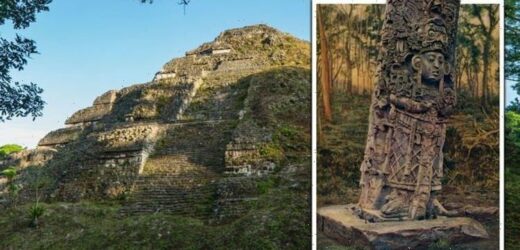

Tikal: Shocking discoveries made at Ancient Mayan City

We use your sign-up to provide content in ways you’ve consented to and to improve our understanding of you. This may include adverts from us and 3rd parties based on our understanding. You can unsubscribe at any time. More info

The Maya civilisation has fascinated historians and archaeologists for years. John Lloyd Stephens, an American traveller and archaeologist, is largely regarded as having been the first Western person to discover the lost civilisation between 1839 and 1842. The Maya still live today in Central America, but they number nowhere near the same as during the peak of their ancestors’ ancient empire — with estimates suggesting they were up to 20 million strong.

Centuries before the birth of Christ, the Maya were a rural civilisation, relying on corn as a staple part of their diet.

To successfully grow corn and other crops they were required to mark the changing seasons.

This was particularly challenging given the tropical climate of Central America, where daylight varies little between summer and winter.

The method in which they kept the time was explored during the Smithsonian Channel’s documentary, ‘Sacred site: Maya’.

Here, work in the ancient city of Tikal, Guatemala, one of the Maya’s oldest sites, was examined.

Around 600 BC, the Maya started work on a complex of buildings almost covered by dense jungle within the city, known today as Mundo Perdido — the Lost World.

For the Maya, the buildings served a visible and vital purpose.

Several times a year, they climbed the Mundo Perdido’s central pyramid to observe the sky to the east.

JUST IN: NASA will test ‘planetary defence’ to stop future asteroid impacts

From this vantage point, they could see three small structures, known today as E1, E2, and E3.

Viewed from the pyramid during the summer solstice, the sun ascends from behind structure, E1; during the equinoxes it rises from behind the central pyramid, E2; and during the winter solstice it emerges from behind E3.

For the Maya, the winter solstice was characterised by a period of dryness, while the summer solstice welcomed heavy rain.

The documentary’s said: “Sites like Mundo Perdido give accurate knowledge of when a dry or rainy period is at hand.

DON’T MISS

Putin set to deliver ‘straw that broke camel’s back’ to Brussels [REPORT]

Ukraine energy boss hands UK ‘easy’ solution to EU gas crisis [INSIGHT]

Scientists send dire ocean tide warning as Moon is slowly ‘leaving us’ [ANALYSIS]

“For the Maya, using astronomy to mark the seasons is not an agricultural technique — it is the essence of religion.”

While the ancient civilisation would be aware that the weather was directly influencing their crops, they appear to have viewed the cause of the weather as an act of the gods, according to research.

The way in which they tracked the weather, then, might be viewed as akin to worship.

Tikal has offered archaeologists countless more relics and information about the Maya.

In 2017, “groundbreaking technology” revealed something astonishing about Tikal: that the buildings on show were but a small part of the city.

Also explored in the documentary, the narrator noted: “In its heyday, the city was far larger than what is now visible.

“Remote sensing technology has shown that Tikal was once part of a much greater collection of cities now hidden beneath the green roof of the jungle.”

The sheer extent of Tikal and its population is beyond anything previously imagined: it was a centre of trade and industry, with over 100,000 living people in close quarters.

These inhabitants ranged from labourers and servants, architects and traders, all the way up to the upper echelons of Maya civilisation.

Tikal had its own King or Queen who would have communed with the gods on behalf of the people.

Somewhere between the eighth and ninth centuries, the Maya disappeared in their droves.

Many theories have attempted to explain why they left the lands, including overpopulation, environmental degradation, warfare, shifting trade routes and extended drought.

Source: Read Full Article