‘Sharkcano’ is erupting! NASA satellite images capture a plume of discoloured water emitting from the Kavachi Volcano where mutant sharks live in an acidic underwater crater

- Satellite images show a plume of discoloured water being emitted from Kavachi

- The data suggests volvanic activity on several days in April and May 2022

- Kavachi has been dubbed ‘sharkcano’ because two species of shark live there

- Scientists believe they have mutated to survive the hot and acidic environment

NASA has warned that a submarine volcano in the Solomon Islands – dubbed the ‘sharkcano’ because two species of shark are known to live in the submerged crater – is starting to erupt.

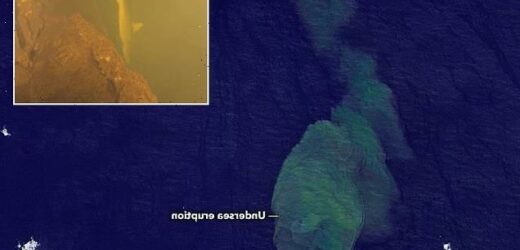

Satellite images show a plume of discoloured water being emitted from the Kavachi Volcano, which lies about 15 miles south of Vangunu Island, on May 14.

The volcano entered an eruptive phase in October 2021, according to the Smithsonian Global Volcanism Program, and the new satellite data suggests activity on several days in April and May 2022.

Previous research has shown these plumes of superheated, acidic water usually contain particulate matter, volcanic rock fragments, and sulphur, according to NASA.

However, this should not be a problem for the resident sharks, which have adapted to thrive in the hot, acidic conditions.

NASA satellite images show a plume of discoloured water being emitted from the Kavachi Volcano, which lies about 15 miles south of Vangunu Island, on May 14

The NASA Earth Observatory images were captured by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the US Geological Survey

Power of underwater volcanoes REVEALED

Explosive volcanic eruptions like the one that devastated Tonga in January are not restricted to shallow water and can occur at depths of ‘at least’ one kilometre (1.6 miles), a study says.

Researchers from the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) have discovered that underwater eruptions are much more powerful than first thought, able to shoot volcanic rock into the air at ‘supersonic’ speeds within seconds.

QUT researcher Scott Bryan said the presence of pink pumice in the water after a 2012 South Pacific eruption situated 900m below sea level was critical to the study.

‘Previous studies thought the magma gently came out of the sea floor and that deep underwater eruptions weren’t able to be explosive,’ Prof Bryan told AAP.

‘But our study shows that Havre was so powerful it was able to punch through almost a kilometre of ocean water to get hot pumice into the air to oxidise and get that colour.’

A 2015 scientific expedition to the Kavachi Volcano found two species of shark – including the scalloped hammerhead and the silky shark – living in the submerged crater.

The researchers also found a sixgill stingray, snapper fish, jellyfish and microbial communities that thrive on sulphur.

The presence of the sharks raised ‘new questions about the ecology of active submarine volcanoes and the extreme environments in which large marine animals can exist,’ the researchers wrote in a 2016 article, ‘Exploring the Sharkcano’.

They believe the sharks must have mutated to survive in the hot and acidic environment.

‘These large animals are living in what you have to assume is much hotter and much more acidic water,’ ocean engineer Brennan Phillips told National Geographic at the time.

‘It makes you question what type of extreme environment these animals are adapted to. What sort of changes have they undergone? Are there only certain animals that can withstand it?’

Kavachi is one of the most active submarine volcanoes in the Pacific and also has the name Rejo te Kvachi, which means Kavachi’s Oven.

The first reports of its activity were recorded in 1939.

There have been at least 11 significant eruptions since the late 1970s, and two – in 1976 and 1991 – were so powerful they created new islands.

However, these islands were not large enough to resist being eroded and ultimately became submerged.

The summit of the volcano is currently estimated to lie 65 feet (20 metres) below sea level; its base lies on the seafloor at a depth of 0.75 miles (1.2 kilometres ).

The frequent shallow submarine eruptions sometimes breach the surface, ejecting jets of steam, ash, volcanic rock fragments, and incandescent ‘bombs’ above the surface.

The news comes after a huge eruption from the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai underwater volcano in Tonga unleashed explosive forces equivalent to up to 30 million tonnes of TNT – hundreds of times more than Hiroshima’s atomic bomb.

The volcano spewed debris as high as 25 miles into the atmosphere when it erupted on January 15.

It triggered a 7.4 magnitude earthquake, sending tsunami waves crashing into the island, leaving it covered in ash and cut off from outside help.

Radar surveys before and after this month’s eruption show only small parts remain of two Tongan islands above the volcano – Hunga Tonga and Hunga Ha’apai.

Tonga underwater volcanic eruption in January was as powerful as Krakatoa in 1883

Tonga’s volcanic eruption in January produced the strongest recorded waves from a volcano since the eruption of Krakatoa in 1883, scientists say.

Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai, an underwater volcano in the South Pacific, created sound waves heard as far as Alaska 6,200 miles away when it erupted on January 15.

Researchers say the eruption was ‘on a par’ with Krakatoa, and the biggest explosion ever recorded by modern geophysical equipment.

It was significantly larger than every atmospheric nuclear bomb test, meteor explosion and volcanic eruption in history, including Mt. St. Helens in 1980 and Pinatubo in 1991.

Barometer readings show the volcano produced a pressure wave that travelled around the world four times over six days – approximately the same as for Krakatoa.

Source: Read Full Article