Denver: They were young and principled and determined to change the world at a time when it seemed like the world was changing all around them. But even the group of activists and obscure politicians who passed a referendum 50 years ago that blocked Denver from hosting the 1976 Winter Olympics it had been awarded had to think doing so would be impossible.

The year was 1972, two years after the International Olympic Committee had awarded the Games to Denver. Colorado’s most powerful business leaders had been planning the 1976 Olympics for years, hoping to sell a booming Denver to the rest of the world. They had the support of the state’s three-term governor, John Love, the IOC and Richard Nixon’s White House.

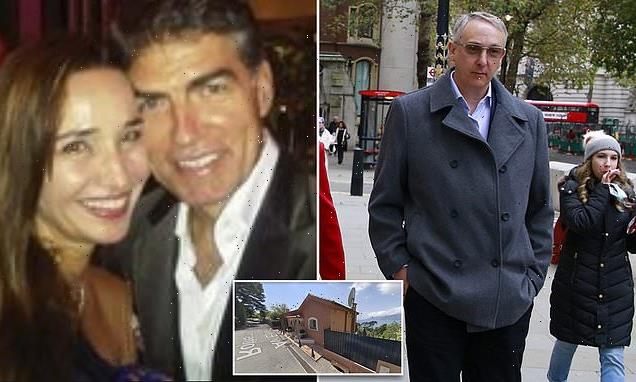

Athletes and officials in the Makomanai indoor skating rink for the closing ceremony of the Sapporo Winter Olympic Games in 1972. The words “Denver, 1976,” can be seen on the electric sign board.Credit:

No city had ever won an Olympics only to give it back. But then it happened, forcing Denver’s planners to decline the Games and the IOC to find another host. The 1976 Winter Games would be held in Innsbruck, Austria instead.

Half a century later, the returned Olympics remain a glowing neon asterisk in Olympic history, “a cautionary tale,” says Heather Dichter, a professor studying Olympic bids at Leicester, England’s De Montfort University about what happens when a city’s organisers fail to grasp the public’s distaste for the financial slough that comes with hosting a Games.

“We meet again in Denver 1976,” reads the sign at the closing ceremony of the 1972 Winter Olympics in Sapporo. The flags of Greece, Japan and the United States fly above the arena.Credit:AP

“Fortunately, we were too young and stupid to think of how audacious it was,” one of the activists, Sam Brown, said in a recent interview.

Led by state representative Richard Lamm, the Citizens for Colorado’s Future successfully portrayed the Denver Games as an unwieldy fiasco that would overwhelm taxpayers, damage the environment and bring more sprawl to an area many in Colorado thought was growing too fast.

They typed brochures, handed out leaflets and visited community halls and Kiwanis Clubs, talking about overpopulation and Olympic budgets filled with hidden costs, always asking the same question: “Who pays and who profits?”

The Denver Organising Committee (DOC) insisted that most of the venues had already been built; in reality, it needed to construct a ski jump, bobsled and luge tracks, a speedskating facility and housing for the media.

Because the IOC insisted that venues be within 50 miles (80 kilometres) of the athletes’ village, Denver couldn’t use ski resorts such as Vail or Steamboat Springs – some three hours away at the time – and instead planned to build a downhill course on nearby Mount Sniktau, an often-snowless peak known for howling winds. Cross-country skiing was to be placed in the Denver suburb of Evergreen.

The DOC suggested trucking in snow before eventually convincing the IOC to let it use the mountain resorts for Alpine ski events.

Opposition to the fanciful plans was small and mostly confined to environmentalists until one day in 1971 when Richard Lamm and his brother Tom, an attorney, gathered in Richard’s office near the Colorado Capitol. There, Richard Lamm, who died last year, spread out a map of the DOC’s proposed sites and laughed.

“It was obvious to Dick right away,” Tom Lamm said. “He was very suspicious of the whole thing right from the start. And the more we began to look at it, there was no way the venues were going to work. The finances were never going to work.”

The DOC was vague about the price tag, insisting the Olympics would cost $US15 million ($21 million) before pushing its estimates to $US35 million. This struck both Lamms as absurdly low.

Alarmed by what he believed would be a financial disaster as well as concerned about accelerating the city’s already rapid sprawl, Richard Lamm recruited Brown and another young activist, Meg Lundstrom, who had been working for the failed presidential campaign of Oklahoma Senator Fred Harris.

Robert Jackson, another state legislator, joined as did a few environmentalists from around Colorado. Another activist, new to Colorado at the time, Tom Nussbaum became part of the group after seeing a television interview with a DOC leader who tried to argue that it was too late for Colorado to vote on an Olympics that had already been awarded.

They printed brochures and newsletters and mailed letters explaining why they thought the Olympics would be bad for Colorado. They also started collecting signatures on a petition to deliver to the IOC that called for the Games to be moved. Within three weeks, their petition had 25,000 names.

“That’s when we knew it had really drawn people in,” Lundstrom says.

The first big move from the Citizens for Colorado’s Future came in January 1972, when three of its members flew to Tokyo for the IOC’s annual meetings before the Winter Games in Sapporo. They burst into the IOC’s executive board meeting and delivered the petition with 25,000 signatures, then told the board that Colorado’s residents wanted to have a say on whether Denver should host the Games.

Support from sympathetic politicians in the US, including Nixon, kept the Denver plan alive, but the DOC’s authority was diminishing as the Citizens for Colorado’s Future gained steam. Needing 51,000 signatures to get a referendum to kill state funding for the Olympics, Citizens for Colorado’s Future got 77,392 in less than five months.

“We were just riding a wave; it’s almost like we could do nothing wrong,” Lundstrom says. “We had so much momentum that all you could do was stay on top of it as it went along and ride it.”

The DOC kept stumbling. It talked about fanciful plans of running trains between Denver and the distant mountain resorts. Rumours flew that the DOC, to guarantee high attendance numbers, was planning a television blackout of the Games in the Denver area.

Denver’s Olympic organisers kept insisting the Games wouldn’t cost more than $US35 million, though later estimates by Olympic supporters went up to $US92 million.

“I think when they put their bid together, they seemed to think they could do whatever they wanted,” Brown said. “To me, they seemed surprised they got the bid and were deer in the headlights. ‘Oh, wow we got it, now what do we do?’ I believe they would have been better prepared if they knew they were going to get it in the first place.”

The show must go on – but it was Innsbruck in 1976, not Denver. Credit:AP

In an apparent attempt to alter its image, the DOC rebranded itself and pushed its establishment status, announcing more business leaders as supporters. Days before the referendum, it ran a full-page ad in the Denver Post, blasting activists as political operatives.

On November 7, 1972 – the same day Nixon was re-elected in a national landslide – Colorado residents voted 537,400 to 358,906 to block additional state funding for the Olympics.

A half-century later, Denver’s abandoned Games remains an outlier in Olympic history, but in Colorado, the referendum was the first of many political earthquakes.

Anti-Olympics campaigner Richard Lamm, pictured here in 2015, went on to become governor or Colorado. Credit:AP

Richard Lamm rode the momentum of the Olympic campaign to be elected governor in 1974, serving three terms. Gary Hart, the young campaign manager for George McGovern’s 1972 presidential campaign, won a US Senate seat that same year. A local lawyer, Pat Schroeder, won the first of 12 elections for House of Representatives on the same day the referendum passed.

“It was the harbinger of what would happen” in future elections, said Steven Katich, a Lamm staffer who was not part of the Citizens for Colorado’s Future.

“The Olympic thing was the first time for us that the establishment order had been upset,” he said.

The Washington Post

Get a note directly from our foreign correspondents on what’s making headlines around the world. Sign up for the weekly What in the World newsletter here.

Most Viewed in World

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article