A spongelike structure discovered in exposed 890-million-year-old rock in Canada’s Northwest Territories may be the oldest known fossilized animal body, according to a study whose findings will likely add another controversy to longstanding debates about the planet’s earliest animal life.

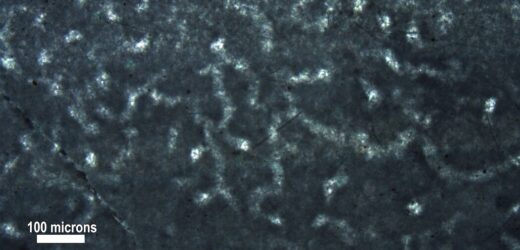

In a paper published Wednesday in the journal Nature, Elizabeth Turner, a geologist at Laurentian University in Ontario, described the branching, tubular structures she observed while examining ultrathin slices — about as thick as a human hair — of what were once reefs in a prehistoric ocean. Dr. Turner suggests the meshlike structures closely resemble the fiber networks of modern keratose sponges, also known as horny sponges, found around the world today.

But she concedes that what she saw under a microscope may not clarify when animal life first emerged on Earth.

“Maybe there is some other explanation. My interpretation is not the final word,” Dr. Turner said. “It’s possible that I’m wrong.”

Some believe she is. “It could just be some microbial wiggles,” said Jonathan Antcliffe, an evolutionary biologist specializing in sponges at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland. The evidence backing up the claim that they’re remnants of an ancient sponge, he said, “is very, very thin.”

The putative fossils were extracted from the 890-million-year-old Little Dal reefs of northwestern Canada, which are now exposed parts of the Mackenzie Mountains. If verified, they would predate the oldest undisputed sponge fossil by about 350 million years — a span of time longer than today and when dinosaurs first evolved.

“We’re talking about inserting hundreds of millions of years without a trace” of fossils, said Graham Budd, a paleobiologist at Uppsala University in Sweden who was not involved in the paper. “It would be sensational. It would be like finding a computer chip in a 14th-century monastery.”

The research highlights the challenges of identifying and making sense of the earliest available fossil records when scientists cannot be sure exactly what to look for, and when there’s not much to look at. “If we expect the first animals to be tiny and soft,” said Maja Adamska, an evolutionary biologist at the Australian National University who was not involved in the new paper, “this is the best we can expect.”

There have been other controversial claims regarding the timeline of the emergence of life on Earth. Discoveries of ancient, “spongelike” fossils have been reported — and later disputed — in Namibia, Russia, Australia, China, Newfoundland and Ukraine. In the early 1990s, scientists at the University of California, Los Angeles, claimed that they had found the world’s oldest, bacteria-forged fossils, which were later dismissed as odd-shaped minerals. In 2016, scientists suggested 3.7-billion-year-old conical structures found in Greenland extended the fossil record back by 200 million years; two years later, three-dimensional analysis refuted the fossil claims.

“The further you go back in time, the more difficult it gets to interpret,” said Gert Wörheide, a paleontologist and geobiologist at Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich. “This is speculation, and that’s fine.”

In the study of sponge evolution, horny sponges are notoriously challenging. They lack many of the animal’s most distinct and fossil-friendly features, including mineralized skeletons and skeleton-like spicule structures. Accordingly, there is no scientific consensus for how to tell their earliest potential fossils apart from the geological traces of ancient organisms such as fungi or bacteria — or something else that has since gone extinct.

“It’s not by chance that this claim is for a group that is incredibly poorly understood,” Dr. Antcliffe said. “It’s an inkblot test. They found something and said, ‘It sort of reminds me of a sponge.’”

In the paper, Dr. Turner argues the squiggly reef microstructures are too consistent and complex to be geological, and do not closely resemble the branching styles of other organisms like fungi or algae.

She adds that a life-form’s evolution does not necessarily begin with its fossil record (which, for sponges, extends back 535 million years).

“They didn’t spring into existence. There has to be a back history to their evolution, potentially a long evolution,” Dr. Turner said. “We haven’t looked hard enough — that’s part of the reason for the gap.”

On Tuesday, Dr. Turner said she was braced for the paper to be met with criticism, given that the field is one so full of uncertainty. “I know it will be a feeding frenzy,” she said. “And that’s OK. Bring it on.”

If her hypothesis bears out, the 890-million-year old sponge fossils prompt other difficult questions: How did sponges survive ice ages and dramatic rises in oxygen? How did they manage to escape fossilization or evade the human gaze until now? And when did animal life truly begin to evolve on Earth?

“We really are far, far beyond the edge of what we can be sure of. This paper shows you how little we know,” Dr. Adamska said. To get any conclusive answers, she said, “We need a time machine.”

Source: Read Full Article