Singapore: Australian cattle farmers and abattoirs lost half a billion in exports to China in the last two years, cotton producers were down $870 million, copper exporters $1.5 billion.

But the Chinese importers did not miss those products. Australia’s great Indo-Pacific ally, the United States, was happy to make up for the shortfall and more.

The same happened with timber and coal. As Australia’s coal exports fell by $11 billion, the US added $1.8 billion on top of its usual load over the same period. Russia, Canada and Indonesia also sent more.

Markets are unsentimental, when there is a gap they fill them. The US and Australia have made much of their united front on China’s economic coercion, but the truth is American exporters have been eating Australia’s lunch.

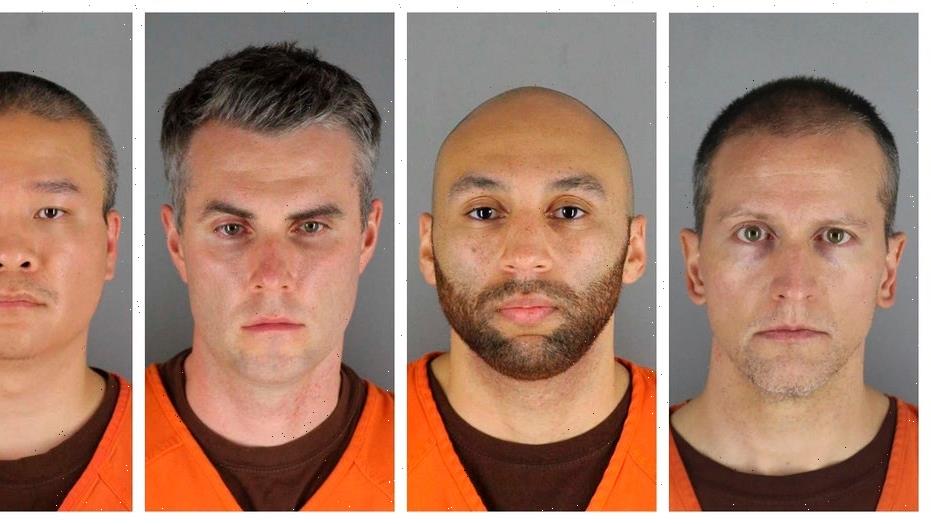

A large screen in Beijing shows talks between Xi Jinping and Joe Biden in November. Credit:Getty

The pain of some producers may be the price to pay for the AUKUS alliance, for Australia’s foreign policy sovereignty, and for regional stability. But as we head into an election year it’s worthwhile being transparent about the costs of doing business.

“Decoupling in any overall sense has hardly begun,” said UTS researchers James Laurenceson and Thomas Pantle, who analysed the Chinese customs data for the Australia-China Relations Institute.

“The scope for costs to rise is ample.”

In the second half of next year, China will re-elect President Xi Jinping for at least a third term and Joe Biden will face the most significant test of his leadership since he took office – the US midterms. Before either takes place, Australia will head to the polls by May.

The timing is important because of the motivations of each of the key actors in election season. The US and China face substantial domestic risks, both economies are slowing, Biden will be focused on domestic infrastructure initiatives, stimulus packages and driving American exports to attempt to smother resurgent Trump support.

Xi has the international spectacle of the Winter Olympics to contend with, fundamental weaknesses in the property and energy sectors, and an internal mission to lock himself in as the most powerful Chinese leader since Mao Zedong.

In this context, the three-hour meeting between Biden and Xi in November was the most substantial between the two superpowers in years. Its goal? To turn the temperature down and allow both leaders to focus more on their domestic priorities.

Australia is now doing its best to turn the temperature back up, despite the ongoing costs to its producers.

Australian elections are always fought on the economy, but they also have another sharper edge: national security. In 2001, it was Tampa and September 11, in 2004, it was Iraq, in 2013 it was terrorism, in 2022 it will be China.

The China campaign has already started. Defence Minister Peter Dutton has wedged Labor on the issue by being provocative, triggering a hyperbolic response from China, and then casting the Opposition as apologists for Beijing’s actions when Labor questions the tenor, not the substance, of his policies.

This is an effective domestic political strategy, but it is a high-stakes, high-risk manoeuvre when the other two major powers involved are pulling in the other direction.

Biden’s Indo-Pacific chief, Kurt Campbell told the Lowy Institute on Wednesday that the US has been very careful about communicating to the Chinese that competition between the two superpowers can be conducted peacefully. “It is essential that we create the mechanisms and the venues where the United States and China can take steps through avoidance, calculation to prevent misunderstanding, to build confidence where necessary,” he said.

In March, Campbell declared that the US would not improve relations with China as long as Australia was being subjected to economic coercion. On Wednesday, he offered praise for Australia’s diplomatic resilience but when pressed on the specifics of whether Biden mentioned China’s trade sanctions on Australia, he said it was part of a range of issues that the US has concerns about, including China’s border disputes with India.

“The President just briefly mentioned activities that China was undertaking that President Biden felt were antithetical to China’s interests,” he said. “So there was a period in our discussion where the President, President Biden, tried carefully to say that some of the steps that China was taking, in his view, were backfiring.”

These are delicate discussions, ranging from nuclear arms dialogues to tensions in the south-China sea, but the broad trend is one of de-escalation. Australia’s plight is at the margins. The White House has been briefing against descriptions of the tensions as a new “Cold War” and for all their bluster China has been reluctant to formally and publicly embrace the reality that they’re engaged in strategic competition with the Americans.

Former Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd is vocal on many issues, domestically his views are tinged with a heavy dose of legacy preservation, but as president of the Asia Society and one of the few Australian politicians who still have back channels into Beijing, his views on China are more sought after internationally than they are at home.

“The bottom line is the official class around Xi Jinping does not want an unexpected adverse development in an election year for him,” Rudd told The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age. “And they can see enough happening in the economy and enough intensity in the security environments relevant to them to be concerned that one of those may become an uncontrollable factor.”

That doesn’t mean Beijing going to zero, that means going from eight out of 10 to a five out of 10 on its relations with the US.

“I think there’s enough coincidence of interests with the US administration and where it has landed for the next 12 months for them to prefer that space as well,” said Rudd. “They are not ready for any one front to get totally out of control in my judgment. And I don’t think at this stage, it is Biden’s interest for the midterms to be on the brink of crisis.”

In this narrow window, there is an opportunity for Australia, but it would involve going against every electoral instinct of the Morrison government. It would not require a concession to Beijing, but it would just require resisting the urge to talk more about China.

“If Australia were being run by realists who viewed the US-China tensions as a national security challenge, rather than an electoral opportunity, we would be using this opportunity in parallel, to take things down a couple of notches,” said Rudd.

There is a precedent. In 2005, Japan condemned China’s actions in the Taiwan Strait, it triggered anti-Japanese protests in Beijing and a diplomatic and economic chill between the two countries. After two years Tokyo dialled down the rhetoric, the heat was taken out of the relationship, careful diplomacy through back channels saw high-level contact resume and, by 2008, Hu Jintao became the first Chinese president to visit Japan in a decade.

History, as it can do in a one-party state, had turned on a dime.

Get a note directly from our foreign correspondents on what’s making headlines around the world. Sign up for the weekly What in the World newsletter here.

Most Viewed in World

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article