It started the moment the Albanese government was elected. The government of China started making overtures. Premier Li Keqiang sent the new Australian prime minister a note of congratulations.

It was the first direct communication between the senior leadership of the two countries in 2.5 years: “The Chinese side is ready to work with the Australian side,” he said, to “uphold the principle of mutual respect and mutual benefit”.

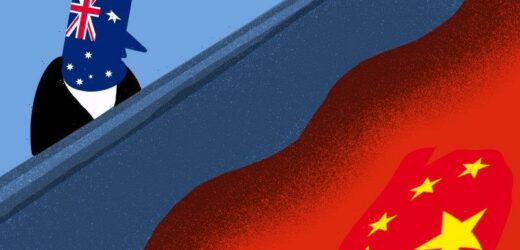

Illustration: Andrew DysonCredit:The Age

Next, Beijing’s ambassador to Australia, Xiao Qian, said that “with this new government in power we are looking forward to a possible opportunity … so that we can put this relationship back on the right track”. The “political relationship” was the source of the problem, he said, and the onus was on the Australian side to make a concession.

On the same day, China’s Foreign Affairs Minister, Wang Yi, said “the crux of the problem lies in the fact that some political forces in Australia insist on treating China as an adversary rather than a partner” and it was time to “seek common ground while shelving differences”.

So, what’s Australia’s move? Australia is under pressure from Beijing on every front. Should Anthony Albanese take the opportunity for a reconciliation? He could claim a diplomatic coup and take the credit.

But no. Three days after winning the election, Albanese made two key points about China relations. The first concerned the list of 14 demands that China’s embassy in Canberra issued to a Channel Nine reporter in November 2020. It begins with a demand that Australia relax its foreign investment rules for China and ends with a demand that Australia’s media stop making critical comments about China. The next day, China’s Foreign Ministry spokesman in Beijing said Australia should “correct its errors”.

“The truth is that Australia is a great democracy,” said Albanese in response to reporters’ questions. “The demands, which were placed by China, are entirely inappropriate. We reject all of them. We will determine our own values. We will determine Australia’s future direction.”

Second was on China’s punitive bans on more than $20 billion worth of Australian exports. “Australia seeks good relations with all countries,” said Albanese. “But it’s not Australia that’s changed: China has. It is China that has placed sanctions on Australia. There is no justification for doing that. And that’s why they should be removed.”

So the agitation for some sort of rapprochement is coming from only one side, China’s. And the new Australian leader has, in effect, declared two preconditions – withdraw the 14 demands and remove the trade bans.

The response from Chinese officialdom? Ambassador Xiao told the Australian Financial Review that Beijing couldn’t drop the trade boycott because “it was not a political decision” but that each boycott on each product was imposed “on the merits of the individual cases”. This is nonsense. The trade bans are pure politics.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Deputy Prime Minister Richard Marles.Credit:James Brickwood

And while he hasn’t been asked publicly about the 14 demands, Xiao has told Australian interlocutors privately that this had been a “gross misunderstanding”. Yet, he will not disown the demands publicly or do anything to clarify this supposed “misunderstanding”.

At the same time, Beijing has been increasing the pressure it applies to Australia. Recall that two Australian writers are being held in detention in China’s system of political “justice”. Blogger Yang Hengjun was detained in 2019 and reports being daily blindfolded and shackled to a chair and interrogated for hours, among other mistreatments.

And broadcaster Cheng Lei was detained in 2020. Last week her partner, Nick Coyle, said she had been allowed no contact with her children or other family. Her only contact with the outside world, a monthly video conversation with Australian consular officials, had now been suspended. Because of COVID-19, supposedly. Apparently, you can catch it over a video link now. Asked about her case, Xiao said it was a legal matter and “should not be a problem” for relations with Australia.

And we now learn China’s air force aggressively buzzed a RAAF surveillance plane on May 26. The Australian plane was on an entirely routine flight in international airspace over the South China Sea.

So while China’s officials present a conciliatory face publicly, they maintain the existing political, economic and military pressures while adding new layers in less visible ways.

Pretending to offer the hand of friendship, they are, in fact, demanding the full kowtow. Offering public platitudes and private pressures, they are seeing whether a new Australian government will crack. It’s a try-on.

This is an astonishingly amateurish misreading of Australia. Why would Albanese make any unilateral concessions? He’s under zero pressure from anyone other than the regime of Xi Jinping. The industries under Beijing’s boycott have mostly adjusted and certainly don’t expect the Albanese government to capitulate.

The Australian people strongly endorse Australian defiance, as polling shows. The new opposition leader, Peter Dutton, on Sunday promised to support the government doing “whatever actions they need to take to keep our country safe”. And countries around the world are looking to Australia as an inspiration in how to withstand the Chinese Communist Party’s coercion.

Last week China’s government threatened New Zealand with trade boycotts. Jacinda Ardern had dared to voice concern over Beijing’s Pacific strategy and China’s human rights violations. Beijing would count it a tremendous victory for Australia to buckle, an example to countries everywhere. It is offering nothing, demanding everything.

The Albanese government has no intention of buckling and no conceivable political gain from doing so. It does intend taking a changed approach, nonetheless.

When he was on the opposition benches, Richard Marles often said the Morrison government took Theodore Roosevelt’s advice – that countries should “speak softly and carry a big stick” – and applied it in reverse. Dutton talked about “preparing for war” but had not equipped Australia with any long-range strike capability to hold an enemy at bay. Everything is on order, nothing is in on hand.

Now that he’s defence minister, Marles is part of a government planning to apply the adage as Roosevelt meant it: To refrain from inflammatory rhetoric while hastening to acquire serious capability. That would be a sincere rejoinder to insincere overtures.

Cut through the noise of federal politics with news, views and expert analysis from Jacqueline Maley. Subscribers can sign up to our weekly Inside Politics newsletter here.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article