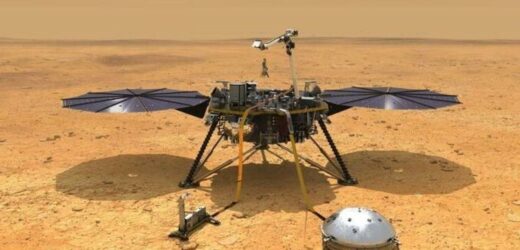

NASA launch Mars Insight Lander 'WALL-E' and 'EVA'

We use your sign-up to provide content in ways you’ve consented to and to improve our understanding of you. This may include adverts from us and 3rd parties based on our understanding. You can unsubscribe at any time. More info

The marsquakes — the martian equivalent of earthquakes — were detected beneath the Cerberus Fossae, a series of semi-parallel fissures formed by tectonic activity. This area, which is less than 20 million years old, lies under Cerberus, a region named after the mythical Greek hound of Hades, which appears from space as a dark spot on the surface of the Red Planet. Seismic activity was first detected beneath Cerberus Fossae back in 2019 — although researchers attributed this to the build-up of tectonic stresses along geological faults.

In the new study, geophysicists Professor Hrvoje Tkalčić of the Australian National University and Professor Weijia Sun of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing studied data collected by the seismometer attached to NASA’s InSight lander, which has been recording tremors on the Red Planet since 2018.

Using a special algorithm, the duo were able to reveal 47 marsquakes centred beneath Cerberus Fossae — occurring within a period of 350 Martian days, the equivalent of roughly 359 days here on Earth — that were previously hidden within the seismic data.

Prof. Tkalčić said: “We found that these marsquakes repeatedly occurred at all times of the Martian day, whereas marsquakes detected and reported by NASA in the past appeared to have occurred only during the dead of night when the planet is quieter

The occurrence of the quakes throughout all times of the day also allowed them to rule out tidal effects generated by Mars’ moons.

Given this, Prof. Tkalčić added, “we can assume that the movement of molten rock in the Martian mantle is the trigger for these 47 newly detected marsquakes beneath the Cerberus Fossae region.”

According to the team, the marsquakes were relatively small in magnitude — and, had they occurred on Earth, would have likely been barely felt.

Prof. Tkalčić said: “Knowing that the Martian mantle is still active is crucial to our understanding of how Mars evolved as a planet.

“It can help us answer fundamental questions about the solar system and the state of Mars’ core, mantle, and the evolution of its currently-lacking magnetic field.”

Mars is thought to have once had a magnetic field just like the one found on Earth — which respectively were and are caused by the motion of molten metals within each planet’s core.

This would have shielded the planet’s atmosphere from space weather — allowing it to support liquid water on its surface and, some experts have speculated, perhaps even life.

However, Mars’ magnetic field was lost some 3.7 billion years ago — leaving most of the red planet’s atmosphere to be blasted away by the solar wind.

It had long been assumed that Mars’ heart had cooled such that it was no longer capable of supporting the kind of internal motions needed to generate a magnetic field.

DON’T MISS:

Germany backs down and REFUSES to cut energy ties with Russia [INSIGHT]

Covid may cause brain damage even with only mild respiratory symptoms [ANALYSIS]

Russia unleashes fury in space and threatens to abandon ISS again [REPORT]

Prof. Tkalčić added: “The marsquakes indirectly help us understand whether convection is occurring inside of the planet’s interior […] which it looks like it is based on our findings.”

Given this, he said, “there must be another mechanism at play that is preventing a magnetic field from developing on Mars.”

“All life on Earth is possible because of the Earth’s magnetic field and its ability to shield us from cosmic radiation, so without a magnetic field life as we know it simply wouldn’t be possible.

“Understanding Mars’ magnetic field, how it evolved, and at which stage of the planet’s history it stopped is obviously important for future missions and is critical if scientists one day hope to establish human life on Mars.”

The full findings of the study were published in the journal Nature Communications.

Source: Read Full Article