How I gatecrashed the Open – twice! A new movie stars Mark Rylance as an English eccentric who bluffed his way into golf’s oldest tournament. Incredibly, our film critic BRIAN VINER did the same… and found himself playing alongside living legends

- Brian Viner followed his hero Maurice Flitcroft and crashed golf’s oldest cup

- Maurice Flitcroft’s story is currently being shown in a new Mark Rylance film

- Flitcroft blagged his way into The Open Championship while he was a beginner

Maurice Flitcroft was an unlikely hero, especially to a 14-year-old boy whose pin-ups were Everton footballers, T. Rex and Suzi Quatro. Flitcroft, by stark contrast, was a 46-year-old shipyard crane driver from Barrow-in-Furness when, in the summer of 1976, he became my inspiration.

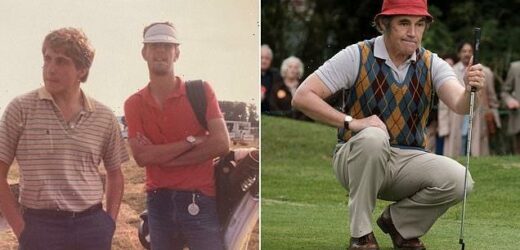

A delightful new film, The Phantom Of The Open, starring Sir Mark Rylance as Flitcroft, tells the story of how — despite having only recently taken up the game — he masqueraded as a professional golfer to play in the final qualifying round for the Open Championship, golf’s most famous and venerable competition.

Flitcroft had become fascinated by golf after discovering it on television just two years earlier. Deciding it looked easy, and convincing himself that he actually stood a chance of winning the Open, he applied to The Royal & Ancient Golf Club of St Andrews (R&A) for an entry form.

The Phantom Of The Open, starring Sir Mark Rylance as Flitcroft, tells the story of how he masqueraded as a professional golfer to play in the final qualifying round for the Open

It asked for his handicap and, as the film tells it, he guilelessly set about writing ‘false teeth, lumbago and a touch of arthritis’ before realising that it meant his golf handicap, a number which is a measure of a golfer’s playing ability — the lower the number, the better you are.

As a beginner, he didn’t yet have one. But handicaps are only for amateur players, not professionals. So Flitcroft’s way round that obstacle was simply to register as a pro.

At Formby Golf Club, not far from Royal Birkdale where the 105th Open was to start a few days later, he duly completed his round in 121 strokes, by some distance the worst score ever recorded in Open qualifying and an embarrassment to the R&A, golf’s ruling body.

Though disabused of the fantasy that he might be able to compete at the highest level, over the ensuing years Flitcroft engaged the authorities in a priceless game of cat and mouse, using ever-more absurd disguises and silly pseudonyms such as Arnold Palmtree — a play on the name of one of the greats of the game, Arnold Palmer — in his attempts to enter the Open again.

In the summer of 1976, when Flitcroft first made his assault on the Open, I lived in Southport, barely a mile from Royal Birkdale, and went to all four days of the tournament.

My father had died suddenly earlier that year, so I was in urgent need of a male role model. But instead of finding one in Johnny Miller, the handsome, blond American who bestrode the fairways like a colossus and won that year’s championship by six shots, I chose Maurice Flitcroft.

The story of his Formby exploits had spread like wildfire. I loved his effrontery and daft bravado.

Eight years later, when the Open arrived at St Andrews, I got my chance to pay belated homage. By then I was a student at St Andrews University, playing golf off a handicap of ten.

That was respectable enough, but still meant I was a lot nearer Maurice’s standard than that of the world’s greatest players. So if I was to pass myself off as a pro at the 1984 Open I needed a smart polo shirt, a pair of what in those days were known as slacks, and a plan.

My best friend, Dominic, agreed to pose as my caddie, and hoisted a (borrowed) bag of clubs over his shoulder. Our aim was to get on to the practice ground, where there was a grandstand full of spectators watching all the top players hitting shots. But there were security guards on the gate. I got past them simply by holding a conversation, within their earshot, with another friend who had obligingly dressed up to look like a pro.

I told him loudly that I’d just come off the course and badly needed to work on my approach shots. With that, the guards smiled us through. We were in.

In the summer of 1976, when Flitcroft first made his assault on the Open, I lived in Southport, barely a mile from Royal Birkdale, and went to all four days of the tournament

Then a third mate, a stooge in the grandstand, called me over to autograph his hat. At that, everyone around him wanted autographs, too. Obviously, they didn’t have a clue who I was. But I was plainly a competitor, by definition part of golf’s elite, so that was enough.

I signed hats, visors, cardboard periscopes, all the paraphernalia you find at golf tournaments, using my own name.

On the driving range there was a spare bay next to Seve Ballesteros, the dashing Spaniard who would go on to win that year’s Open. Had I taken it, and shanked a shot into his ankle, I could have changed the course of golfing history.

Instead, I took up residence on the putting green, reasoning that there was less chance there of being found out by hitting duff shots. For a while there were just three of us working on our game: myself, Greg Norman and Bernhard Langer. Two of the game’s giants . . . and Langer, as I enjoy telling it.

Soon, there was a tap on my shoulder. I thought we’d been rumbled, but it turned out to be an American golf journalist, wanting an interview. I’d scrutinised the list of the more obscure qualifiers in case anyone asked me for my identity, randomly choosing one David Ridley, so that’s the name I gave him. ‘So Dave, no disrespect, but do you honestly think you have a chance of winning the Open?’ he asked.

‘Oh, I will be happy just to make the cut,’ I replied, meaning the competition’s half-way cull.

‘Absolutely f***ing delirious, I should think,’ added my caddie, rather unnecessarily.

The golf writer laughed merrily, not knowing that there was literally no possibility of me even making the first tee, let alone the cut.

I putted for a while longer, then turned my attention to the fleet of chauffeured courtesy cars at the disposal of the players. Again offering my name as David Ridley, I was ticked off a list and given one, which was forced to stop when my pal in the grandstand led another charge of autograph hunters.

Out of the corner of my eye I spotted not Arnold Palmtree but Arnold Palmer, who saw the commotion and looked to see which famous pro was sitting in the passenger seat. I still vividly remember his smile of anticipation turning to bafflement. Who the heck was this guy?

The car dropped us at our favourite pub, the Dunvegan Hotel, where well into the night I drank all the beer that had been promised to me if I pulled off my deception.

It was a story I continued to dine out on, hardly expecting to try it again, but then came the 1999 Open at Carnoustie, some 25 miles north of St Andrews. By then, I was a sportswriter on the Independent newspaper, and was challenged by amused colleagues to see if I could repeat history.

From one of the merchandise tents I borrowed a bag of clubs, persuaded a fellow journalist to be my caddie and, once again, just by looking the part, strode unchallenged on to the practice ground.

This time I was braver, and took a bay between the mighty South African Ernie Els, and the Spanish star Jose Maria Olazabal, who had won the U.S. Masters three months earlier.

Heart thumping, slowing my swing down to reduce the margin for disastrous, tell-tale error, I struck a single ball with a five-wood. By some miracle, it flew straight and true. My caddie, Graham, couldn’t stop laughing. And as we packed up and left, quitting while we were ahead, I heard a man in the crowd say to his wife: ‘It’s incredible how these guys hit the ball, isn’t it?’

He was almost certainly talking about Els or Olazabal but, gloriously, I’ve never known for sure.

A week or so later, after I’d mentioned my previous scam in print, I got a call from the sports desk. A guy called David Ridley, the pro at Coxmoor Golf Club in Nottinghamshire, wanted me to call him. Apprehensively, I did so.

In fact, he couldn’t have been more gracious as I apologised profusely for stealing his identity. But, for him, it had solved a 15-year-old mystery, he said. At the 1984 Open he’d gone to get himself a courtesy car, one of the great perks of qualifying for the Open, only to be firmly told that his name had been crossed off the list and he couldn’t have one.

I still owe him a drink, and, if ever we get round to it, I will insist on toasting the memory of Maurice Flitcroft, a glorious English eccentric, who died in 2007 little knowing that he had helped to fulfil one 14-year-old boy’s dream of ‘playing’ in the Open Championship.

Source: Read Full Article