A new form of protective coating against corrosion is capable of both self-repairing and highlighting where holes and cracks have formed, a study has found. Corrosion — a natural process which converts refined metals into more chemically stable oxides — affects all manner of constructions from bridges to skyscrapers and ships to cars. In fact, a whopping 3.5 percent of the world’s annual gross domestic product, or some £3.3trillion each year, is invested in the fight against corrosion.

In their study, chemists led by Professors Markus Niederberger and Walter Caseri of ETH Zürich have developed a special plastic which they say could significantly improve and simplify corrosion protection.

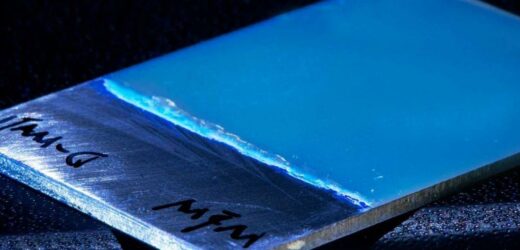

When mixed as a paint and heated, the material — known as poly(phenylene methylene), or PPM for short — can be sprayed directly onto a surface in need of protection from corrosion.

After solidifying, the special polymer actually seals any damage to the coating all by itself, with no need for external intervention.

Prof. Caseri: “Self-repair mechanisms are in great demand, but they’re very difficult to attain, and good solutions are still rare.”

Most existing self-repair solutions rely on additives that migrate within the polymer over time, and can end up being released into the surrounding environment.

PPM, Prof. Caseri adds, “doesn’t require any additives.”

At the end of the life of the coated product or structure, the polymer can be completely removed and then recycled with only around 5 percent loss of material — at which point, it can be applied to protect a different surface.

In fact, in trials, the team was able to recycle PPM up to five times. In contrast, epoxy-based corrosion protection materials can only be used once and typically end up being either incinerated or placed in landfill.

Furthermore, lab tests revealed that not only does PPM protect metals well against corrosion — aluminium in particular — it can be applied in layers that are up to ten times thicker than conventional protective agents like epoxy resins while remaining durable.

According to the team, the origins of PPM were serendipitous — and stemmed from research into the production of nanoparticles in a special organic solvent.

Under certain conditions, the researchers found that the solvent became solid, polymerising.

Prof. Niederberger said: “That was unintentional and unwanted! We didn’t know what to do with it at first either.”

It was then that the team discovered that, alongside a high thermal stability, their new polymer had another intriguing property.

It fluoresces — absorbing and re-emitting light at different wavelengths even though conventional knowledge would suggest it should not be capable of this at all.

Moreover, damaged areas of the coating fail to fluoresce, allowing the team to determine where the protection is worn.

DON’T MISS:

UK could face more delays to rejoining the EU’s £84bn scheme [INSIGHT]

Companies are ‘sleepwalking into climate catastrophe’ [ANALYSIS]

Octopus Energy undercharges thousands by 99.9 percent [REPORT]

With their initial study complete, the researchers are now looking for an industry partner to help them further refine their material for commercial applications.

Paper co-author and doctoral student Marco D’Elia said: “Our technology is pretty advanced, but before we can sell it as a product, there are still some improvements for us to make.”

The team has a patent application on PPM pending.

The full findings of the study were published in the journal Polymers.

Source: Read Full Article