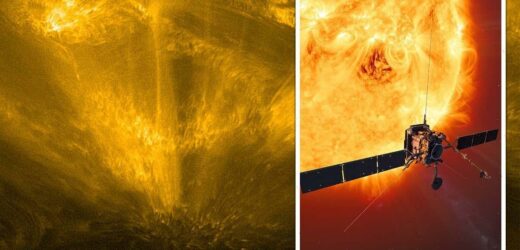

European Space Agency share footage of ‘solar hedgehog’

We use your sign-up to provide content in ways you’ve consented to and to improve our understanding of you. This may include adverts from us and 3rd parties based on our understanding. You can unsubscribe at any time. More info

Launched back in early 2010, the Solar Orbiter was built to take detailed measurements of the region around the Sun and also make observations of the star’s poles, which is difficult to do from here on Earth. The craft made its closest approach to the Sun — the so-called “perihelion” — on March 26 this year, travelling within the orbit of Mercury, around a third of the Earth-Sun distance away from our host star. According to ESA scientists, the craft’s heat shielding reached a scorching 932F (500C), although it was capable of dissipating this using special technology.

Solar physicist Dr David Berghmans of the Royal Observatory of Belgium said: “The images are really breathtaking.”

Dr Berghmans is the principal investigator behind Solar Orbiter’s Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI), which takes high-resolution images of the corona, the layer of the Sun which drives most space weather activity.

The EUI team find themselves faced with a daunting analysis — with the spacecraft revealing so much small-scale activity on the Sun that merits interpretation.

Dr Berghmans added: “Even if Solar Obiter stopped taking data tomorrow, I would be busy for years trying to figure all this stuff out.”

During the recent perihelion, one feature of a particular note has caught the researchers’ attention — a solar structure that the experts have dubbed “the hedgehog”.

As the name suggests, the feature sports a multitude of spikes of hot and colder gas that reach out in all directions, spanning a whopping 15,534 miles.

While the hedgehog is quite distinctive, Solar Orbiter is also looking at more subtle phenomena — such as the effect that the Sun has on the heliosphere.

The heliosphere is the name given to the large “bubble” of space, which encompasses the orbits of all the planets in the solar system, that is filled with electrically charged particles.

It is the movement of these particles, most of which have been expelled by the Sun, and their associated magnetic fields that create space weather phenomena that can lead to auroras, communications interference and power fluctuations here on the Earth.

Sun: Footage shows Solar Orbiter’s closest approach to star

Solar Orbiter’s in-situ instruments measure the particles and magnetic fields of the heliosphere along its passage through space — and then scientists try to link these traces back to events on or near the surface of the Sun as detected by remote sensing instruments.

According to the ESA, “This is not an easy task as the magnetic environment around the Sun is highly complex.

“But the closer the spacecraft can get to the Sun, the less complicated it is to trace particle events back to the Sun along the ‘highways’ of magnetic field lines.

“The first perihelion was a key test of this, and the results so far look very promising.”

DON’T MISS:

The NATO weapon that Putin ‘really fears’ [INSIGHT]

Finland sends defiant message to Russia after voting to join NATO [REPORT]

Europe is sitting on enough gas reserves to replace 22 year’s Russoa supply [ANALYSIS]

Data like this will help to develop future systems for monitoring the space weather conditions around the Earth in real-time.

In fact, in the run-up to the perihelion — on March 10, to be exact — a coronal mass ejection (CME) passed over the Solar Orbiter on its way to hit Earth.

CMEs are one of the most powerful forms of solar storm, manifesting as a cloud of charged particles and electromagnetic fluctuations that belches out from the Sun’s surface.

Thanks to data collected by the craft’s magnetometer instrument, the ESA was able to provide 18 hours’ worth of advance notice on Twitter for space enthusiasts to keep an eye out for the auroras generated by the CME.

![]()

The ESA said: “The perihelion was a huge success and has generated a vast quality of extraordinary data. And it’s just a taste of what is to come.”

On September 4 this year, the craft will make its third flyby of Venus, lining itself up for its next — and slightly closer — flyby of the Sun on October 13, at just 0.29 times the Earth–Sun distance.

Two subsequent encounters with Venus — one on February 18, 2025, and the other on December 24, 2026 — will increase the spacecraft’s orbital inclination to 24 degrees.

This will mark the beginning of Solar Orbiter’s “high-latitude mission”, which will give scientists the most direct look to date at the Sun’s polar regions — and perhaps allow scientists to untangle the mystery of the Sun’s 11-year activity cycle.

ESA Solar Orbiter project scientist Daniel Müller said: “We are so thrilled with the quality of the data from our first perihelion.

“It’s almost hard to believe that this is just the start of the mission. We are going to be very busy indeed.”

Source: Read Full Article