‘Lost City of Zakhiku’ has RESURFACED! Ruins of a 3,400-year-old settlement that were submerged for decades in Iraq reappear above the surface as reservoir dries up following extreme drought

- Ruins of a 3,400-year-old city have been exposed from the Tigris river in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq

- A drought meant water had to be pulled from the Mosul reservoir for irrigation and lowered water levels

- Archeologists from Germany and Kurdistan rushed to excavate the buildings before they were resubmerged

- They discovered a fortitude with towers and walls, a multi-storey storage building and an industrial complex

- The city is now underwater again, but is covered in plastic sheets and gravel to prevent further degradation

The lost city of ‘Zakhiku’ has resurfaced after spending decades underwater in the Mosul reservoir on the River Tigris in Iraq.

The 3,400-year-old settlement emerged earlier this year, after a months-long period of extreme drought in the country resulted in large amounts of water being drawn from the reservoir to irrigate crops, causing water levels to fall.

This resulted in ancient city buildings becoming exposed, including a huge fortification, a multi-storey storage building and an industrial complex, all dating back 3,400 years to the time of the Empire of Mittani (1550–1350 BC).

A team of German and Kurdish archaeologists first excavated the Mittani Empire-era city during a dry spell in 2018, but were not able to fully investigate before it became submerged underwater again.

So this latest unforeseen dry spell put them under pressure to excavate and document as much of the Bronze Age city as possible, before the water level rose once more.

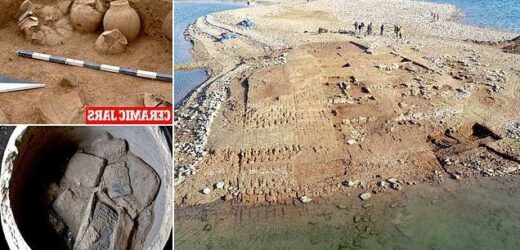

An aerial view of the recent excavations at the Kemune archeological site in the Mosul reservoir, with Bronze Age architecture partially submerged in the lake

Throughout January and February, the researchers mapped out new areas of the city including a huge fortification, a multi-storey storage building and an industrial complex

Large buildings from the Mittani period are being measured and archaeologically documented by archeologists from University of Freiburg and University of Tübingen

Archaeologists and workers uncover the walls of a large building in the old city complex, which is interpreted as a storage building from the time of the Mittani Empire

WHAT DO WE KNOW ABOUT THE ANCIENT CITY?

The 3,400-year-old settlement is located in the archeological site Kemune in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq.

It is thought to be ancient city of Zakhiku, according to a tablet discovered there.

Zakhiku was a capital of the Empire of Mittani, which controlled large parts of northern Mesopotamia and Syria between 1550–1350 BC.

References to this city appear in historic records dating to around 1800 BC, suggesting that it stood in the Tigris River Valley for at least four centuries.

A palace was discovered in the Kemune site in 2018 that had interior walls up to 6.5 feet thick (2 metres) as well as plastered structures and bright painted murals.

It is thought that the building would have stood on an elevated terrace around 66 feet (20 metres) from where the eastern bank of the Tigris river originally was.

A huge fortification, a multi-storey storage building and an industrial complex were also discovered earlier this year.

The extensive ancient metropolis is located in Kemune in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, and once sat on the River Tigris.

Construction of the Mosul dam took place between 1981 and 1984, and the following spring it began to inundate the Tigris river and fill the reservoir.

This submerged many archeological sites in the region, including Kemune.

The city is thought to be the ancient city of Zakhiku, that dates to the time of the Empire of Mittani – approximately 1550–1350 BC – which controlled large parts of northern Mesopotamia and Syria.

The excavation was led by Chairman of the Kurdistan Archaeology Organization, Dr. Hasan Ahmed Qasim, Dr. Ivana Puljiz from the University of Freiburg, and Dr. Peter Pfälzner from the University of Tübingen.

The walls of the fort, some of which stood several metres in height, were extremely well-preserved despite being kept underwater for over 40 years.

The pristine condition of the walls, made from sun-dried mud bricks, is due to the building being covered in a protective coating of rubble during the earthquake that destroyed the city in 1350 BC.

Dr. Puljiz said: ‘The huge magazine building is of particular importance because enormous quantities of goods must have been stored in it, probably brought from all over the region.’

Hasan Qasim added: ‘The excavation results show that the site was an important centre in the Mittani Empire.’

Five ceramic jars were also discovered which contained over 100 cuneiform tablets, dating back to the Middle Assyrian period shortly after the earthquake.

Some clay tablets, which may be letters, were found still in their clay envelopes and are being translated.

The archeologists hope they will provide important information about the end of the Mittani-period city and the beginning of Assyrian rule in the region, including the politics, economy and history.

‘It is close to a miracle that cuneiform tablets made of unfired clay survived so many decades under water,’ Dr. Pfälzner said.

This was all in addition to a palace that had already been documented in 2018, when a severe drought first caused the dam to recede.

The palace had interior walls up to 6.5 feet thick (2 metres) as well as plastered structures and bright painted murals.

Fired bricks used as floor slabs and inscribed clay tablets were also recovered.

It is thought that the palace would have stood on an elevated terrace around 66 feet (20 metres) from where the eastern bank of the Tigris river originally was.

Iraq is one of the countries in the world most affected by climate change, with average temperatures having risen by at least 33.3°F (0.7°C) over the last century.

This has resulted in periods of extreme heat, including a drought that started last December and meant water had to be pulled from the Mosul reservoir to water crops, exposing the city.

Archaeologists and workers uncover walls of buildings in Kemune’s ancient city complex

The mudbricks of the Bronze Age buildings are soaked by the water of the reservoir, but can still be clearly identified and exposed by archeologists

After the research team’s work was completed, the excavation was covered over a large area with plastic sheeting to protect it from the rising water of the Mosul reservoir

Before the water rose again, the excavated buildings were coated in a plastic sheeting before being covered with gravel.

This was to protect the walls of unbaked clay and any other finds still hidden in the ruins during times of flooding from erosion and degradation.

The city is now completely underwater once more, as the water levels in the reservoir have risen back up.

The findings, funded by Fritz Thyssen Foundation and Gerda Henkel Foundation, were announced by the University of Tübingen on Monday.

CLIMATE CHANGE IN IRAQ

Iraq is one of the countries in the world most affected by climate change, with average temperatures having risen by at least 33.3°F (0.7°C) over the last century

The mean annual rainfall is projected to decrease by 9 per cent by 2050, according to the World Bank Group

Sand or dust storms have also increased dramatically in frequency, in large part due to soil degradation.

More than 50 per cent of the water used in Iraq originates in Turkey, Syria and Iran, and water management practices have resulted in less water reaching southern Iraq

The rivers pass through one of the driest areas in the region, and evaporation causes an increase in salinity

These factors combined have undermined Iraq’s agricultural sector, for example its land under cultivation was reduced by half in 2018 due to droughts

Source: ICRC

Cracked earth after a drop of water level at Tigris River in Baghdad, Iraq

Source: Read Full Article