By Jordan Baker

Peter Cosgrove was 27 years old when Cyclone Tracy flattened Darwin on Christmas morning in 1974. Within days of the disaster, the government began loading shell shocked survivors onto aircraft and flying them to cities across Australia. They crouched in the aisles of the planes, and sat on each others’ laps. The young soldier, who already had a military cross from Vietnam and would go on to be governor-general, met their buses at a barracks on Sydney’s south head, where they could finally shower, eat, and sleep.

“They were destitute and devastated,” Sir Peter remembers. “Psychologically traumatised. They were absolutely down and out, tired beyond belief having left everything they owned, which was either blown away or saturated and ruined by the torrential rain.”

No one outside Darwin knew about the cyclone until Christmas afternoon, as communications were wiped out. But as soon as contact was made, the newly formed National Emergency Operations Centre swung into action, sending navy ships and organising the biggest air evacuation in Australian history – more than 30,000 people – which was underway within two days. Prime Minister Gough Whitlam flew from Europe to tour the city on December 29.

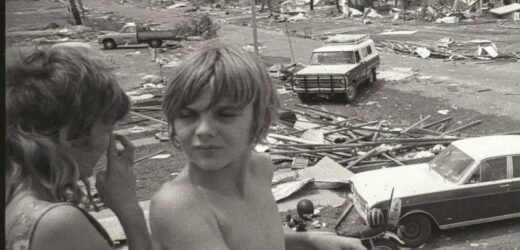

Children look on as people inspect the damage from Cyclone Tracy, which hit Darwin in 1974.Credit:Rick Stevens

Sir Peter was one of the first soldiers sent to Darwin to begin the cleanup. He remembers flying over the city and seeing complete devastation. “It reminded me of aerial images of those Japanese cities in the war [Hiroshima and Nagasaki],” he said. “Seven weeks later, we were [replaced by more soldiers]. We’d been working flat out. As we were flying out of the place in a charter jet and looked out of the window again, I couldn’t see any difference.”

As residents of the Northern Rivers region sifted through their sodden houses this week, angry that help, particularly from the Australian Defence Force, did not come sooner, some wondered whether their experience was Australia’s version of Hurricane Katrina. That storm hit the east coast of the United States in 2005 and led to a flooding catastrophe in New Orleans that exposed a litany of failures by government, including an inability to get food and water to evacuation centres.

But some, including Lismore’s mayor Steve Krieg, looked back further to Cyclone Tracy, noting not only the government’s faster response in the immediate aftermath of Darwin’s crisis 50 years ago, but also what it did next.

Tracy produced stronger and longer cyclonic winds than anyone thought possible. It killed 71 people. Sixty per cent of houses in Darwin were beyond repair. The federal government – which owned many of them – knew the city had to be sturdier, so it commissioned scientists to develop more rigorous building codes. The changes were radical, but the national dismay at Darwin’s devastation reduced opposition. Those codes have spared countless buildings across northern Australia from storms as strong as Tracy.

A report in the Herald from December 29, 1974. Credit:

The question Australia is facing is whether, some 50 years later, the country is still capable of such a bold response.

The Northern Rivers region floods regularly; residents are used to it. “It’s the most flood-affected community in the nation,” says Ballina mayor Sharon Cadwallader. In heavy rain, water flows down hills into creeks and rivers, then spreads across the floodplain. Until now, the worst on record in Lismore was in 1954, when the water reached 12.27 metres. This year was 14.40 metres. It was described as unprecedented and unimaginable, yet Lismore’s 2014 Floodplain Risk Management Plan envisaged worse. It predicted a “probable maximum flood (PMF)” level – or worst-case scenario – of 16 metres. Given climate change, the plan said, that was likely an underestimate.

Premier Dominic Perrottet, who has spent much of the past week visiting the region and speaking to victims, described the northern rivers floods as a one in 1000-year event. Politicians’ fondness for that type of statistic annoys Yetta Gurtner from the Centre for Disaster Studies at James Cook University. “I can’t tell you how frustrated I get,” she says. “They are statistical measures … they’re used by planners and insurance. [A one-in-100 year event is] one in 100 chances in any given year. You have a 3.65 per cent chance of it happening [each year]. People are getting a false perception. They think they won’t see another in their lifetime.”

They almost certainly will. Natural disasters have increased five-fold over the past 50 years, and the worst of them have featured water. A United Nations report found the deadliest events around the world over that period were droughts, storms and floods, while the costliest were storms and floods. More water vapour in the atmosphere exacerbates extreme rainfall and flooding, which Sydney saw this week. Between 1970 and 2021, 45 per cent of almost 1500 disasters in the south-west Pacific – including Australia – have involved floods, and 71 per cent of deaths were in storms.

Water began rising in northern NSW on the night of Sunday, February 27. Within two days, thousands of people who live within the 200-kilometre stretch from Grafton to Murwillumbah were affected. Along the Old Pacific Highway and up to Lismore, entire communities were underwater.

Mostly, neighbours saved each other. Desperate people relied on family or makeshift evacuation centres. Some, tired of sleeping on the floor among hundreds of others with limited resources, returned to stay in their mouldy homes. Some had nothing but the clothes they wore when they fled. “It’s hard to explain what’s going on to friends in Sydney,” says David Glendenning, a local GP. “The supermarkets are gone. There’s no Kmart, no Bunnings. No mechanics – you can’t get a tyre fixed. The postal distribution warehouse is gone. The two things we’re dealing with now, is the mental health and trauma for the whole town.”

Gail and Bill Ferrier have lived in their Woodburn home since 1973. They returned to sleep at the flooded property after a few nights in the evacuation centre. A volunteer said they had to leave this week as mould was beginning to grow. Like many in the area, they don’t have flood insurance.Credit:Janie Barrett

After a week, homes were still sodden. Communication was not yet fully restored, and many people did not know if or when help was coming. Most had not yet seen anyone in uniform. Food and water came from volunteers who spent days driving around the northern rivers or from restaurants that shut their kitchens to feed their neighbours. Even local emergency personnel on the ground were unsure about how relief was being co-ordinated at the top.

A sense of abandonment has festered. Residents are deeply distressed. “We’re going through the five stages of grief now,” says Cadwallader. “People are getting angry. The initial shock is starting to wear off. They need support through this whole process, with the grieving, the dislocation.”

There is still confusion over why the response was so slow. The role of a new government agency, Resilience NSW – set up after Black Summer – was unclear. Many say the army took too long to arrive, but there is still a question over whether that was due to delays on the state side in requesting soldiers for specific tasks – which it must do, as without invitation it’s invasion – or the federal side in sending them (there was no such problem during Tracy; the Commonwealth all but ran Darwin). Many are also asking whether the state’s existing emergency services are adequate, if it took surfers on jetskis and recreational boaters to rescue people.

But emergency management experts warn expectations of government authorities in a disaster can be unrealistic. It’s difficult, for example, to summon dozens of extra rescue boats to a flood-hit area quickly, especially if there are other floods nearby, such as in Brisbane. “It’s impossible to have the resources on hand for every particular event,” says Associate Professor Michael Eburn, an expert on legal aspects of emergency response at the Australian National University. “In a disaster, there’s a limit to what emergency services can do. By definition, what makes a disaster a disaster is we’re overwhelmed.”

Waves of destruction: the shops along the main street of Woodburn.Credit:Janie Barrett

Dr Gurtner agrees. “First responders are the community supported by the emergency services that are available,” she says. “We have an unrealistic expectation that we’ll have communications, that we’ll have electricity back in three days.”

She says education and preparation are not given enough attention. Residents of vulnerable areas – and that’s a significant proportion of Australia’s coast – should, for example, have a transistor radio, with spare batteries. They should have stores of water and food to last them weeks. They should have a pre-packed bag to grab quickly, and keep valuables – particularly photos – in waterproof containers.

And, in a disaster, they should be prepared to muck in. They did just that this week in the northern rivers, when community volunteers organised around 400 evacuations and air drops using at least 15 privately funded helicopters, and did tens of thousands of rescues with tinnies and four-wheel drives, locals volunteers said. “Volunteers are probably our greatest resource in a response and recovery capacity,” Gurtner says. “No matter how big a government is, you’re never going to have sufficient people on standby twiddling their thumbs.”

More effort should be made to prepare communities for their role, says Andrew Gissing from Risk Frontiers. Local authorities should work with local groups and businesses, so that when disaster does strike, those people are prepared. For example, if boaters are a de-facto rescue force, they could be trained in how to deal with live powerlines in floodwaters, and supplied with government-funded equipment, so next time they can do it more safely. Governments could pre-negotiate emergency contracts with private helicopter and aircraft companies.

“It would be great to recognise the role of community in disaster management more, that they do have a defined role, that they are funded to deliver disaster management approaches,” Gissing says. “It’s all about the relationships you build before an event.”

Another big question is the role of the military. Defence force personnel are being called to disaster recovery more frequently. They helped in the Black Summer bushfires, the COVID-19 response, and now in the floods. They are a trained and easily summoned labour force, but shovelling mud is a distraction from their main job, which is to defend Australia’s sovereignty.

Roger and Robyne Wood in the community radio station they run in Woodburn. Roger says the week’s disaster was “beyond government”. “No one should blame anyone. Except those that don’t believe in climate change. This is climate change. And there’s tens of thousands of people with nowhere to live.”Credit:Janie Barrett

Some argue a new military capability is required. The Australian Strategic Policy Institute has suggested a semi-civilian unit that is trained in disaster response. Former ADF chief Chris Barrie suggested rewarding volunteer service with a lifetime tax deduction.

Sir Peter thinks states should develop, and the Commonwealth fund, a civilian emergency-response force akin to the army reserve. They would be trained in disaster relief skills, which they would hone at weekly meetings and at regular camps. They would, like army reservists, be paid for their time. Importantly, they would be on standby to mobilise immediately. “They are trained because they are going to take on hazardous work, they are skilled, equipped, and they are readily available at a drop of the hat,” he says.

The other issue facing flood-ravaged communities, and the governments that serve them, is what happens next. It’s just five years since the last bad floods in the northern rivers. More will come.

The decisions made after Cyclone Tracy saved countless buildings across northern Australia. Now, few people die when category 5 cyclones hit populated areas. But there’s a difference between wind and water; the latter is harder to repel. “Unless you move houses, it’s hard to completely mitigate the risk,” says Matthew Mason, from the school of civil engineering at the University of Queensland, who wrote a paper on lessons from Tracy for the now-defunct National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility (NCCARF).

Sir Peter Cosgrove surveys damage after Cyclone Larry in Queensland in 2006.Credit:AAP

There are ways to mitigate the impact of floods, such as building levees and raising roads so there’s an evacuation route. Councils can require new houses to be built higher than the predicted water levels, but that’s expensive and doesn’t fix the problem of older houses. It’s also an inexact science, if flood levels keep rising to unprecedented levels.

Before the latest disaster, Ballina council introduced a rule that houses had to be lifted 2.5 metres. They also had to be solid rather than on stilts, as too many people turn the underside of an elevated house into an extra room. There was strong resistance to the decision, says Cadwallader, because of the cost. She anxiously watched floodwaters rise last week, praying they wouldn’t get to 2.5 metres. “It was hair-raising,” she says. They reached 2.3. The houses built to council specifications were spared.

The Nothern Rivers was inundated with water and locals have begun the enormous clean-up process.Credit:Janie Barrett

The evacuation of Darwin was traumatic, but it gave authorities time to plan how to rebuild. The Commonwealth also owned most of the housing, so it could decide how to rebuild it. In the Northern Rivers, residents urgently need somewhere to live. The easiest and cheapest option will be to rebuild as before, particularly if insurance companies fund only an identical structure, and not the extra cost of flood mitigation. “One response would be to say if the house is a write-off, don’t allow people to build back, but then you’ve got to find 2000 homes for people, which is not an easy thing to do,” says Mason.

Many people in the region also live from paycheck to paycheck. “Finance is one of those big inhibitors in terms of disaster management,” says Gurtner. “[Residents] have to make that choice. Am I willing to live with the risk and the cost? Or do I reconsider where I live?”

Another option is moving smaller towns. In 2011, floods ripped through Grantham in Queensland, killing a dozen people. The council bought higher land from a grazier, and it was divided into lots, which were given out in a lottery. The federal and state governments contributed about $18 million to the project. Those who moved still required money to build a house (some relocated their old one), and some didn’t want to leave their homes. Now, about 80 families live at New Grantham. When floods ripped through the valley again this year, the higher houses were spared.

“This is a conversation we need to have,” says Mason. “It’s not an easy one, and possibly the solutions are not palatable to residents, but to really reduce the risk, some pretty hard decisions have to be made … or the same thing is just going to happen again.

“There was a lot of talk after the 2011 floods in Brisbane, but as far as I can tell, few things have changed. As with many disasters, you get a really short period of time afterwards – ‘let’s make this big change and it could work’ … because even a month or two later, another thing has come up and the opportunity has gone.”

Sir Peter led the recovery efforts after Cyclone Larry, which struck north Queensland in 2006 and was the most violent storm in almost 100 years. He was installed at headquarters in Innisfail within three days of the storm being downgraded. “My message was don’t worry, we’ll get things back better than ever,” he says.“And we did. [Cyclone Tracy was also] a terrible thing, but the response was Phoenix-like.”

With Natassia Chrysanthos

Amid more frequent and intense disasters, “hard decisions have to be made”

Most Viewed in National

Source: Read Full Article