SpaceX launches batch of Starlink satellites with Falcon 9

We use your sign-up to provide content in ways you’ve consented to and to improve our understanding of you. This may include adverts from us and 3rd parties based on our understanding. You can unsubscribe at any time. More info

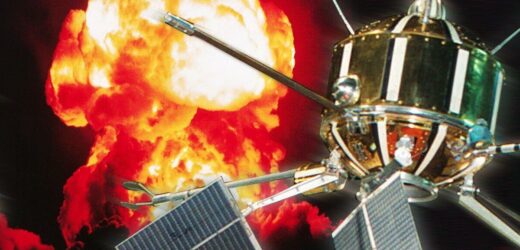

Today marks the 60th anniversary of the Ariel 1 satellite. It was the first British satellite and the first satellite in the Ariel programme. Launched in 1962, it made the UK only the third country to operate a satellite, after the Soviet Union and the US.

Ariel 1 was constructed in both the UK and the US by NASA Goddard Space Flight Centre and SERC, under an agreement reached between the two countries in 1959 and 1960.

Its mission was to investigate the Earth’s upper atmosphere and study the effects of X-ray radiation from the Sun.

The scientific satellite had performed faultlessly until transmissions ceased suddenly on 13 July.

The date of its demise was no coincidence either: it failed four days after the US detonated a 1.4 megaton nuclear warhead in an experiment known as Starfish Prime.

It took place high in the atmosphere, around 400 kilometres (250 miles) above the Pacific Ocean.

The explosion — the world’s most powerful high altitude nuclear test — created an electromagnetic pulse (EMP) strong enough to disrupt global radio communications and even blow out streetlights on the ground in Hawaii.

It also created a new, temporary radiation belt around the Earth.

This belt was the ultimate match for Ariel 1 that led to its destruction.

UK Government documents detailing the satellite’s fate remained locked away for 50 years.

JUST IN: Russia’s ‘only oil pipeline to EU’ in flames – 3 countries face crisis

An article for BBC Future said it is “clear why” the documents were kept marked as top secret for so long.

While NASA realised almost immediately what had happened to the satellite, the UK was, embarrassingly, kept in the dark.

When British officials pieced together the story, Lord Hailsham, the science minister, was the one to tell Prime Minister Harold Macmillan.

His 1962 memo, typed over two pages, relates the saga: “Although badly wounded in his solar paddles he is not quite dead.

“He still utters intermittently – sometimes intelligibly.

“He may still improve sufficiently to tell us something of value, though he can hardly say ‘merrily shall I live now’.”

DON’T MISS

Energy grid will be stable ‘every minute of every day’ with green push [REPORT]

Putin facing brink: Exiled oligarch says EU sanctions would be ‘blow’ [INSIGHT]

Forget Satan 2! US £157bn project can wipe out Putin’s missile [ANALYSIS]

Lord Hailsham’s memo suggests that the UK’s financial loss from the projects was relatively small compared to the US, who put up the bulk of the cash.

He added that the satellite had already proved its scientific worth.

He continued: “We have got a great deal out of him during his life (short, but neither nasty nor brutish).

“Before his accident, he had transmitted for approximately a thousand hours, and it will take at least a year to analyse the significance of what he has said.”

Ariel 1 was not the only satellite badly affected by the Starfish Prime nuclear explosion.

The test has also been blamed for the premature failure of the world’s first TV communications satellite, Telstar.

While Lord Hailsham warned that “the real moral about their high-level explosion is the need for a test ban treaty”, military strategists noted the effects of the weapon with interest.

They wondered whether nuclear or EMP weapons could be used to knock out spacecraft.

This might, they said, entail disrupting an enemy’s communications, defences or spy satellites or even a nation’s ground-based electrical infrastructure

Elizabeth Quintana, director of military sciences for the Royal United Services Institute, told the BBC: “EMP weapons are not a capability that’s widely talked about.

“But they are in current military inventories.”

EMP weapons systems are designed to be deployed by ground forces or aircraft, and are capable of either frying all electronic systems in a particular area or targeting specific wavebands, like disrupting a nation’s radar defence systems.

But, aside from fears of collateral damage, one of the big concerns with deploying EMP devices is that the effect is hidden.

Ms Quintana said: “When you deliver a bomb it’s quite obvious what damage you’ve done.

“It’s much harder to do that with EMP.

“While it’s a stealthy way of delivering a temporary effect – such as knocking out enemy air defences as you’re travelling through it may not be effective.”

While fears that this EMP technology has since been a hot topic of discussion for governments and military strategists, many, like Ms Quintana, remain unconvinced.

Source: Read Full Article