Teenage T. rex was a TYRANT! Young giant carnivorous dinosaurs made up a significant portion of the population and outcompeted smaller rivals for food

- As a group, dinosaurs are less diverse than other species in the fossil record

- Experts studied the sizes of some 550 dinosaur species from around the world

- A gap between small and big species appears when megatheropods are present

- The species that would fill this gap were ousted by the young giant dinosaurs

- Megatherapods include species like Abelisaurs, Allosaurus and the iconic T. rex

If you thought the ‘youths’ of today were bad, think again — for teenage T. rex and adolescent Allosaurus outcompeted smaller rival species for food, a study found.

US experts found that the young of giant carnivorous dinosaurs, or megatheropods, acted as their own ecological entity in both the Jurassic and Cretaceous Periods.

They were so dominant that they actually re-shaped their communities, making up a significant proportion of the population and replacing medium-sized species.

This, the team said, explains why carnivorous dinosaurs tended to only come in two adult sizes, small and massive, rather than a more diverse spread of proportions.

Furthermore, it explains why there are more large than small species of dinosaurs — and why, compared to other fossil species, dinosaur species are not very diverse.

Scroll down for video

If you thought the ‘youths’ of today were bad, think again — for teenage T. rex and adolescent Allosaurus outcompeted smaller rival species for food, a study found. Pictured: a model T. rex

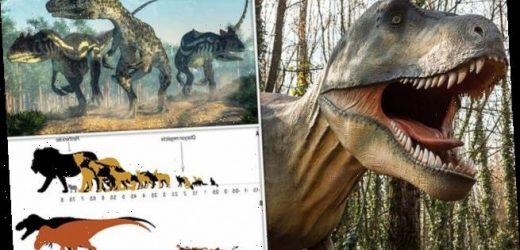

US experts found that the young of giant carnivorous dinosaurs, or ‘megatheropods’, acted as their own ecological entity in both the Jurassic and Cretaceous Periods. Pictured: an artist’s impression of a gang of three Allosaurus on the hunt

T. REX: THE BASICS

Tyrannosaurs rex was a species of bird-like, meat-eating dinosaur.

It lived between 68–66 million years ago in what is now the western side of North America.

They could reach up to 40 feet (12 metres) long and 12 feet (4 metres) tall.

More than 50 fossilised specimens of T. rex have been collected to date.

The monstrous animal had one of the strongest bites in the animal kingdom.

‘Dinosaur communities were like shopping malls on a Saturday afternoon — jam-packed with teenagers,’ said paper author and palaeobiologist Kat Schroeder of the University of New Mexico.

‘They made up a significant portion of the individuals in a species and would have had a very real impact on the resources available in communities.’

Because they hatched from eggs — like their modern counterparts, birds — dinosaurs were necessarily born small.

In fact, young dinosaurs like T. rex tend to start off about the size of a housecat or small dog — before growing to around the size of a bus and ending up weighing in at some 1–8 tonnes.

It had long been thought that this remarkable transformation must have been accompanied by changes in the prey they sought with age and, by extension, the kinds of hunting strategies they used to capture such as they grew larger.

It had not been clear, however, how the growth of megatheropods affected the world around them.

‘We wanted to test the idea that dinosaurs might be taking on the role of multiple species as they grew, limiting the number of actual species that could co-exist in a community,’ explained Ms Schroeder.

‘Dinosaurs had surprisingly low diversity,’ added paper author and biologist Felisa Smith, also of the University of New Mexico.

‘Even accounting for fossilization biases, there just really weren’t that many dinosaur species,’ she added.

Juvenile megatheropods were so dominant that they actually re-shaped their communities, making up a significant proportion of the population and replacing medium-sized species. Pictured, an artist’s impression of a young and an adult Tyrannosaurus Rex

In their study, the researchers collected data on more than 550 dinosaur species from well-known fossil localities from across the globe.

After first organising each species by diet and mass, the team then analysed the numbers of small, medium and large dinosaurs in each community — and found a distinct pattern.

‘There is a gap,’ Ms Schroeder explained, adding: ‘Very few carnivorous dinosaurs between 100—1,000kg [200 pounds to one ton] exist in communities that have megatheropods.’

‘And the juveniles of those megatheropods fit right into that space.’

The findings, explains why carnivorous dinosaurs tended to only come in two adult sizes, small and massive (as seen in those of Alberta’s Dinosaur Park Formation, as pictured bottom), rather than a more diverse spread of proportions as seen in populations of modern-day carnivores (such as those of South Africa’s Kruger National Park, top)

The researchers also noted that the gaps they identified varied at different times — being generally smaller in communities from the Jurassic, 200–145 million years ago and larger in communities from the Cretaceous, 145–65 million years ago.

‘Jurassic megatheropods don’t change as much — the teenagers are more like the adults, which leaves more room in the community for multiple families of megatheropods as well as some smaller carnivores,’ Ms Schroeder explained.

‘The Cretaceous, on the other hand, is completely dominated by Tyrannosaurs and Abelisaurs, which change a lot as they grow.’

Young dinosaurs like T. rex tend to start off about the size of a housecat — before growing to around the size of a bus and ending up weighing in at some 1–8 tonnes, as pictured

To confirm that the ‘gaps’ were really caused by juvenile megatheropods, the team reconstructed the dinosaur communities with the teens taken into account.

They did this by combining growth rates (calculated from the tree-ring-like lines found in the cross-sections of bones) with the proportion of infant dinosaurs surviving each year based on fossil mass-death assemblages.

This enabled them to calculate what proportion of a megatheropod populations would have been made up of juveniles.

The full findings of the study were published in the journal Science.

KILLING OFF THE DINOSAURS: HOW A CITY-SIZED ASTEROID WIPED OUT 75 PER CENT OF ALL ANIMAL AND PLANT SPECIES

Around 65 million years ago non-avian dinosaurs were wiped out and more than half the world’s species were obliterated.

This mass extinction paved the way for the rise of mammals and the appearance of humans.

The Chicxulub asteroid is often cited as a potential cause of the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event.

The asteroid slammed into a shallow sea in what is now the Gulf of Mexico.

The collision released a huge dust and soot cloud that triggered global climate change, wiping out 75 per cent of all animal and plant species.

Researchers claim that the soot necessary for such a global catastrophe could only have come from a direct impact on rocks in shallow water around Mexico, which are especially rich in hydrocarbons.

Within 10 hours of the impact, a massive tsunami waved ripped through the Gulf coast, experts believe.

Around 65 million years ago non-avian dinosaurs were wiped out and more than half the world’s species were obliterated. The Chicxulub asteroid is often cited as a potential cause of the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event (stock image)

This caused earthquakes and landslides in areas as far as Argentina.

But while the waves and eruptions were The creatures living at the time were not just suffering from the waves – the heat was much worse.

While investigating the event researchers found small particles of rock and other debris that was shot into the air when the asteroid crashed.

Called spherules, these small particles covered the planet with a thick layer of soot.

Experts explain that losing the light from the sun caused a complete collapse in the aquatic system.

This is because the phytoplankton base of almost all aquatic food chains would have been eliminated.

It’s believed that the more than 180 million years of evolution that brought the world to the Cretaceous point was destroyed in less than the lifetime of a Tyrannosaurus rex, which is about 20 to 30 years.

Source: Read Full Article