A young female mammoth was wandering long ago near what would become the Central Coast of California, when her life came to an untimely end. Although she died on land, her massive body found its way into the Pacific Ocean. Carried by currents, her remains drifted more than 150 miles from shore before settling 10,000 feet beneath the water’s surface on the side of a seamount. There she sat for millenniums, her existence known to no one.

However, that all changed in 2019 when scientists from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute stumbled upon one of her tusks while using remotely operated vehicles to search for new deep-sea species off the coast of Monterey, Calif.

“We were just flying along and I look down and see it and go ‘that’s a tusk,’” said Randy Prickett, a senior R.O.V. pilot at the institute. Not everyone believed him at first, but Mr. Prickett was able to convince his colleagues to go in for a closer look. “I said ‘if we don’t grab this right now you’ll regret it.’”

The crew attempted to collect the mysterious object. To their dismay, the tip of the scimitar-shaped specimen broke off. They picked up the small piece and left the rest behind.

It wasn’t until the scientists examined the fragment that they were sure that what they had stumbled upon was indeed a tusk. But from what animal and what time period was still unknown.

The discovery of such a specimen in the deep sea is unusual. Tusks and other skeletal remains of prehistoric creatures are usually found deep underground or encased in permafrost near the Arctic Circle. Although some specimens have been found in shallow waters in Western Europe’s North Sea, the remains of a mammoth, or any ancient mammal for that matter, have never been found in waters so deep.

Steven H.D. Haddock, a marine biologist at the institute who led the 2019 survey, usually focuses on bioluminescence and the ecology of gelatinous deep-sea organisms. But he couldn’t resist the allure of this scientific stumper. So he put together a team of scientists from the institute, the University of California, Santa Cruz and the University of Michigan to solve the mystery.

Preliminary research by Dr. Haddock’s colleagues presented the possibility that this wasn’t just any mammoth — instead, it might have been one that died during the Lower Paleolithic, an era that lasted 2.7 million through 200,000 years ago and from which well-preserved specimens are sparse.

Further study of this specimen may help answer long-held questions about the evolution of mammoths in North America. The discovery also suggests that the ocean floor could be covered in paleontological treasures that will add to our knowledge of the deep past. But before the team could really advance the science, they’d have to head back out to sea to collect the rest of the tusk.

On July 27, I boarded the Western Flyer, MBARI’s largest research vessel, with an assortment of other crew. Along for the ride were Daniel Fisher, a paleontologist at the University of Michigan who studies mammoths and mastodons, and Katherine Louise Moon, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Santa Cruz who studies the DNA of ancient animals.

Before the outing, Dr. Moon was able to extract just enough DNA from the broken tip to determine that the tusk came from a female mammoth. Her conclusion was supported by Dr. Fisher, who said the tusk’s shape and size were characteristic of a young female mammoth. Terrence Blackburn, another researcher at Santa Cruz, was unable to join the trip, but his preliminary work also provided an estimate of how many years it had been since the mammoth died.

Back on the boat, it took two days to reach the undersea mountain where the tusk was as Dr. Haddock and his colleagues stopped at various points along the way to collect rare and undescribed species of jellyfish and ctenophores, invertebrates also known as comb jellies. The sun was barely cresting the horizon on the morning of July 29 when the boat finally reached its target. Dr. Haddock and his team wasted no time getting their search underway, stationing themselves in the ship’s control room while the rest of the crew was still eating breakfast.

An air of excitement filled the dark room as the scientists watched on screens while the R.O.V., named the Doc Ricketts after the famous marine biologist who influenced John Steinbeck, slowly descended into the depths. By the time the aquatic drone had reached its destination, the side of a seamount some 10,000 feet deep, the room was packed with scientists, engineers and members of the ship’s crew, all eager to witness the rediscovery of the tusk.

Almost everything on the sloping seamount below the R.O.V. was covered in a black iron-manganese crust. That at first made spotting the tusk difficult. However, after less than 15 minutes of searching, the quarry suddenly appeared on one of the screens.

“It’s exactly how we left it,” Dr. Haddock said.

The crew was delighted, but they couldn’t celebrate just yet. They still had to collect the tusk, and there was no guarantee it would go smoothly. Dr. Haddock and his team were concerned that the long tooth might be too fragile to pick up, so they took their time recording photos and videos that could be used to create a 3-D model in case it broke during their recovery attempt.

Household sponges and soft plastic fingers had been attached to the arms of the vehicle to make it easier for the pilots to gently pick up the tusk. The room fell silent as the grippers reached for the encrusted fossil. Everyone in the room watched nervously as the robot lifted the tusk. Then, ever so gently, the drone moved the object into its collection drawer. The second the tusk was released, the silence was broken by a torrent of applause. The tusk had been found and recovered in just under two hours.

A short while later, the R.O.V. returned to the surface and was brought back onboard the ship. Dr. Haddock and Dr. Fisher moved the tusk to the ship’s lab and wasted no time measuring, cleaning and photographing the specimen.

After donning a pair of gloves and some sterile coveralls, Dr. Moon joined in. She pulled out a wire saw and sliced a chunk of the tusk off, allowing her to sample its innermost tissue. She said she hoped this sample contained more mammoth DNA than was recovered from the sampling of the tusk’s tip two years ago — enough to determine the species of mammoth that ended up in this watery grave, as well as its lineage.

“We’re all incredibly excited,” Dr. Moon said. “This is an Indiana Jones mixed with Jurassic Park moment.”

Under the Sea: Recovering Ancient Treasure

Under the Sea: Recovering Ancient Treasure

On July 27, scientists working with the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute boarded a research ship to hunt for an ancient treasure near California’s coast.

I watched them retrieve it and took some pictures →

Under the Sea: Recovering Ancient Treasure

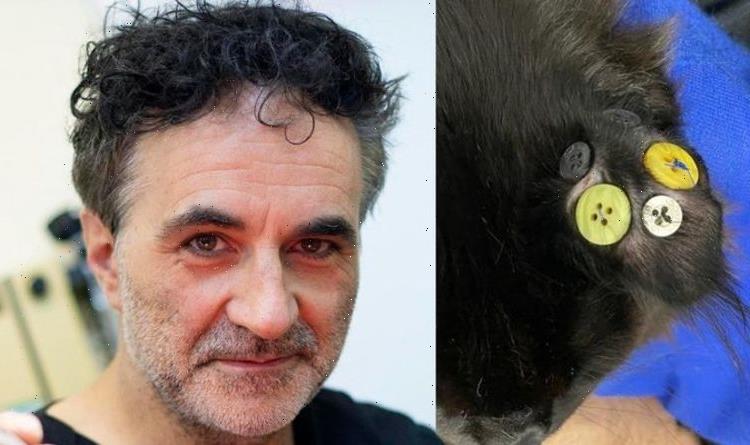

The treasure wasn’t a sunken ship: It was the tusk of a mammoth. This was highly unusual: Prehistoric animal remains are usually found deep underground or in permafrost, not on the seafloor. I decorated this cup to commemorate the trip to find it.

Under the Sea: Recovering Ancient Treasure

Scientists with the Monterey Bay research team, led by Steven Haddock, had spotted the tusk in 2019. However, they were only able to collect a small piece. Analysis of that chunk suggested it preserved information from the Lower Paleolithic, a poorly understood era of Earth’s history.

Under the Sea: Recovering Ancient Treasure

On July 29, the ship reached the site where they had originally found the tusk and sent a remotely operated vehicle to retrieve the rest. I was watching the operation in the control room, and surprisingly spotted it on a screen first. The researchers and pilots shared a brief moment of elation.

Under the Sea: Recovering Ancient Treasure

The pilots managed to collect the tusk without any issues. When the underwater drone returned, many of the ship’s crew gathered to watch the researchers unload its haul. Such a specimen had never been collected from waters so deep.

Under the Sea: Recovering Ancient Treasure

The tusk smelled of a musty garage and was covered in a thick iron-manganese crust. It was cleaned and examined by Daniel Fisher of the University of Michigan and samples were collected by Katherine Louise Moon of the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Under the Sea: Recovering Ancient Treasure

The researchers sent the remote vehicle back down to the deep sea a few more times before the trip was over. During one of those dives, the cup I decorated got to hitch a ride. Here is how it looked after spending a few hours 2,000 feet below the ocean’s surface.

Read more about the discovery of an ancient mammoth tusk deep in the Pacific Ocean.

Source: Read Full Article