Olive jars, gold chains and coins are among a treasure trove of new artefacts from a legendary shipwreck that has been hidden beneath the Bahamas’ shark-infested waters for 350 years

- Nuestra Señora de las Maravillas was a two-deck Spanish galleon laden with treasures for royalty and wealthy

- In 1656, she sank rapidly after colliding with its flagship and hitting a reef, leading to the death of 600 people

- Some of the items were contraband that was ‘illegally greasing the palms of Spanish merchants and officials’

- Experts say the wreck has been ‘pounded into oblivion’ and is heavily scattered because of salvage attempts

Divers have revealed new treasures from a legendary 17th century shipwreck that have been hidden beneath the Bahamas’ shark-infested waters for 350 years.

The Nuestra Señora de las Maravillas (Our Lady of Wonders) was a two-deck Spanish galleon ship that sank off the Little Bahama Bank in the northern Bahamas on January 4, 1656.

The majority of its treasure – an estimated 3.5 million pieces of eight – was salvaged between 1656 and the early 1990s, but recent efforts using modern technology have uncovered artefacts on the ship that have never been touched since the sinking.

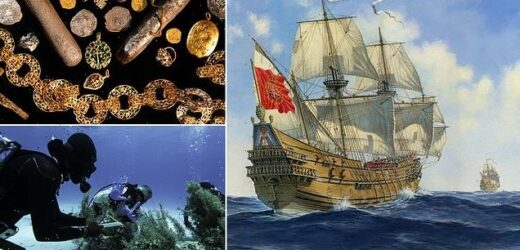

Included in the hoard are Spanish olive jars, Chinese porcelain, iron rigging, and gold and silver coins, as well as a silver sword handle that belonged to the soldier Don Martin de Aranda y Gusmán.

Three gold chains have also been saved, as well as four pendants worn by members of the sacred Order of Santiago, a religious band of knights deeply active in Spanish maritime trade.

Some of the items were contraband that was ‘illegally greasing the palms of Spanish merchants and officials’.

All these finds are unique among the world’s three million shipwrecks, according to experts, and will be exhibited at a new museum at the Bahamas for the first time staring next week.

Included in the hoard are Spanish olive jars, Chinese porcelain, iron rigging, and gold and silver coins, as well as a silver sword handle that belonged to the soldier Don Martin de Aranda y Gusmán. Pictured, high-status personal belongings – gold jewellery, chain, pendants and coins from the Maravillas

Artist’s depiction of the Nuestra Señora de las Maravillas (Our Lady of Wonders), a two-deck Spanish galleon armed with 36 bronze cannons

Nuestra Señora de las Maravillas (Our Lady of Wonders) sank off the Little Bahama Bank in the northern Bahamas on January 4, 1656

HISTORY OF THE ‘NUESTRA SEÑORA DE LAS MARAVILLAS’

The Nuestra Señora de las Maravillas (Our Lady of Wonders) was a two-deck Spanish galleon armed with 36 bronze cannons.

In 1654 it was serving as the Almirante (vice-flagship) of the Tierra Firme (Mainland) fleet when it sank.

It was carrying ‘treasure’ to Seville, both as royal tax and private property.

Maravillas was unusual because it was transporting a double cargo – both its own consignment of silver, as well as silver salvaged from the wreck of the Jesús María de la Limpia Concepción that was supposed to supply the 1654 fleet but sank off Ecuador in October 1654.

Near midnight on January 4, 1656, Maravillas and her flagship, Nuestra Señora de la Concepción, collided.

Its planks broke between the top of the waterline and the holds. In under 30 minutes after the collision, the Maravillas violently struck a reef and sank.

Around 600 of the 650 people on board died.

‘The Maravillas is an iconic part of The Bahamas’s maritime history,’ said Carl Allen, founder of Allen Exploration, which led the recent expeditions.

‘We’re delighted to be licensed by the Bahamian government to explore the Maravillas scientifically and share its wonders with everyone in the first maritime museum in The Bahamas.’

The 891-ton Our Lady of Wonders was part of the Tierra Firme (Mainland) fleet, homeward-bound to Spain from Havana, Cuba, laden with royal and private consignments.

Also onboard Our Lady of Wonders was a former Spanish cargo wrecked off Ecuador a year and a half earlier, weighing the ship down further.

She ended up colliding with her fleet flagship, hitting a reef 30 minutes later and sinking rapidly. The majority of the 650 people on the galleon grabbed hold of floating debris and drifted away, never to be seen again.

About 150 clung to pieces of the galleon still above the water. Most died from exposure during the night or were eaten by sharks. Overall, only 45 people survived and around 600 people were lost.

The wreck was quickly relocated after sinking in January 1656, and by July 1658, Spanish records show that the wreck was completely buried under sand.

Many Spanish, English, French, Dutch, Bahamian and American salvors later tried to recover the wreck and the treasures within but had little success.

In the modern era, it was rediscovered by Robert Marx in 1972 who heavily salvaged remains. Further remains were salvaged by Herbert Humphreys between 1986 and the early 1990s, but according to Allen Exploration what’s left of the ship have been ‘pounded into oblivion’.

‘The wreck of the galleon had a tough history,’ said Allen. ‘[It was] heavily salvaged by Spanish, English, French, Dutch, Bahamian and American expeditions in the 17th and 18th centuries, and blitzed by salvors from the 1970s to early 1990s.

‘Some say the remains were ground to dust. Using modern technology and hard science, we’re now tracking a long and winding debris trail of finds.’

In 2019, after the Bahamian government granted it a license to explore the wreck, Allen Exploration used a vast network of 8,800 magnetometers – devices that measure anomalies in the Earth’s magnetic field, caused by the presence items with magnetic properties.

These mapped the location of the untouched artefacts, from potsherds and iron hull fasteners to rigging, coins, ballast and high-status goods.

Divers were also employed to recover them and bring them back to land for the first time in 350 years. Now the collection is back on land, Allen Exploration has no intention to split it up or sell it.

The ship’s debris trail spans a whopping eight miles (13km), although Allen Exploration is not releasing information about its exact position to protect the site.

One of the ‘stunning’ discoveries is an 887-gram gold filigree chain, about 70 inches long, made up of 80 alternating circular flat and tubular links, decorated with four-lobed rosette motifs.

It was intended for a wealthy aristocrat or even royalty, and was probably crafted in the Philippines from local gold using Chinese craftsmen, and then exported to Spain by way of Mexico on a Manila galleon.

Another item is an oval-shaped golden pendant with a gold Cross of St. James on top of a large green oval Colombian emerald.

The outer edge is framed by 12 more square emeralds, perhaps symbolising the 12 apostles.

A unique golden filigree chain from the Nuestra Señora de las Maravillas (Our Lady of Wonders), probably made in Manilla, the Philippines

A second golden pendant found on the Maravillas’ debris trail is oval in shape and 4.7 centimeters long. At its center a gold Cross of St. James overlies a large green oval Colombian emerald. The outer edge is framed by 12 more square emeralds, perhaps symbolizing the 12 apostles

A gold and pearl ring from the Maravillas shipwreck. New finds are unique among the world’s three million shipwrecks, according to experts, and will be exhibited at a new museum at the Bahamas for the first time

Allen said the priceless artefacts were found lying on ‘dead gray reefs’ and that seeing the sea floor gave him ‘mixed feelings’.

‘The sea bottom is barren,’ he said. ‘The colorful coral that divers remembered from the 1970s is gone, poisoned by ocean acidification and choked by meters of shifting sand. It’s painfully sad.

‘Still lying on those dead gray reefs, though, are sparkling finds: olive jars, the spikes that held the Maravillas together, the odd cannon and anchors.’

Silver and gold coins and emeralds and amethysts, as well as a 75-pound silver bar, are among those thought to be illegal contraband consignments, unauthorised by the Spanish Crown.

Spanish Americas’ galleons carried at least 20 per cent contraband above what was declared on manifests, some even over 200 per cent.

Allen Exploration’s Bahamas Maritime Museum – in the city of Freeport, Grand Bahama – will open on August 8.

An ‘olive’ jar from the wreck of the Maravillas, used to transport general foodstuffs. Allen Exploration has no intentions to split up the collection or sell it

Personal belongings range from the silver sword hilt of the soldier Don Martin de Aranda y Gusmán to a pearl ring, two glass wine bottles and four pendants worn by knights of the Order of Santiago. Pictured, a glass wine bottle discovered on the Maravills wreck site

Gold and bezoar stone scallop-shaped pendant of the Order of Santiago with a cross of St. James at its centre from the Maravillas shipwreck

Allen Exploration’s Bahamas Maritime Museum (pictured) in the city of Freeport, Grand Bahama will open next Monday, August 8

UK’S MOST AMAZING SHIPWRECKS REVEALED: FROM HMS INVINCIBLE IN PORTSMOUTH TO WHITBY’S CONCRETE CRETEBLOCK

A whopping 350 years after it sank off the coast of Norfolk, authorities revealed in June that HMS Gloucester has finally been found.

The ‘outstanding’ ship, which sank on May 6, 1682 after hitting the Norfolk sandbanks in the southern North Sea, was uncovered 28 miles off the coast of Great Yarmouth half-buried on the seabed.

But HMS Gloucester is just one of thousands of shipwrecks that litter the British coast, the majority of which haven’t been seen by the human eye for centuries.

It’s thought nearly 40,000 wrecks could be waiting to be found off the British coast, according to Historic England, providing snapshots of the UK’s rich maritime heritage.

But at least 90 are known to exist and experts have pinpointed their location, although many likely won’t ever be brought to land and could disintegrate to nothing in the decades to come.

MailOnline has taken a look at some of the most amazing shipwrecks around Britain, from HMS Invincible in Portsmouth to Tabarka in the Orkney Islands and a rare concrete ship in Whitby.

Some can be seen sticking out of sands at low tides, while others are deep underwater, partly submerged in the seabed, and can only be seen during authorised dives.

Read more

Source: Read Full Article