NASA observatory spots flurry of solar flares

We use your sign-up to provide content in ways you’ve consented to and to improve our understanding of you. This may include adverts from us and 3rd parties based on our understanding. You can unsubscribe at any time. More info

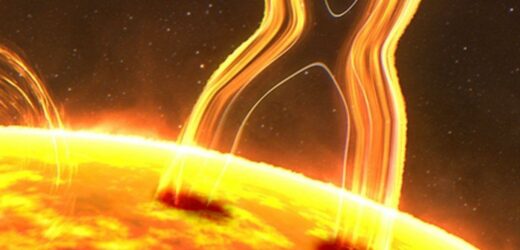

Solar flares, the largest known explosions in the solar system, are triggered by a process called “magnetic reconnection” that occurs in plasma. Plasma is a form of superheated gas so energised its atoms break apart, forming a soup of positively charged ions and negatively charged electrons that is exquisitely sensitive to magnetic fields. Reconnection occurs when the geometry of a magnetic field in plasma is rearranged as a result of field lines getting too close together. To assume a new configuration, field lines break and reconnect — and in doing so release some of the stored energy of the field as heat and kinetic energy, sending particles streaming out along the field lines.

While rare on the Earth, plasma is common out in the universe, and magnetic reconnection is known to occur in assorted locations from around black holes to near-Earth space and on the surface of the Sun.

The type of reconnection that sets off solar flares involves “collisionless” plasmas in which, as the name suggests, the particles are so spread out that they do not collide.

The process is also particularly rapid, and is thus known as “fast reconnection”.

As astrophysicist Dr Barbara Giles of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland explains: “We have known for a while that fast reconnection happens at a certain rate that seems to be pretty constant.

“But what really drives that rate has been a mystery until now.”

In their study, physicist Professor Yi-Hsin Liu of New Hampshire’s Dartmouth College and his colleagues at NASA’s Magnetospheric Multiscale Mission present a theory to explain this consistent reconnection rate — one that relies on a common magnetic phenomenon.

This phenomena, the “Hall Effect”, involves the interaction between magnetic fields and electric currents, and describes how charge carriers in a conductor like plasma can be influenced by the presence of a magnetic field.

The Hall Effect is utilised in such household devices as the sensors that time anti-lock braking systems in vehicles, those that detect when the flip cover of a phone is closed, and even those that allow 3D printers to function.

According to the team, during fast magnetic reconnection, the charged ions and electrons in plasma stop moving as a group and start moving individually.

In their study, physicist Professor Yi-Hsin Liu of New Hampshire’s Dartmouth College and his colleagues at NASA’s Magnetospheric Multiscale Mission present a theory to explain this consistent reconnection rate — one that relies on a common magnetic phenomenon.

This phenomena, the “Hall Effect”, involves the interaction between magnetic fields and electric currents, and describes how charge carriers in a conductor like plasma can be influenced by the presence of a magnetic field.

The Hall Effect is utilised in such household devices as the sensors that time anti-lock braking systems in vehicles, those that detect when the flip cover of a phone is closed, and even those that allow 3D printers to function.

According to the team, during fast magnetic reconnection, the charged ions and electrons in plasma stop moving as a group and start moving individually.

This gives rise to the Hall Effect, creating an unstable energy vacuum at the point of reconnection, which then implodes thanks to the pressure of the magnetic fields and releases immense amounts of energy at a predictable rate.

Prof. Liu, deputy lead of the MMS theory and modelling team, said: “We finally understand what makes this type of magnetic reconnection so fast.

“We now have a theory to explain it fully.”

NASA’s Magnetospheric Multiscale Mission will be testing this theory in the coming years, using their four specially-designed satellites which orbit the Earth in a tetrahedral formation studying reconnection, as it happens, at a higher resolution that would be possible on the Earth.

DON’T MISS:

EU in turmoil as Orban backs Putin with veto on energy ban [REPORT]

Energy crisis: UK opens North Sea taps to SLASH household bills [INSIGHT]

Pandemic horror: Climate change to cause 4000 new virus transmissions [ANALYSIS]

This gives rise to the Hall Effect, creating an unstable energy vacuum at the point of reconnection, which then implodes thanks to the pressure of the magnetic fields and releases immense amounts of energy at a predictable rate.

Prof. Liu, deputy lead of the MMS theory and modelling team, said: “We finally understand what makes this type of magnetic reconnection so fast.

“We now have a theory to explain it fully.”

NASA’s Magnetospheric Multiscale Mission will be testing this theory in the coming years, using their four specially-designed satellites which orbit the Earth in a tetrahedral formation studying reconnection, as it happens, at a higher resolution that would be possible on the Earth.

Dr Giles said: “Ultimately, if we can understand how magnetic reconnection operates, then we can better predict events that can impact us on Earth, like geomagnetic storms and solar flares.”

The energy from solar flares can disrupt transmissions in the upper atmosphere — thereby throwing off, for example, the signals sent from GPS satellites.

The astrophysicist added: “And if we can understand how reconnection is initiated, it will also help energy research because researchers could better control magnetic fields in fusion devices.”

The full findings of the study were published in the journal Communications Physics.

Source: Read Full Article