Center for Astrophysics on 'first potential planet' outside galaxy

We use your sign-up to provide content in ways you’ve consented to and to improve our understanding of you. This may include adverts from us and 3rd parties based on our understanding. You can unsubscribe at any time. More info

The tantalising discovery was made more than 28 million light-years away in the spiral galaxy M51 (Messier 51). The findings were published on Monday in the journal Nature Astronomy. Until now, astronomers have only been able to detect so-called exoplanets within our home galaxy.

Exoplanets are described as alien worlds that orbit stars far beyond our solar system.

Almost all of these planets have been found within 3,000 light-years from Earth.

The newest discovery, if confirmed, will open up the doors for scientists to hunt down exoplanets at previously unimaginable distances.

Rosanne Di Stefano of the Center for Astrophysics – Harvard and Smithsonian (CfA) in Cambridge, said: “We are trying to open up a whole new arena for finding other worlds by searching for planet candidates at X-ray wavelengths, a strategy that makes it possible to discover them in other galaxies.”

According to figures published by NASA, astronomers have so far only found and confirmed more than 4,000 exoplanets in our galactic neighbourhood.

In a universe with a potentially infinite number of galaxies and planets, this might seem trivial.

However, the first ever exoplanet was only confirmed in 1992 and technological advancements have come a long way since.

The best way to search for exoplanets, as was the case in the latest discovery, is to look for their transits.

When a planet or some other object passes in front of a star, powerful space telescopes may be able to detect a minute dip in their brightness.

NASA’s TESS and Kepler telescopes have used this technique to great success, but there are some limitations.

Space: Stunning time-lapse reveals 4,000 exoplanets

For instance, the transiting planet needs to pass at an angle that will be visible from Earth.

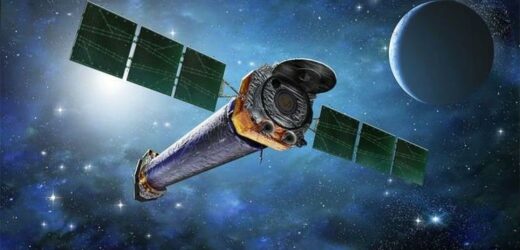

Dr Di Stefano and colleagues adapted the transit technique NASA’s Chandra telescope and instead of brightness, recorded dips in the X-rays received from so-called X-ray binaries.

These are systems where a neutron star or black hole is siphoning the gas of a nearby companion star.

In this particular case, the astronomers have named the binary system M51-ULS-1.

As the material gets sucked in, it is superheated and emits large amounts of X-ray radiation.

This region that emits the X-rays is fairly small and a planet passing in front of it has the potential to block most if not all of it.

This possibility could make revolutionise the way astronomers look for planets outside of the Milky Way.

However, more data needs to be collected before M51-ULS-1 discovery is confirmed.

And unfortunately, the candidate planet will not make another transit for some 70 years due to its lengthy orbit.

Study co-author Nia Imara of the University of California at Santa Cruz said: “Unfortunately to confirm that we’re seeing a planet we would likely have to wait decades to see another transit.

“And because of the uncertainties about how long it takes to orbit, we wouldn’t know exactly when to look.”

Julia Berndtsson of Princeton University in New Jersey added: “We know we are making an exciting and bold claim so we expect that other astronomers will look at it very carefully.

“We think we have a strong argument, and this process is how science works.”

A possible explanation that would eliminate an exoplanet discovery, is the passing of gas and dust in front of the X-ray source.

However, the data so far is more consistent with the presence of a planet.

Source: Read Full Article