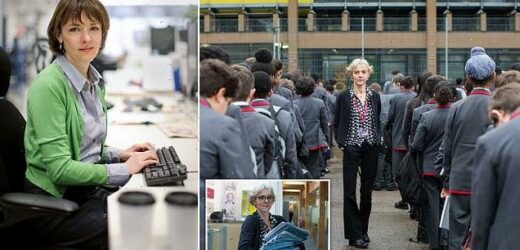

A brutal lesson in humility: At 57, LUCY KELLAWAY gave up her marriage, her home and six-figure salary as a media star to teach maths in an inner-city comprehensive. Here, she reveals the pain (and pleasure) of mid-life reinvention

- Former writer Lucy Kellaway, 61, quit journalism for teaching four years ago

- She was an FT columnist on a six-figure salary for 32 years, but traded that in for a trainee Maths teacher role at Mossbourne Community Academy, London

- She also co-founded Now Teach, an educational charity for late career changers

- Kellaway sacrificed her marriage, her home and more in her mid-life reinvention

- Now, she reveals the highs and lows of flipping her world upside down in her 50s

The date is Wednesday, August 30, 2017. It is my first day in my new job, and I’m lost.

I am 58. I’ve just become a teacher. And I have never felt so out of my depth.

In the empty school corridor, I spot someone and ask the way to the auditorium. Follow me, she says.

She breaks into a run, which I later learn is to avoid being shamed for lateness in front of the entire teaching body.

This is quite a departure from my old life, in which being on time for a meeting suggested you weren’t busy or important enough.

Then again, in my old life I once paid £680 for a Paul Smith dress.

That seems vaguely justifiable, in that I wore it to every corporate do and for every speech I gave for three years.

Former Financial Times columnist Lucy Kellaway, 61, quit journalism for teaching Maths at Mossbourne Community Academy, London four years ago

Now I look back at such expenditure with mild disapproval. Not only does it seem morally dubious to spend so much money on a scrap of wool, polyester and Spandex, but it’s more than half my take-home pay.

Another big change is lunch, which now comes in a Tupperware box that I’ve packed at 6.25am — well before I used to wake up.

Six weeks into my new life, I’ll get an email from an old contact. ‘Hi Lucy! Hope you’re well. Are you enjoying teaching? Which day is best for you to catch up over coffee or lunch?’

I’ll look at this and feel the size of the gap between my current world and my old one. The answer to the second question is easy. No day is good for a coffee or lunch.

Teachers work all day, five days a week, so lunch and coffees no longer exist. The weekend is no good either. I’m simply too tired.

The answer to the first is even easier. No, I’m not enjoying teaching.

It is not enjoyable to be out of control — to find you’ve come to the classroom without exercise books, so the whole class has to do their work on pieces of paper — and then your head of department comes in to ask what you’re doing.

‘Enjoy’ is altogether the wrong word. A better word might be ‘obsessed’.

Never have I been this engaged with anything in my professional life. I will think about nothing else from the moment I wake up pre-dawn.

My students will visit me in my sleep and are with me as I get up, wired, at 5.30am.

The utter terror of my first term

By the end of the first day as a trainee teacher, I am wet with sweat.

There are great circles under my arms and my hair is stuck to my head.

I remember some advice given by a teacher on how to survive the first term, which at the time I thought was an exaggeration.

‘Wear a jacket you hate — you’ll sweat so much it’ll never recover.’

Now I must face my 35-year-old mentor Yasmeen, who will be responsible for me and my progress.

On a sheet of A4 paper, she has drawn two columns headed WWW and EBI — ‘What Went Well’ and ‘Even Better If’.

In my previous life at the Financial Times, I would have scorned these euphemistic acronyms.

Now I must take them seriously.

What went well, it turns out, is I have a good teacher presence.

What went badly was everything else.

The EBI column contains 23 items, starting: too fast; mistake on the board; workings not clear; Jamal didn’t understand; Yunus was looking out of the window.

Tomorrow I have the same class for a double lesson and I haven’t started planning.

I stay up until 1am preparing my slides and the next day, stressed and bleary, I make more mistakes on the board.

On Friday I go for drinks with my maths colleagues.

We start drinking at 4.45pm and an hour later I’m really enjoying myself.

They are mystified as to why I would have taken a pay cut to be a teacher, but I think they are flattered that I have chosen to do what they do.

I buy another round, glowing inside at how well I’m fitting in.

But then Roisin, a 25-year-old teacher from Ireland who I’ve singled out as a future friend, turns to me and says: ‘You really remind me of my grandmother.’

Two weeks pass. The unwanted thought that I really might not be any good at teaching is starting to occur to me.

At least I’ve proved I’m good at other things. This thought is allowing my ego to hold up, just about, though no one could care less that I used to write decent columns on the FT.

The students have never even heard of it.

‘How long are you going to stick with teaching?’ asks the regular teacher of my class during a particularly bad post-mortem.

Out of nowhere comes my defiant answer: I am going to teach until I’m 75.

She looks incredulous but the more incredulous she is, the more determined I am to prove her wrong.

When I go back after half-term, the head of maths comes to observe me.

I am eager to impress and have planned a careful lesson teaching Year 7s.

The department head invites me into her office afterwards and tells me the things I know I’m bad at: careless modelling, not enough structure, too many students calling out answers.

Then she says the reason they were calling out was that they were excited and — here was the heart of the problem — I had made them excited by being excited myself.

I look at her goody-goody plait and seethe. I want to say: I fundamentally disagree with your view on education.

Anything that makes them excited is good.

And I would much rather have an exciting teacher than a boring one. More than that, I want to say: shove your job. I refuse to be a robot.

For now, I have to get a grip. ‘Thank you so much,’ I say.

‘That is really useful feedback.’ I may not be good at teaching but I am good at office politics, having built up my skill over 30 years.

This time, I am pretty sure I nailed it: I don’t think she can see the mutiny behind my eyes.

My head will be filled with the same ragged, euphoric sensation I last had when I was in love.

Two years before that, in 2015, I was living in a large, terraced family house in Highbury, North London, with a husband and four children.

My life was a model of stability.

I had been married to the same man for 25 years.

For the past 15 years I had lived in the same place, which itself was less than three miles from the large, terraced family house where I grew up.

I had worked at the same newspaper for 32 years and every Monday for more than two decades had written the same column.

Most mornings at 9.30am I would cycle to the Financial Times, where an office full of hacks, many of whom had also been there for decades, sat at their desks drinking coffee out of cardboard cups.

At the end of the day I would cycle home, where most nights I would make supper for my children, my husband and for my dad, who lived near by.

In the space of two years I tore it all down. House, marriage, job, considerable income — I dispatched the lot of them.

If there was one self-inflicted change that tipped me into ending my 32-year relationship with my employer, it was not the act of separating from my husband — it was moving into a modern house.

Possibly I would be a teacher if I still lived in our old house in Highbury, though I doubt it. Its roots were deep.

If I were still living there, I think I would still be stuck in a life that no longer suited me.

In August 2015, I left my husband David for a 20ft strip of bright orange Corian.

Not only did spending all my life savings on this coloured polymer — and the modern house that encased it — make me happier; it also helped my relationship with David, who is still technically my husband, as neither of us can see the point in divorcing.

More unexpectedly, the freedom that came from leaving the vertical Victorian houses I’d lived in all my life and moving to a horizontal modern space did something I can’t quite understand, even now. It released me from the force of habit that had defined my life until then.

During our 15 years in a big, solid family house, David and I had started to fall apart.

I don’t know why a marriage ever ends but the two of us, through years of overwork, distraction and mutual neglect, had somehow lost the thread that had once tied us to each other so securely.

The house was oblivious to our distress and doggedly continued in its role as family headquarters.

It was big enough to accommodate any dysfunction we threw at it; after our nanny moved out, David moved into the basement flat, sometimes coming up for family suppers to join his grumpy wife, his grumpy teenage children and his frail father-in-law.

The resentment that had been a growing feature of my marriage receded a little.

It gave each of us space from the other while at the same time allowing us to act as if we were still more or less a normal family.

Then one day I went to view an intriguing modern house — ‘just for fun,’ I told my daughter Maud.

It was a wooden triangle. Inside there was a big open space, with glass walls onto the garden and a long strip of orange Corian worktop running down the middle.

I stepped over the threshold and had an earth-moving coup de foudre that I’d never experienced before and haven’t since, either with bricks and mortar or with flesh and blood.

It was a yearning so powerful, I must have had an inkling that buying this house would change more than my address.

The story seemed to be this: I was going to leave my husband and the edifice of our family life, not for another man but for a glorified garden shed that cost an astounding amount of money.

Yet when I moved in, on a hot day in the middle of August 2015, my spirits were soaring.

Looking back, it was always on the cards that I’d end up a teacher.

My mother was one and my eldest daughter Rose is one and these things tend to run in families. But it took me a long time to realise that.

Mum taught English at Camden School for Girls, the famously liberal establishment that I went to in the 1970s. I admired her but I never wanted to be like her.

I looked at the piles of books she sat marking until midnight.

I watched her run herself ragged putting on a school play, getting so frazzled that at home she would bang saucepan lids and snap at us.

I also could not believe how little she earned. I wanted my work life to be as unlike Mum’s as possible.

Lucy Kellaway (pictured), 61, shared her experience of quitting her career as a columnist to become a teacher

When I left university, I got a job at J.P. Morgan. My starting salary, as a know-nothing 21-year-old, was slightly more than what Mum got as surely one of the best teachers in the borough.

Banking turned out to be grim: a lethal combination of stress and boredom.

By the age of 25 I had wangled a job at the Financial Times — and there I stayed for the next 32 years.

Twenty years into this accidental career, I had interviewed all sorts of interesting people.

The column I’d been writing for a decade had become a fixture in the paper. Then one morning in January 2006, Mum woke up early, went upstairs in her nightdress to make herself a cup of tea, had an aneurysm and died.

As I tried to march on through the torrent of shock and grief that followed, I decided I didn’t want to be a journalist any more.

If my brilliant, vibrant mother was no longer there, I needed to try to continue the work she had started.

The feeling didn’t last. I was then 47, which I decided was too old to do something so radical.

More important, I still wanted to be someone. It hadn’t occurred to me that a teacher, with the notable exception of Mum herself, was anyone at all.

For the next decade, I forgot about teaching. I went on, mainly happily, doing what I had always done.

What sustained me, as always, was a personality flaw: I was both insecure and a show-off. I wanted the limelight but also suffered from impostor syndrome.

But mostly the fear of being rubbish was manageable.

‘Most mornings at 9.30am I would cycle to the Financial Times, where an office full of hacks, many of whom had also been there for decades, sat at their desks drinking coffee out of cardboard cups’

The other thing that kept me writing was equally unattractive: I was profoundly impressed by the sight of my own name in a newspaper.

I enjoyed the way strangers’ faces would rearrange themselves when I announced that I worked for the FT.

Status really mattered to me. I wanted to be seen to be successful.

I thought I wouldn’t be invited to things and people wouldn’t be interested in talking to me if I didn’t have the badge of an FT columnist.

But sometime after my 50th birthday, my job started to pall on me. I no longer felt sick every time I’d finished writing something. Instead I would file a column and shrug, usually thinking: not great but it’ll probably do.

At the same time as losing my fear, something else was unravelling: my preoccupation with status.

I was no longer impressed that I worked at the FT and didn’t expect anyone else to be. The doors my job opened to me were ones I no longer wanted to pass through.

The penny had taken almost two decades to drop, but I’d worked out that those parties I needed an FT badge to get invited to were ones I’d never enjoyed going to.

Despite all this, I kept going. The freedom suited me, as it always had.

Being a columnist in charge of your own time was a gift when the children were young and went on being a gift when my father was old.

Then in early May 2016, he died.

Three days later I went back to work — because it was what Dad himself would have done. He didn’t like a fuss and thought it was important to get on with life.

All around me, my colleagues were looking busy and important. I scrolled through the news and a thought presented itself to me. I can’t do this any more.

As I entertained the idea, it grew to fill my whole head. I had to get out. But what could I do? I was 57 and had spent almost my whole adult life doing one thing.

‘I remember looking at him sitting complacently in his chair in his office with its view of the Thames and thinking: you may be happy in your gilded cage but the door of mine has unexpectedly sprung open’

I don’t think I was especially depressed; I was just unhappy and monumentally stuck.

I had been doing the same thing for too long and was worn out mentally, physically and emotionally. What on earth was I going to do with all the time I had left?

In the week after Dad died, I found myself thinking of the shortage of teachers and rang the Government’s helpline.

Me: I’m 57 and am thinking of becoming a teacher. Am I too old? Man on the telephone: No, there’s no maximum age.

I told him I wanted to teach maths. I had no desire to be an English teacher like Mum — a lifetime of writing meant I’d had it with words.

What I felt I wanted was the certainty of numbers, and maths was my favourite subject at school.

It was a decision taken lightly, considering I last did maths in 1977 and only got a B at A-level.

The man on the phone assured me I could teach maths without a degree in it. I hung up feeling light-headed.

Maybe I’ll actually do this, I thought. In the next few weeks, I tried the idea out on everyone I met. Half thought it a splendid plan, half did not.

Gideon Rachman, my friend and fellow columnist at the FT, leaned back in his chair and laughed.

‘Let me get this straight,’ he said. ‘You’d be leaving a job that is well paid, that you’re good at, that is glamorous and flexible — for something badly paid with low status that you’d probably be rubbish at.’

I remember looking at him sitting complacently in his chair in his office with its view of the Thames and thinking: you may be happy in your gilded cage but the door of mine has unexpectedly sprung open.

In November 2016, I wrote a column telling readers I was quitting the following summer.

The morning before my story was due to appear, I was scooped on my own news by another newspaper.

I read the article — and started to cry. It was as if, in the frantic excitement of preparing for my new working life, it hadn’t occurred to me I was actually leaving my old one.

I stood by my orange counter in my dressing gown, convulsed in sobs. I’d done something irrevocable. As I howled, I read the story and then the comments underneath.

The first said: ‘A loathsome PR stunt from a patronising corporate class. Teaching is not like running an artisan bakery in Shoreditch.’

The second: ‘Good luck. Journalism into teaching. What could possibly go wrong? I look forward to her article “Why I left teaching” in two years.’

I stopped crying at once. Damn you, I thought, pulling myself together. I will show you.

Not all the comments were quite so hostile but everyone agreed on one thing: this woman does not know what she’s letting herself in for. On that point, at least, they could not have been more right.

Source: Read Full Article