A fortuitous break in lockdowns allowed me an interstate visit to the town of my birth – the place where my parents had grown up and established our family.

I visited many familiar settings where I had spent my early years, and was reminded afresh of the link between memory and place.

Seeing places which had endured through my absence, and those which had been replaced, reminded me of people long gone who now lived in my memory.

I recalled the relationship my mother had with the butcher, the bread, milk and grocery trucks we would ride from my grandparents’ home around to our own as they undertook their daily deliveries. I saw the renewed tennis courts where my parents had met, the church which generations of my family had as their spiritual home.

There was a comfort in visiting those places, reminding me of family roots, but also a yearning to ask questions which I never thought to ask my parents and grandparents while they were alive. Things which were never written down but which would have been formative experiences for them, and ultimately for me.

The experience also reminded me of the importance of oral history. So much is never written down but shapes ensuing generations nonetheless. Ancient cultures maintained a strong connection to oral history – the stories passed from generation to generation to remind communities and their members of their origins, their values, and their connection to the land of their ancestors.

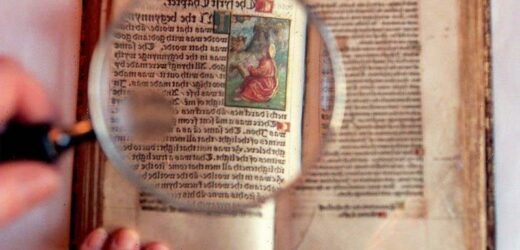

The only complete extant copy of the 1526 edition of William Tyndale’s translation of the New Testament, the first ever printed in English from original sources.Credit:AP

It is worth noting that much of the Bible owes its existence to oral history; stories that were told and retold, passed through generations with great care to ensure that the people of God understood their history, identity and purpose. That they survive today in written form is due in no small part to storytellers being removed from the land which birthed them in the first place.

Much of the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) owes its existence to the exile of the Israelites into Babylon. Disconnected from the land which held and prompted their memory, it was committed to text form. The New Testament similarly owes its written existence to disconnection from place. The Gospels were written after the Christians were exiled from Jerusalem – the land which Jesus walked – from AD66, while the letters of Paul to the churches are written in his absence from them. And who, reading these narratives which were crafted to ensure that the memory could be transferred from generation to generation in oral form, does not yearn to sit with those who shared these stories orally and ask deeper questions which the text itself does not answer?

The journey of faith and identity requires an inquisitiveness to explore, to ask deeper questions and to ponder what more there is to this story which is our family, our lives and our hopes. While we hold written words to be of high value, there is a deeper truth to be told, if only we are prepared to ask, to listen and to ponder, for in such stories we might hear the voice of God.

Gary Heard is a Baptist minister and Woodbridge Adjunct Professor of Pastoral Theology at Trinity College Theological School in the University of Divinity.

Most Viewed in National

Source: Read Full Article