sea,” he said in an interview with Skeptic magazine. “Either you say it’s genetic or you say there is something about Black child rearing practices that don’t provide cognitive challenge, in which case you’re blaming the victim.”

Unlike many academics, Dr. Flynn increased his output as he aged: Eleven of his 18 books appeared in his last decade, many of them going back to his earlier interests in political theory and free speech. He became increasingly focused on academic freedom and a critic of so-called cancel culture, especially on campus.

His last book, “In Defense of Free Speech: The University as Censor,” was rejected by its first publisher as incendiary — though, as Dr. Flynn pointed out, he was merely summarizing the positions of people he disagreed with, in order to make a larger point. Frustrated, he found a new publisher for the book, which he retitled “A Book Too Risky to Publish: Free Speech and Universities” (2019).

“Dad was always very respectful of people he disagreed with, and hated the trend of boycotting academics because of their views,” his son, Professor Flynn, said. “He very much thought that people should be able to express their views and if you don’t agree, argue with them.”

Source: Read Full Article