Tutankhamun: 'Curse' of Pharaoh's tomb discussed by historian

We use your sign-up to provide content in ways you’ve consented to and to improve our understanding of you. This may include adverts from us and 3rd parties based on our understanding. You can unsubscribe at any time. More info

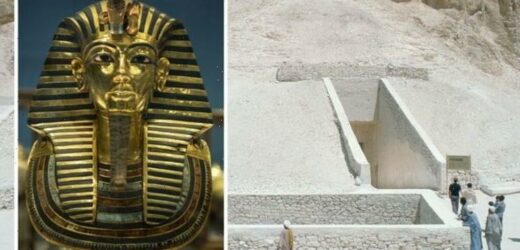

King Tut’s death has been the subject of considerable debate and major studies among academic circles. The ancient Egyptian pharaoh took the throne when he was just eight or nine-years-old, and ruled Egypt for around a decade until his death in roughly 1324 BC. Though his rule was important for reversing many of the controversial reforms his father, Akhenaten, had implemented, King Tut remained a minor figure in ancient Egyptian history until only recently. British archaeologist Howard Carter discovered King Tut’s tomb in 1922, when he chiseled through a doorway and entered the pharaoh’s tomb, which had remained untouched for some 3,200 years.

The tomb contained more than 5,000 artefacts, including a solid golf coffin, a gilded mask and thrones.

It took Mr Carter 10 years to record all of the items.

The one thing he did not find, however, is any record of how Tut died.

There are no surviving records of the circumstances of King Tut’s death.

Murder had been speculated as a possible cause after an x-ray in 1968 showed two bone fragments inside the skull.

/news/science/1526992/Egypt-Tutankhamun-mysteries-solved-evg

Theories then emerged that the young king had been brutally murdered by political enemies, during an especially volatile period of Egyptian history.

While Mr Carter and his colleagues were removing the body, it was damaged.

King Tut had been affixed to his coffin by resins used in the embalming process.

In the process of removing the body from the coffin, much of the mummy was dismembered — and it was difficult to distinguish some of the damage from the embalming process from damage dating back to Tut’s lifetime.

However, further analysis of the 1968 x-rays, as well as a CT scan, put murder theories to bed.

The bone fragments in King Tut’s cranial cavity exactly matched two missing pieces of bone from his first vertebra, located in the neck.

They were loose fragments and were not covered in the embalming resin, which allowed scientists to conclude that it had been the result of the modern unwrapping of the mummy.

Radiologist Ashraf Selim told National Geographic: “If these pieces of bone [were dislodged] before death, we would assume they would be stuck to the resin inside the skull, not just loose there.”

Mr Selin believed they may have been dislodged during first attempts to remove King Tut’s now iconic gold mask, which was tightly glued to his body.

Addressing the murder theory, he said: “I think it is the end of the investigation… We can now close this file.”

DON’T MISS:

Antarctica discovery offered stunning evidence for life [INSIGHT]

Archaeology: ‘Unexpected’ Solent discovery rewrites farming history [REVEALED]

Stonehenge discovery stunned researchers: ‘Rewrites understanding’ [QUOTES]

His team shifted their focus to King Tut’s left leg, suggesting that a fracture in the thigh bone might have played a significant role in his death.

A thin coating of the embalming resin could be seen on the CT scan around the area of the fracture.

It has been speculated that a combination of King Tut’s multiple weakening disorders, a leg fracture and a severe infection could have caused his death.

Mr Selin said: “The resin flowed through the wound and got into direct contact with the fracture and became solidified, something we didn’t see in any other area.

“We could not find any signs of healing of the bone.”

Given that there were no antibiotics 3,000 years ago, it is highly likely that a severe infection could have resulted from the break.

Mr Selin said: “It’s probably what killed him.”

Fellow radiologist John Benson told National Geographic in 2006 that the leg break is likely to have caused King Tut’s death, but there will “always” be speculation.

He said: “There are a number of possible causes of death for which there would be no residual evidence.

“Tut could have had pneumonia, or he could have died from a communicable disease.

“Maybe his immune system was a little impaired because he was trying to heal the fracture, and he caught some kind of other disease that we wouldn’t really be able to prove one way or the other.”

Meanwhile, a German team of archaeologists have argued King Tut was killed by the inherited blood disorder sickle-cell disease (SCD).

Christian Timmann and Christian Meyer pointed out that SCD is the most common cause of bone damage like King Tut’s.

People with SCD can still carry the malaria parasite in their blood, despite having increased immunity brought about by the presence of the sickle-cell gene.

This, they argued, would explain why they detected the genes of the malaria parasite.

Their theory was labelled “interesting and plausible” by Egypt’s chief archaeologist Zahi Hawass and his colleagues, who had suggested that malarial infection was the fatal blow after weakening disorders and a leg fracture.

Source: Read Full Article