The bonkers baron whose life was a pursuit of hedonism: He inspired the wildest character in the BBC’s new drama, but from dyed doves and dogs in pearls to riotous parties, Lord Berners was even barmier, writes ALISON BOSHOFF

- The 14th Baron of Berners was a true bon vivant of the early 20th century who entertained everyone from Salvador Dali to Evelyn Waugh

- He made such an impression on Nancy Mitford that she based Lord Merlin, the outrageous aesthete in her 1945 novel The Pursuit Of Love on him

- Berners adored pranks and practical jokes, and once even placed an advertisement in The Times newspaper offering two elephants for sale

- Despite his wealth, he detested pomposity and did his best to poke fun at the upper classes

Has there ever been a more eccentric British peer?

His dogs wore pearl necklaces, he dyed his flock of doves in all shades of the rainbow, suggesting neighbouring farmers might like to do the same with their cattle, and kept a pet giraffe at his Oxfordshire country estate, Faringdon House.

There — where he lived with his lover ‘Mad Boy’ — he erected a 140 ft folly with a sign at the bottom which read: ‘Members of the public committing suicide from this tower do so at their own risk.’

Despite his enormous wealth, the 14th Baron Berners detested pomposity and did his best to poke fun at the upper classes —delighting in silly pranks played on society darlings and politicians alike.

He is even said to have terrified his neighbours by wearing a pig mask when behind the wheel of his Rolls-Royce, which was customised with silk hangings of birds and a portable clavichord under the driver’s seat.

A true bon vivant of the early 20th century, Berners entertained everyone from Evelyn Waugh to Cecil Beaton, Salvador Dali and, notably, Nancy Mitford.

In fact, he left such a lasting impression on Mitford that he inspired the outrageous aesthete, Lord Merlin, in her 1945 novel The Pursuit Of Love — brought to life on Sunday night in the first instalment of the BBC’s new three-part TV adaptation.

And of course, Lord Merlin, played by Fleabag’s Andrew Scott, is the undoubted star of the show. Unapologetically over the top, Merlin sweeps Linda Radlett (Lily James) away from her failing marriage for a whirl of dancing and opulent parties — even gifting her a Renoir painting and a house in London’s Chelsea.

But, as glorious as Lord Merlin is, his real-life inspiration was arguably even more wonderfully bonkers. And because everyone was captivated by Berners’ capacity for extravagance, everyone who was anyone wanted to come to his parties.

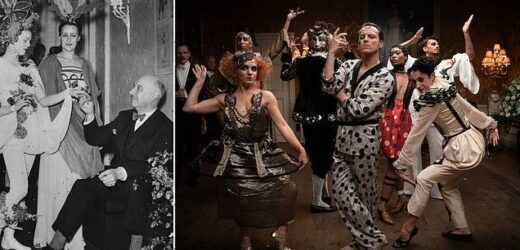

Andrew Scott (centre) as Lord Merlin in The BBC’s The Pursuit of Love. His character was inspired by the outrageous aristocrat the 14th Baron of Berners

Photographer Cecil Beaton was a regular guest at Faringdon and took hundreds of photographs of Berners’ famous set.

One of them shows Penelope Betjeman, wife of poet laureate John, madly serving tea to her white Arab horse Moti inside the drawing room. Meanwhile, Dali played piano in the ornamental lake.

The Mitfords loved extended periods of escapist entertainment at the house during the Blitz, and other noted visitors included critic Cyril Connolly, and writers Gertrude Stein, André Gide and H.G. Wells.

Another of his guests was the Marchesa Luisa Casati, who kept a pair of pet cheetahs at her palazzo by the Grand Canal in Venice and was reputed to have dipped her black servants in gold paint.

When she stayed at Faringdon, she brought a boa constrictor in a glass case. ‘Would it like something to eat?’ Berners’ mother asked. ‘No,’ the Marchesa replied, ‘it had a goat this morning.’

Ever the trickster, Berners once sent an invitation to notorious social climber Sibyl Colefax that ran: ‘I wonder if by any chance you are free to dine tomorrow night? It is only a tiny party for Winston [Churchill] and GBS [George Bernard Shaw].’ But Berners made both his name and the address on the envelope illegible.

He adored pranks and practical jokes, and once even placed an advertisement in The Times newspaper offering two elephants for sale.

When telephoned by the paper about the ad, he jibed that he had sold one to the politician Harold Nicolson.

Travel writer Patrick Leigh Fermor recalled that there were paper flowers in Berners’ gardens and that the Faringdon house was replete with joke notices. Leigh Fermor recalled ‘No dogs admitted’ at the top of the stairs, and ‘Prepare to meet thy God’ painted inside a wardrobe.

‘When people complimented him on his delicious peaches he would say: ‘Yes, they are ham-fed.’ And he used to put Woolworth pearl necklaces round his dogs’ necks —and when a guest, rather perturbed, ran up saying ‘Fido has lost his necklace’, G said, ‘Oh dear, I’ll have to get another out of the safe,’ ‘ Fermor said.

Such was the allure of Berners’ surreal fantasy land, socialite Doris Delevingne is said to have attempted to seduce the gay Cecil Beaton at Faringdon, telling him: ‘There is no such thing as an impotent man, only an incompetent woman.’

She had already dallied with both Winston and Randolph Churchill and saw Beaton’s sexuality as no great obstacle.

Berners’ vast fortune was never foreseen when he was born Gerald Tyrwhitt-Wilson in 1883, an only child whose father was a largely absent naval officer, while his mother was distant and domineering. From a young age, it was clear that he was different.

One unfortunate nanny was sent packing after he booby-trapped the privy. In his memoir, First Childhood, Berners recalled that, after hearing you could teach a dog to swim by throwing it into water, he threw his mother’s dog out of the window to teach it to fly. Luckily, the dog survived.

It seems that eccentricity ran in the family, for his grandfather was said to have cursed incessantly —once even halting a church service because his language was so offensive — and, according to Berners, would spend all day in a darkened room.

In 1899 Berners joined the diplomatic service (despite failing the entry exams twice) and spent happy years on the Continent, taking music lessons from Stravinsky in his spare time.

He was a talented musician, although he didn’t pursue his art seriously, once admitting he would have been a better composer had he accepted fewer lunch invitations. But he did manage to write five ballet scores and an opera, and even composed the score for the 1947 film The Life And Adventures Of Nicholas Nickleby.

Berners (left) approves costumes for his ballet ‘Cupid and Psyche’ at Sadler’s Wells in London in 1939

Berners’ life changed when, at 35, he inherited his title, as well as vast wealth and property, from an uncle. The inheritance included the 12-bedroom Faringdon House, built in 1785 — with its crenellated swimming pool guarded by stone wyverns and with a Gothic changing pavilion paved with old pennie. He initially gave the property to his mother and her second husband. It was not until their deaths in 1931 that he moved into the house himself.

The House of Lords didn’t interest him at all. He attended just once, after which he said that he would not go back because a bishop had stolen his umbrella.

He enjoyed long jaunts across the Channel, and would often take a fortnight to travel between London and Rome (where he owned property), getting his chauffeur to stop off at the Ritz in Paris.

In the 1930s, and because of his eccentricity and wealth, Berners was becoming something of a minor celebrity in upper-class Britain. But, being rather unattractive, with a portly figure and sallow complexion, he had few romantic encounters.

However, in 1932 he met Robert Heber-Percy (his ‘Mad Boy’), the fourth son of a Shropshire squire, who was 28 years his junior — it was an instant attraction.

Heber-Percy moved to Faringdon as his live-in boyfriend, and in the house’s 1930s heyday, the pair hosted lavish parties for the rich and famous.

Berners spent his days painting, writing and composing while Mad Boy could be found swimming or riding — often naked.

The estate’s folly was erected by a devoted Berners to mark Mad Boy’s 24th birthday.

Heber-Percy had always partnered both men and women, but there was some surprise when he married the cocoa heiress Jennifer Fry, in 1942, who was pregnant (although whether the child was his remains an open question).

For a time all three lived together in Faringdon, but Fry left with the baby two years later and Heber-Percy and Berners’ companionship continued.

Only after Berners died in 1950 aged 66, leaving the Faringdon estate to Heber-Percy, was his typically devilish treatment of the family portrait collection discovered — he had put moustaches on all of the paintings, and overpainted all of the women so that their clothes appeared to be slashed to the navel.

He was jolly to the last and the doctor who attended him in his final weeks refused to charge him for his services, saying his company was payment enough.

And in a final act of fitting eccentricity, Berners wrote his own epitaph, which rather aptly runs: ‘Here lies Lord Berners, one of the learners. His great love of learning may earn him a burning — but praise the Lord! He seldom was bored.’

Source: Read Full Article