Imagine a bunch of beetles minding their own business on an algae-covered rock. All of a sudden, they get hoovered up whole into the beak of a slim, long-necked dinosaur ancestor. R.I.P. — but on the bright side, through a complex combination of luck and microbial activity, their tiny corpses become frozen in time. And over 200 million years later, scientists uncover them while rooting around in fossilized feces.

These coprolites, as they’re called, can provide extraordinarily detailed insight into long-lost ecosystems, according to new research published in Current Biology. A team of researchers found nearly unscathed beetles, now extinct, that are new to science, suspended inside a piece of excrement from the Triassic Period. The scientists suspect that the waste belonged to Silesaurus opolensis, a close relative of dinosaurs that lived about 230 million years ago, although it is tricky to place once separated from its point of origin.

“We decided to look at coprolites to try to understand who ate whom in this ecosystem,” said the paper’s lead author, Martin Qvarnstrom, a paleontologist at Uppsala University in Sweden. “And in one of the fragments of coprolites, all these beetles popped up.”

The coprolite was collected near the village of Krasiejow in southern Poland, at a quarry where remains of S. opolensis and other Late Triassic vertebrates have been excavated. At the site, recalled Grzegorz Niedzwiedzki, a co-author and also a paleontologist at Uppsala University, few other researchers were interested in the coprolites; many are still just lying there, he said. But the bland-looking structures can act as “miniature sarcophagi” that hold together fragile structures like hair, feathers and, in this case, three-dimensional insects, for hundreds of millions of years.

“We have been discovering over time that coprolites can provide fossil evidence for ancient organisms that are not often otherwise preserved,” said Karen Chin, a paleontologist at the University of Colorado, Boulder, who was not involved in the study.

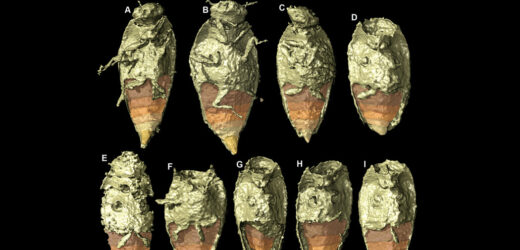

But looking inside coprolites can be difficult, Dr. Qvarnstrom said. So the researchers took this specimen to the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in France to scan its contents and render them in 3-D.

A lot of the hard work comes in combing carefully through the resulting images to tease out what’s what, Dr. Qvarnstrom said. In addition to the beetles, the coprolite contained “small bits and pieces of God knows what, just digested small chunks of something.”

Other researchers were also surprised by the intact beetles found in the specimen.

“I was so blown away by how well these things were preserved,” said Sam Heads, curator of paleontology at the Illinois Natural History Survey, who was not involved in the study.

Dr. Qvarnstrom initially thought the insects must have climbed aboard following defecation. But the researchers saw many different stages of chewed-up-ness, so to speak, from almost fully preserved bodies down to disembodied heads, wings and other parts, many from the same kind of boat-like, millimeter-and-a-half-long beetle.

The researchers determined that the new species and genus, Triamyxa coprolithica, belongs to an extinct and previously unidentified family in a lineage of small beetles, Myxophaga, that today tend to live around algal mats. According to the authors, this is the first insect species described in the fossilized feces of a vertebrate animal.

As for how some beetles made it through the animal’s gut without much damage, Dr. Qvarnstrom thinks there are a few possibilities. The beetles were tiny, and might have been accidentally sucked up en masse while congregating on a piece of algae eaten by a Silesaurus opolensis; they also seem to have been well-defended by their exoskeleton, like modern beetles. The ones who weren’t chewed up still probably died quickly, Dr. Qvarnstrom said. “They didn’t have to suffocate in the poop.”

Beetles are probably the most diverse group of organisms on the planet, and learning more about their early evolution could help researchers understand why that is, said Martin Fikacek, a co-author and entomologist at National Sun Yat-sen University in Taiwan.

The Triassic Period, when this coprolite was produced, is “kind of a black hole when it comes to our understanding of the insect fossil record,” Dr. Heads said. “A beetle of the Triassic age is really a significant discovery.”

Learning more about the diets of these close dinosaur relatives, Dr. Qvarnstrom said, might also help researchers better understand how dinosaurs eventually became so ecologically dominant.

“If we want to know more about the past,” he said, “I think it’s fairly important to get all the pieces of the puzzle.”

Source: Read Full Article