Living up to their name! Swifts can fly more than 500 MILES in a day – significantly further than previously thought, study finds

- Maximum recorded distance travelled by a common swift is more than 515 miles

- The bird can also travel 354 miles on an average day, experts in Sweden reveal

- Researchers had previously thought the species travels about 310 miles per day

The common swift (Apus apus) can fly more than 500 miles in one day – significantly more than previously thought, a new study based on tracking data reveals.

Scientists had thought the species travels about 310 miles (500 kilometres) per day on average,but this has been revealed as a ‘conservative estimate’.

The medium-sized bird can actually travel 354 miles (570 kilometres) on an average day, but it’s also capable of going much farther and faster.

The maximum recorded distance in the study was more than 515 miles (830 kilometres) per day over nine days.

Incredibly, the common swift spends up to 10 months of the year in the air, assisted by the wind, and can even sleep as it flies.

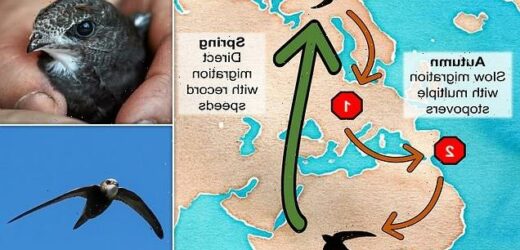

The bird can be found breeding across the UK in spring and summer and migrates southwards to spend the winter months in Africa.

Unfortunately, in just 20 years, more than half of swifts in the UK have vanished, which the RSPB partly blames on the loss of nest sites in the roofs of buildings.

Scroll down for video

Common swifts stay airborne during non-breeding. They live their life in the air where they are continuously exposed to changing weather and winds. Scientists had thought they travel about 500 kilometers per day on average. Now, new evidence reported in the journal iScience on May 20 shows that’s a conservative estimate

THE COMMON SWIFT

The common swift (Apus apus) is a medium-sized aerial bird.

The species is a superb flier and even sleeps on the wing.

It is plain sooty brown, but in flight against the sky it appears black.

It has long, scythe-like wings and a short, forked tail.

It is a summer visitor, breeding across the UK, but most numerously in the south and east. It winters in Africa.

For this new study, researchers based in Sweden used global location sensor tracking to monitor flocks of swifts as they travelled around the world.

Their data revealed estimated overall migration speeds substantially higher than predicted.

‘We have discovered that common swifts breeding in the most northern part of the European breeding range perform the fastest migrations of swifts recorded so far, reaching above the predictions,’ said Susanne Åkesson at Lund University in Sweden.

‘The swifts seem to achieve these high speeds over substantial distances – on average about 8,000 kilometers one way – in spring.’

Researchers used miniature tracking technology based on ‘geolocation by light’ to track adult breeding swifts from a breeding location in Scandinavia.

Geolocation by light allows for tracking animal movements based on measurements of light intensity over time by a data-logging device called a ‘geolocator’.

Although the swift’s air speed is ‘not exceptional’ compared with other migratory birds, such as the great snipe, the new estimates are still impressive for a bird of its moderate size.

The swift achieves its speed using what the researchers call a ‘mixed migration strategy’ – a combination of feeding on the ground during breaks and feeding as they go in the air, something known as ‘fly-and-forage’.

Fly-and-forage works for species that can easily find food along the way instead of loading up before a long trip.

Swifts rely primarily fly-and-forage though – plucking flying insects from the air as they go.

‘The strategy will substantially reduce the cost of transport since they do not need to carry so much fuel, which will increase the realised speed of migration,’ Åkesson said.

Amazingly, the swifts also seem to time their departures for migration such that the winds will be favourable for the coming flight period ahead.

‘This means they do not react directly to local winds but to what they expect to find along the route ahead during the next few days,’ Åkesson said.

The common swift is plain sooty brown, but in flight against the sky it appears black. In just 20 years, more than half of UK swifts have vanished, which the RSPB partly blames on the loss of nest sites in the roofs of buildings

Although it’s not known how they do it, this selective departure strategy means the swifts can gain an extra 20 per cent support from tailwinds in spring as compared to the autumn.

They get the most benefit in terms of speed for crossing the Sahara and the Mediterranean Sea.

‘The airspeed of common swifts is not exceptional (about 10 meters a second) as compared to other bird migrants,’ Åkesson said.

‘But these strategic adaptations contribute to the high overall migration speeds.

‘In addition, their selective use of tailwinds promotes even higher migration speeds, which may explain how they reach above the predicted maximum speed during spring migration.’

Swifts are summer visitors to the UK, but their numbers have suffered a worrying decline over the last few decades

Swifts return to the UK in the spring, around the last week of April or early May, to mate and raise chicks.

But swift numbers in the UK have declined by 57 per cent between 1995 and 2016, according to the RSPB.

The Swedish team also note that a swift’s lifestyle and reliance on insects may put them at risk of dying from pesticide use by humans.

Climate change and changing weather or wind patterns might also have unknown impacts on these extreme fliers.

The study has been published in the journal iScience.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=xvywR4OtSJs%3Frel%3D0%26showinfo%3D1

HOW TO IDENTIFY A SWIFT

Swifts, swallows and martins often get confused for one another, but it’s easier than you might think to tell them apart, according to the RSPB.

Swifts are dark, sooty brown all over, but often look black against the sky.

The wings are long and narrow, with a tail that is slightly forked, but not as much as a swallow’s. Swifts have a piercing, screaming call, but they aren’t noisy at the nest.

Swifts nest in holes – often inside old buildings or sometimes in specially-designed swift nestboxes – so you won’t see them building a nest outside.

You’ll see swifts flying low and fast around buildings, screaming loudly or swooping fast into a little crevice in a building to their nests.

Swift numbers in the UK have declined by 57 per cent between 1995 and 2016, according to the RSPB.

Renovations to roofs and modern building designs mean that there are fewer nest sites for swifts now.

Swifts eat airborne insects and these are also much scarcer too, in large part due to changes in farming practices.

The RSPB is encouraging the public to use their online Swift Mapper tool to log any swift sightings.

This will help locate breeding hotspots for swifts and protect their homes.

Source: Read Full Article