In the early days of the pandemic, Dawn E. Riegner, a chemist at an elite college, found that she had time on her hands because of the empty classrooms. So she filled her downtime with an explosive diversion.

Dr. Riegner talked three of her colleagues — and her daughter — into studying how well different kinds of gunpowder recipes from the Middle Ages performed in firing projectiles out of a replica cannon. Her ambitious plan was relatively easy to carry out because she’s a tenured professor of chemistry at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., which gave her access not only to top scholars and laboratories but world-class firing ranges.

“It’s a silver lining of the pandemic,” Dr. Riegner, whose usual research centers on better detection of explosives and chemical warfare agents, said in an interview of the gunpowder study. “It’s been one of the greatest things.”

During the pandemic’s first wave, early in 2020, the team of West Pointers carefully observed the rules of social distancing, communicating by phone and video chats. The exception was Dr. Riegner and her daughter, Kathleen, who is a student of chemical engineering at the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, N.J. As part of a family pod, mother and daughter were able to work side-by-side in a West Point laboratory. The two chemists measured the oomph of nearly two dozen gunpowder recipes used by medieval gunners between 1338 and 1460.

On a sunny day in June last year, the team of three chemists and two historians (accompanied by a number of safety officers) suited up in masks, helmets and flak jackets at one of West Point’s firing ranges.

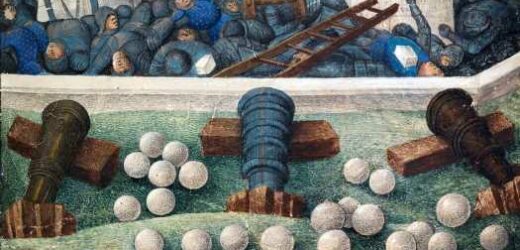

“We were ready for war,” Dr. Riegner joked. “It was great.” In testing each of the various formulations, the replica cannon was fired five times. The deafening blasts produced clouds of dense smoke and fire as well as zooming four-inch cannonballs.

The team’s report on their gunpowder analysis and firings appeared recently in Omega, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Chemical Society.

For ages, the main ingredients of gunpowder have consisted of sulfur, carbon and potassium nitrate, commonly known as saltpeter. The sulfur and carbon (typically in the form of charcoal) act as fuels whereas the saltpeter provides a rush of oxygen to ignite the extremely fast chemical reaction known as explosive combustion.

The medieval recipes of the team’s study featured different ratios of those main ingredients. But they also included a number of unusual additives. For instance, one recipe called for brandy. The team noted that they used Paul Masson, Grande Amber, a contemporary brand. (The paper does not say if the experimenters used the leftovers to toast the cannon firings).

Other ingredients were less potable: camphor and quicklime, varnish and vinegar. The goal was to measure the explosive power of each mix.

The study could also cast light on history. The authors see the gunpowder analyses as aiding historians in their interpretation of medieval texts and in determining the extent to which master gunners in crafting the recipes did so with deliberate intent.

Dr. Riegner credited her colleague, Clifford Rogers, a historian at West Point and a co-author of the study who specializes in medieval arms and warfare, with the idea of using modern chemistry to investigate the detailed characteristics of the old recipes.

In an interview, he said cannons — or more precisely, bombards, an early cannon that fired stone balls and first appeared in Europe in the early 1300s — kept getting safer, bigger, more powerful and far more effective over time. A main question for the investigative team, he said, was to pin down the exact role of the changing gunpowder recipes in cannon improvement.

The earliest big guns blew up “a lot,” Dr. Rogers said. The blasts killed gunners and, in one case, a Scottish king. He pointed to a siege in 1409 of a fortress in Vellexon, France, as an example of the failures. The siege, conducted by Burgundians against a rebel lord during a period of civil war, employed eight bombards to pummel the walls of the castle with large cannonballs — and two of the artillery pieces exploded. The siege dragged on without success for months.

In its gunpowder analyses, the team found that the amount of heat released during an explosion fell steadily from the 1330s to 1400 — suggesting, the report stated, “the need for safer recipes that did not put medieval gunners at risk or cause damage to cannons.” At the same time, the newest guns got bigger and far more effective.

Dr. Rogers called it a turning point in Western history.

“It mattered hugely because it changed the balance between offense and defense,” he said. Castles and fortresses had long been invulnerable. By the 1400s, however, the big guns had improved so dramatically that successful sieges began to shorten in length from years and months to weeks and days.

“You could no longer hole up in your castle,” Dr. Rogers said. “If you wanted to defend your country, you needed an army rather than just a fortress.” The geopolitical result was vast, he added. “It completely changed the nature of warfare.”

Dr. Riegner, the study’s lead chemist, said the five experts were planning new rounds of investigations to better document the subtle effects of the different recipes. But the ebbing of the pandemic and the reopening of schools had created a problem, she added. Team members — including herself and her daughter — no longer have plenty of time on their hands.

“We’re all interested and excited but now, with the return to the classroom, we have other duties,” she said. “Maybe in the spring we’ll be able to work it out.”

Source: Read Full Article