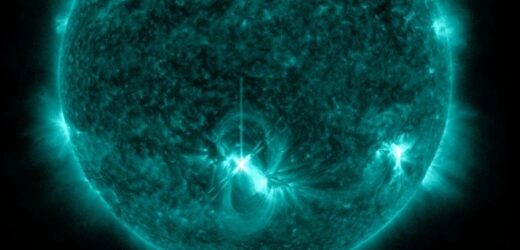

NASA Solar Observatory captures solar flares in October

We use your sign-up to provide content in ways you’ve consented to and to improve our understanding of you. This may include adverts from us and 3rd parties based on our understanding. You can unsubscribe at any time. More info

NASA said: “Solar flares are powerful bursts of radiation. Harmful radiation from a flare cannot pass through Earth’s atmosphere to physically affect humans on the ground. However — when intense enough — they can disturb the atmosphere in the layer where GPS and communications signals travel.”

Yesterday’s solar spectacle, which peaked at 4:35 pm BST, releasing an extreme ultraviolet flash, has been classified by NASA experts as an X1.5-class flare.

Flares are grouped into five categories — A, B, C, M and then X, the strongest — and then given a number denoting the size of the phenomena.

Originating from a sunspot dubbed “AR3006”, the flare released radiation that ionized the top of Earth’s atmosphere, causing a blackout in the shortwave radio band around the Atlantic.

Solar flares are triggered by a process called “magnetic reconnection”, in which the geometry of the magnetic field in the Sun’s plasma is altered.

As the magnetic field lines break and reconnect, they release some of their stored energy in the form of heat and kinetic energy.

The Sun tends to follow 11-year cycles, with solar activity in each building to a peak — during which the star’s magnetic poles flip.

This reversal is then followed by a ramping down period before the next cycle begins.

Astronomers began numbering the solar cycles in 1775 — which is when extensive monitoring of solar activity first began — and we are presently in Solar Cycle 25.

Cycle 25 has yet to reach its peak, meaning that increasing levels of solar activity can be expected over the next couple of years until the poles flip in late 2024 or early 2025.

Energy can be released from the Sun in both the form of solar flares — sudden flashes of radiation — and so-called coronal mass ejections, or CMEs.

The latter, one of the most powerful forms of solar storm, manifests as a belched-out cloud of charged particles and electromagnetic fluctuations.

If sufficiently large, CMEs have the potential to wreak havoc on the Earth, inducing fluctuations in the power grid, disrupting high-frequency radio signals and interfering with satellite operations in low-Earth orbit.

According to SpaceWeather.com, a “mish-mash” of CMEs left the Sun’s southern hemisphere after the flare, although it is unclear if the phenomena are related.

Two other events happened on the Sun at the same time that could have been connected to the CME — one was a filament eruption to the right of the X-class flare, the other a C4-class flare to the right.

Experts with the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) are working to determine if any of the CMEs are likely to hit the Earth.

DON’T MISS:

Royal Navy’s new £30bn nuke subs can launch 12 separate missiles [INSIGHT]

Solar storm warning: Earth set for ‘glancing blow’ in HOURS [REPORT]

Putin could drop tactical nuke on Ukraine TOMORROW [ANALYSIS]

The most severe geomagnetic storm on record — the so-called “Carrington Event” — occurred in the wake of CME in the September of 1859.

The Carrington Event affected telegraph systems across both Europe and North America, as well as the recently-lain transatlantic link that connected them.

Currents generated in cables by the space weather event reportedly caused telegraph pylons to spark, operators to receive electric shocks and some lines to fail completely.

Other lines, meanwhile, were found to still operate even once their power had been cut, so strong were the electrical currents induced by the storm.

Fortunately, we are most unlikely to experience a space weather episode on the scale of the Carrington Event in the present solar cycle, which is relatively weak.

Source: Read Full Article