Our greatest Queen of all: Elizabeth I could crack jokes in Latin and Greek, Victoria came to the throne of a farming nation – and left it in the age of the motor car. Yet still, says historian A.N. WILSON, Elizabeth II was our shining light

During three of the most dramatic periods of change in our national history, we have had a Queen reigning over us — it’s a striking fact.

When Elizabeth I became Queen, the date might have been 1558, but in many respects this country was still medieval.

By the end of her reign, we had the American colonies, Shakespeare had written his plays, and we were recognisably a modern nation.

When Victoria became Queen, ours was a largely agricultural country. During the course of her reign, they built the railways; they designed steamships; the world was linked up by telegraph, and eventually telephone; modern roads were constructed; the motor car era had begun.

In some ways, the changes to Britain during Elizabeth II’s reign were even more momentous. When she was crowned, there was still a British Empire. Half the population went to church.

When Queen Elizabeth II was crowned, there was still a British Empire. Half the population went to church

When Victoria became Queen, ours was a largely agricultural country. During the course of her reign, they built the railways; modern roads were constructed; the motor car era had begun

When Elizabeth I became Queen, in many respects this country was still medieval. By the end of her reign, we had the American colonies and Shakespeare had written his plays

The ‘colour bar’ was endemic in clubs, institutions and professions throughout that Empire — what would later be called institutional racism.

Homosexuality, even between consenting adults in private, was illegal.

Dentistry was scarcely advanced beyond Victorian levels (more than half the adult population over the age of 30 had false teeth).

Murderers and traitors could be, and were, hanged (as were some innocent people merely accused of these crimes).

Most Britons lived in flats or houses with no indoor plumbing. Central heating was a luxury for the rich.

The railways, the steel and coal industries and many other institutions were nationalised. Feminism had barely got off the ground.

Through all these stupendous changes, the head of state has been the same person — Elizabeth II.

And that fact is all the more remarkable when we consider that she was an essentially conservative (small c) woman, both in her personal life and in her attitudes.

At the beginning of her reign, as at the end, her passion was horse racing (though only towards the end did she have a Gold Cup winner at Ascot!).

She liked jigsaw puzzles and essentially solitary activities as a young woman, and as an old woman.

She always seemed like a countrywoman, with none of her sister Princess Margaret’s urban chic, nor her mother Queen Elizabeth’s ease of society manners.

She spent most of her life in London or at Windsor Castle, or doing tours of duty in Britain and across the Commonwealth

She spent most of her life in London or at Windsor Castle, or doing tours of duty in Britain and across the Commonwealth.

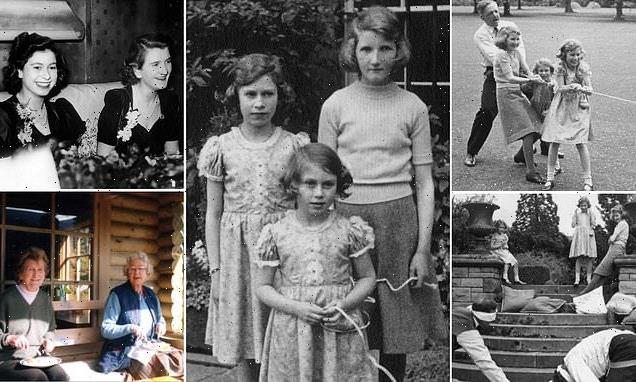

But she always seemed like a countrywoman, with none of her sister Princess Margaret’s urban chic, nor her mother Queen Elizabeth’s ease of society manners.

Placing Elizabeth II beside Elizabeth I and Queen Victoria might, then, at first sight, seem to diminish her.

Elizabeth I was a brilliant linguist who could not only read Latin and Greek but make jokes in either language, and she was fluent in Italian and French. She kept up with all the latest intellectual developments of the day.

She was friends with the spooky but brilliant Dr John Dee, who cast her horoscope, but also told her about the new mathematics and the astronomy of Copernicus. Next to such a figure, Elizabeth II seems like a nicely brought up but countrified duchess — someone who got by in her fluent, bell-like schoolgirl French, but who clearly was not an intellectual, nor someone most at home in the world of the arts or of books. Queen Elizabeth I was, of course, the head of state in far more than just name.

She, with very few advisers, helped to steer the ship of state through the crises of near-war with France, near-invasion by Spain, wars in the Low Countries, quarrels with the Pope and so on.

Queen Elizabeth II was once asked what she thought of the republican cause and gently (though, of course, with an impish irony) replied: ‘Well, I’d go quietly.’

She would have done, too, if the republican movement had been highly developed during her reign.

Princess Elizabeth was formally proclaimed Queen on February 8, 1952. She was crowned in Westminster Abbey (pictured) on June 2, 1953 – by coincidence the same day a joyous nation learned a Commonwealth team had conquered Mount Everest

When her Golden Jubilee came up, it was scornfully predicted that there would be no great enthusiasm. In fact, hundreds of thousands of British people lined the streets

Through the worst periods, such as the time just after the death of Princess Diana, it was openly suggested that the monarchy had had its chips.

Wiseacres would appear on television to say that, in their great generosity, they would allow the Queen to go on until she died, but that after this, it would be time to have an elected President.

When her Golden Jubilee came up, it was scornfully predicted that there would be no great enthusiasm.

In fact, hundreds of thousands of British people lined the streets. Just tourists, said the liberal intelligentsia and the Hampstead dinner-party crowds. Not so.

In the ten years after that, the popularity of the Queen and her husband, Prince Philip, soared, and with it, the idea of the monarchy.

By the time of the Diamond Jubilee, the adoring crowds numbered millions.

It’s quite an achievement for a small, unassuming woman who, in her voice, manner and upbringing, seemed so utterly at variance with what we would have guessed to have been the spirit of our times in more recent decades.

After all, we now live in an extrovert era, replete with misery memoirs and letting it all hang out — notably so in the case of her grandson Harry.

She was someone whose inner thoughts were probably a little bit of a mystery even to her nearest and dearest.

Elizabeth’s father King George VI, her mother Queen Elizabeth and sister Princess Margaret at London Airport to wave her off ahead of the tour. He died six days later.

When everything else changed, she stayed, if not the same, at least recognisable, and increasingly timeless

We are secular. She was deeply pious. We are embarrassed by the class system. Her voice, although modified by speech therapists over the years, was always from the era of Celia Johnson and Trevor Howard in Brief Encounter.

Was that, in fact, the secret of Queen Elizabeth II’s huge success as a monarch? That she was a character from a black-and-white movie who survived in the era of 3D and Techni- color? Partly.

She doggedly held on to all that was sacred to her in the past, including the role of Queen itself when some had urged her to abdicate — and this was undoubtedly an ingredient in the success story.

When everything else changed, she stayed, if not the same, at least recognisable, and increasingly timeless.

But that is not the only reason for her enduring legacy, and her great success as a monarch.

Compare her with Queen Victoria for a moment.

Victoria started out (following a brief honeymoon period) as rather unpopular. Then she became even less popular, with more than 50 republican movements being founded in the decade after her husband Prince Albert’s death in 1861.

And then her popularity began to pick up, as the new voters — the working-class voters who liked the British Empire — saw her (rightly) as the embodiment of all they stood for.

By the standards of a modern royal, Victoria broke all the rules

By the standards of a modern royal, Victoria broke all the rules.

Intensely shy, she needed cajoling even to perform quite simple rituals, such as opening Parliament, and she scarcely went out in public to open bridges or factories or to visit hospitals.

This seclusion did not endear her to the public. Ever afterwards, conscious of the fact that Victoria helped make Middle England anti-monarchist, the Royal Family has been out and about.

‘I have to be seen to be believed,’ is one of Queen Elizabeth II’s best-known sayings about her job.

She certainly was seen, and she certainly was believed.

It is hard to think of any public servant, head of state, Pope or diplomat who worked so hard, or for so long, just at being seen.

The world tours were constant, until she became too frail. The tours of Britain, likewise.

There cannot have been an area of Britain which she did not visit, and as her life went on, the public began to see that this ‘meeting the people’ was more than just a ritual exercise.

Few people who were alive at the time will ever forget her visit to Ireland in May 2011, when she bowed her head in silence beside a war memorial.

It was a gesture which was typical of her style. The memorial commemorated those Irish who (controversially in republican Ireland) had volunteered to fight for Britain during World War I.

To that extent, it was a highly conservative gesture. At the same time, her bowed head was a token of sadness and regret for all the slaughter, all the bungling, all the misunderstanding between Britain and Ireland over the years.

Deeply Christian woman that she was, where there was injury, she brought pardon; where there was hatred, she brought love.

This was confirmed when — to everyone’s delight — she began her speech at the grand state banquet with a few words of Irish.

The state visit to Ireland was only the most dramatic of thousands of trips which this remarkable woman made during her long reign.

The state visit to Ireland was only the most dramatic of thousands of trips which this remarkable woman made during her long reign

Although she was considered cold and unfeeling by many, she actually worked a sort of magic with her personal charm.

One of the most cynical men I have ever known, the journalist Alastair Forbes, once said to me: ‘When you are with her, you know yourself in the presence of Absolute Goodness.’

That can, of course, be rather disconcerting, and it certainly did not mean that she was soppy. On the contrary.

In 2013 there was a grand lunch given by all the men who had served as her pages. One of them, David Ogilvy, was given the terrifying role of playing the piano and singing to her.

(She had sent to him a list of her favourite songs, such as You’re The Cream In My Coffee and, from Oklahoma!, People Will Say We’re In Love.

When David’s father met the Queen a few days later, he said: ‘I gather my son’s been entertaining you.’

‘Trying to,’ was the monarch’s rather terrifying reply. But the personal touch was all her way of sustaining this apparently obsolete institution, monarchy.

It had a profound effect on the development of the Commonwealth.

Almost the only major political clash of her reign — between the head of state and the Prime Minister — was that with Margaret Thatcher over the issue of sanctions imposed on apartheid South Africa.

Unlike Mrs Thatcher, the Commonwealth overwhelmingly backed economic sanctions on the regime — and on that issue the Queen was proved right.

The peaceful toppling of the de Klerk regime and of apartheid was in no small measure because of her.

Queen Elizabeth II, like all sensible and successful small-c conservatives, saw that you could not halt change in the world. She hardly ever tried to do so

Diehard conservatives might have been surprised by the ease with which, for example, she accepted the abolition of the hereditary principle in the House of Lords, or the changes in the Church of which she was Supreme Governor.

In the first case, she was a pragmatist. She saw that it was inevitable that the hereditary peers would have their powers curtailed, if not altogether removed, and she was not going to tie the monarchy — a popular institution — to the unpopular hereditary peers.

Diehard conservatives wanted to say: ‘If you believe in an hereditary monarchy, you must have an hereditary peerage.’

She would have seen where this argument led — abolish the Lords, and you have also abolished the monarchy. She was too canny for that.

And the success of her great Jubilees taught her that the monarchy had a mysterious bond with the people which was dependent upon neither the hereditary principle alone, nor religion alone — important as that was to her.

In the matter of female priests, she was progressive. Princess Margaret once told me: ‘As God’s representative in this realm, my sister would like women priests and women bishops.’

No part of this sentence was a joke.

Queen Elizabeth II, like all sensible and successful small-c conservatives, saw that you could not halt change in the world. She hardly ever tried to do so.

In small matters — such as having a website and putting the Royal Archives online — she was up to date.

She accepted that society had changed in all manner of ways in the long years of her reign.

But while she adapted in matters which were adaptable, she did not change when it came to any of the principles which she believed to be eternal.

Her sense of public duty was unwavering. Her belief that she was God’s servant, placed by providence to defend the monarchy, was serious and strong.

In girlhood she had seen the near- extinction of the monarchy in Britain when her Uncle David abdicated as Edward VIII.

The Europe in which she grew up had thrown off its kings and tsars and embraced fascist and Communist dictators.

She knew what the alternatives to constitutional monarchy were, and she knew that she had a duty to maintain it.

As we grieve for our Queen, we should remember that the survival of the monarchy over the past century was not an inevitability.

It happened largely because of one woman’s unselfish devotion to duty, but also her supreme confidence that it was an institution worth preserving.

Source: Read Full Article