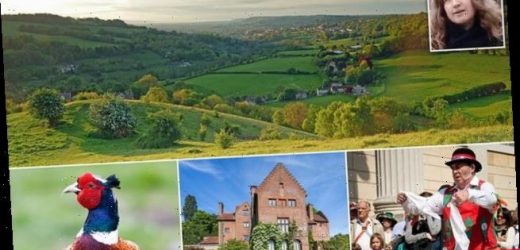

Does this look ‘unpleasant’? Academic signed up by the National Trust to lecture us on the evils behind our most glorious estates says GARDENING has its roots in racial injustice

- Professor of Post-Colonial Literature at University of Leicester, published work examining links between British countryside, racism, slavery and colonial past

- Claimed cherished national pastime of gardening had roots in racial injustic

- At the centre of the ‘culture war’ within National Trust after ‘outed’ many of the properties belonging for their links to slavery and Britain’s colonial past.

We are living in stressful times: no wonder so many of us have taken refuge in our gardens and in the quiet corners of our potting sheds.

Can there be a more harmless, innocent diversion than gardening? We all know it’s good for body and soul and our mental health.

But the green-fingered ranks of Britain’s gardeners are in for a shock — according to a new book, by pruning our roses or digging the vegetable patches, we are all somehow perpetuating the evils of racism.

Last week Corinne Fowler, Professor of Post-Colonial Literature at the University of Leicester, published a sprawling 316-page work examining the links between the British countryside, racism, slavery and our colonial past.

Among her startling conclusions? Our cherished national pastime, gardening, has its roots in racial injustice.

Should we be surprised? Perhaps not. The book’s title, Green Unpleasant Land, gives us an indication of Professor Fowler’s thoughts on the countryside.

One might expect her writings to be consigned to academic obscurity. But her views on rural Britain are in fact very influential.

For she is at the centre of the ‘culture war’ that has overwhelmed one of Britain’s largest and best-loved charities, the National Trust.

Last week Corinne Fowler, Professor of Post-Colonial Literature at the University of Leicester, published a sprawling 316-page work examining the links between the British countryside, racism, slavery and our colonial past

Professor Fowler is one of the principal authors of a 115-page report published in September last year that ‘outed’ many of the properties belonging to the Trust for their links to slavery and Britain’s colonial past.

Among them were Buckland Abbey, the Devon seat of Sir Francis Drake, Ham House in West London, Wales’s Powis Castle and, most controversially, Chartwell, the family home of Sir Winston Churchill.

The report infuriated not only grand families who bequeathed their homes to the Trust, but also many of the charity’s 5.6 million members who resigned over this ‘woke’ agenda, arguing that the Trust’s role is to preserve our ancient houses and monuments, rather than get involved in what many saw as a highly political witch-hunt.

Such was the anger that the head of the Charities Commission suggested the National Trust should focus on looking after stately homes — not waging ‘broader political struggles’.

Yet the Trust had already ‘doubled-down’ in its determination to exhume the unsavoury history of its properties with another project, which started in 2018 — and Professor Fowler was in charge of it.

She describes the scheme — Colonial Countryside: National Trust Houses Reinterpreted — on the Leicester University website as ‘a child-led history and writing project which seeks to make historic houses’ connections to the East India Company and transatlantic slavery widely known’.

Should we be surprised? Perhaps not. The book’s title, Green Unpleasant Land, gives us an indication of Professor Fowler’s (pictured) thoughts on the countryside.

It involves a team of historians working with 100 primary school children to explore these links at 11 Trust properties and received lottery grants amounting to £160,000. This week, it emerged that under the scheme, the Trust had been inviting teams of children to lecture staff and volunteers, presumably about the evils of colonialism.

Amid criticism of the project last month from MPs — one of whom complained the charity had been ‘overtaken by divisive Black Lives Matters supporters’ — the Trust defended it, saying: ‘We always look for excellence, fairness and balance in the assessment of all aspects of the history at National Trust places, often working with external partners and specialists to help us.’

But just how fair and balanced are Professor Fowler and her team of academics? Are they impartial historians — or is there a political agenda behind their interpretations of the past?

For an answer we must first examine Professor Fowler’s new book in greater detail, a book which is hardly likely to be a best-seller among National Trust members — its publishers say it ‘should make uncomfortable reading for anyone who wants to uphold nostalgic views of rural England’.

Professor Fowler insists that our ‘green and pleasant land’, as the poet William Blake put it, is anything but. Our countryside, she suggests, is a hotbed of oppression, racism and exploitation — and it is time for its dark history to be exposed.

Intriguingly, Fowler acknowledges that her own family had long-standing connections to slavery and colonialism, through sugar plantations in the Caribbean. As she says in the book on this issue: ‘I make no claim to neutrality . . . Our relatives either profited from empire, or were impoverished by it.’

The professor also writes that her parents gave her a love of country walking.

She appears to have rambled tirelessly along country lanes finding evidence to prove her central premise — that the British countryside is linked inexorably to racism and colonialism.

Morris dancing is another source of controversy. ‘The face-blackening practised by the dancers has become a potent symbol of rural racism.’ And, to be fair, many Morris dancing groups have now abandoned the practice

‘The countryside is a terrain of inequalities,’ she writes, ‘so it should not surprise us that it should be seen as a place of particular hostility to those who are seen as not to belong, principally black and Asian Britons.’

Many great estates were financed by slavery and colonialism, and the origins of gardening were fundamentally elitist: ‘Knowledge about gardens and plants, in particular botany, has had deep colonial resonances,’ she says.

‘The scientific categorisation of plants has at times engaged in the same hierarchies of “race” that justified empire and slave and slavery . . .

‘Inevitably, then,’ she adds, ‘gardens are matters of class and privilege.’

Racism is ingrained not just in gardening, she believes, but in many of our rural traditions. She cites as an example our nation’s approach to that symbol of rural Britain, the pheasant.

She says that the bird’s heritage has effectively been hijacked by the indigenous white population. We are all in denial, apparently, about its Asian origins.

‘This bird,’ she writes, ‘is habitually represented as native to England’s fields, hedgerows and woodlands . . .’ But, she stresses, it ‘is a global not a local bird’. A clear case of cultural appropriation.

Morris dancing is another source of controversy. ‘The face-blackening practised by the dancers has become a potent symbol of rural racism.’ And, to be fair, many Morris dancing groups have now abandoned the practice.

She is unimpressed by former Tory Prime Minister John Major’s evocative prediction in 1993 that ‘50 years from now, Britain will still be the country of long shadows on county grounds, warm beer, invincible green suburbs, dog lovers and — as George Orwell said — old maids bicycling to Holy Communion through the morning mist.’ ‘Rural Britain,’ she counters dismissively ‘. . . is rarely peaceful. The elderliness of the maids is incongruous with the many itinerant female East Europeans who, before Brexit, picked the fruit and vegetables that grace our tables.’

And there is more, much more, in the same vein running through her book.

As she says, she makes no claim to neutrality.

Professor Fowler is one of the principal authors of a 115-page report published in September last year that ‘outed’ many of the properties belonging to the Trust for their links to slavery and Britain’s colonial past

The Colonial Countryside project was commissioned by the Trust in 2018, but became a political hot potato in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement last summer and the toppling of the statue of the slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol.

In a recent interview, Professor Fowler appeared untroubled by the vandalism, which has seen four people charged with criminal damage and who are due to appear in court later this month.

‘I think it can be a watershed moment,’ she opined. ‘The important thing is to tell the stories which are central and relevant to understanding these historic houses. If that makes it uncomfortable, then so be it. It’s not all about cream tea.’ Little wonder that, in her book, Professor Fowler takes aim at TV productions such as Downton Abbey for glossing over the global history of great country houses.

But what of her fellow academics on the Colonial Countryside project? Among them is Raj Pal, a historian who uses the Twitter name ‘Raj Pal “damn black”’.

Last month, Mr Pal referred to Boris Johnson and members of the cabinet, including Dominic Raab and Michael Gove, as a ‘shower of s****’.

He went on to call for those who vandalised the Edward Colston statue, causing thousands of pounds’ worth of damage, to receive an ‘award for advancing knowledge & understanding of the past’.

Racism is ingrained not just in gardening, she believes, but in many of our rural traditions. She cites as an example our nation’s approach to that symbol of rural Britain, the pheasant

Also on the team is ‘Heritage Consultant’ Dr Marian Gwyn. She was a signatory to a letter objecting to the new Museum of Military Medicine in Cardiff which, after a long planning battle, has been granted permission for a new site in Tiger Bay.

In the joint letter to Cardiff City Council, she called the museum ‘effectively a monument to the British Empire and its armed forces,’ adding: ‘To confront our imperial past and past conflicts is one thing, to try to use it as an attraction in such a location is an affront . . .’

Jason Semmens, the Museum’s Director, was unimpressed, telling the Mail: ‘The Museum of Military Medicine is not a monument to the British Empire, nor does it glorify its colonial past.

‘Our exhibitions recognise the innovative work of Florence Nightingale, who reformed nursing and public health; John Hall-Edwards, who pioneered the use of X-rays in surgery in the 1890s; and Geoffrey Keynes, whose discovery that blood can be stored by adding sodium citrate led to the creation of blood banks, all of which have gone on to save millions of lives globally.’

Another academic involved in the Colonial Countryside project is Dr Katie Donington, who is based at London South Bank University. On Twitter she said: ‘The toppling of the statue of the slave trader Edward Colston is not re-writing history. It is not destroying history. It is making history.’

Yet, despite these pronounced political leanings among the academics working on Colonial Countryside, the Trust is convinced of the integrity of the project.

A Trust spokesman explains that those who work with the charity do so under ‘strict political impartiality guidelines’.

Yet many are unhappy at what they perceive as the Trust’s increasingly ‘woke’ agenda, particularly at a time when properties are being mothballed and revenue has collapsed because of Covid.

There is currently a £200 million black hole in the charity’s accounts and hundreds of staff have been made redundant, yet the Trust managed to find the funds for last September’s report on links to slavery and colonialism out of its own resources.

Among the disenchanted is Nigel Biggar, Oxford University’s Regius Professor of Moral and Pastoral Theology. He is involved in a five-year project on Empire And Ethics and has called for a reappraisal of our colonial past.

Professor Biggar insists that the history of the British empire was ‘morally mixed’ — some bad and some good — and has been accused of racism for failing to toe the line that the empire was uniformly evil.

‘The National Trust has shot itself in the foot,’ he told me. ‘It has really got a lot of its members annoyed. I am one of them.

‘I’m annoyed not because it wants to conduct historical research, but because it seems to have swallowed a political position uncritically.

‘The research it’s conducting is serving a particular political purpose with which lots of us in the National Trust disagree and with good reason. The key question is: What motivates people like Professor Fowler to apparently see racism everywhere, even when it isn’t there?’ Sir John Hayes, leader of the Common Sense Group of Conservative MPs, which has been highly critical of the Trust, told the Mail: ‘The National Trust’s charitable purpose is being stretched to its breaking point. The fact is the National Trust is losing large amounts of money at the moment, and sacking staff while spending time, money and energy on this nonsense.’

Sir Roy Strong, the architectural historian and former director of the Victoria and Albert Museum and the National Portrait Gallery agreed, saying the National Trust has gone ‘completely bonkers . . .

‘It’s all about wokery. I think the Trust finds itself subscribing to a skewed view of history and applying it to the past.

‘I feel quite disturbed at these major changes taking place in a year when [because of the pandemic] the Trust hasn’t been able to hold a proper Annual General Meeting.’

Professor Fowler is upset by her critics, saying in an interview that she was being ‘intimidated’ by them. It is a complaint given short shrift by former Cabinet minister Lord (Peter) Lilley.

‘If anyone has intimidated, threatened or abused Professor Fowler, as she claims, I would leap to her defence. But to imply that the Common Sense Group has done so is absurd. We simply criticised her ideas.

‘If she cannot take criticism she should not be in the university, let alone lecturing the nation. Arguably, it is she who has insulted her country by her book whose very title — Green Unpleasant Land — tells us what she thinks of her fellow citizens.’

The next year will be crucial for the Trust, and already Director-General Hilary McGrady is making conciliatory gestures to members who feel that some factions within the Trust have gone too far in trying to pursue their politically correct agenda.

I am told by a source close to the Trust that embattled Ms McGrady is personally exhausted by these wars — and wants to move the Trust on.

The question is whether the zealots, the professional racism-auditors and academics such as Professor Fowler, will allow her to do so.

‘At the end of the day,’ says Sir John Hayes, ‘I’d be happy to sit down with the National Trust, to see how they can get out of this mess. But it is a mess of their own making, and it has to be resolved in a way that, frankly, encourages them to recognise the offence they have caused — and to return to what they ought to be doing.’

In the meantime, perhaps the rest of us should retreat to our rhododendron bushes — or take cover behind the privet hedges. Whether we like it or not, this particular war will be a long one.

Source: Read Full Article