When Arthur Calwell was immigration minister in the 1940s, he would tell a story he heard from his mother about his grandfather, Michael McLoughlin.

He said that McLoughlin was an Irishman who “jumped ship” to settle in Victoria in 1847.

Convict descendant Garry McLoughlin with a photo of his second cousin, former federal Labor leader Arthur Calwell.Credit:Penny Stephens

Calwell, who later became federal opposition leader, admitted he had found no records to prove this.

In fact, McLoughlin was a convict. Michael’s great-grandson Garry McLoughlin discovered that in 1843, Michael was sentenced to 10 years in Van Diemen’s Land – which changed its name to Tasmania in 1856 – for stealing a gun in rural Ireland.

If Calwell, from Melbourne, never knew this, he wasn’t alone. In her new book Vandemonians: The repressed history of colonial Victoria, University of Melbourne emeritus professor Janet McCalman estimates 30,000 Tasmanian ex-convicts came to Victoria. One of them was bushranger Ned Kelly’s Irish father, John “Red” Kelly, transported in 1841 for stealing two pigs.

The book tells how they covered up their pasts to avoid shame and discrimination. “Vandemonian” was a slur used across Victoria against anyone suspected of being an “old lag” or “from the other side”.

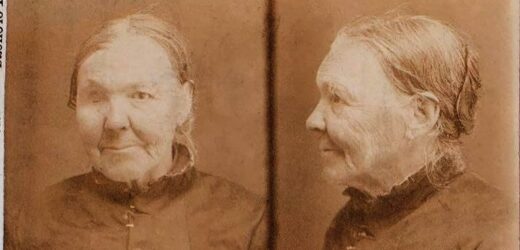

Former Tasmanian convict Ellen Miles pictured after her arrest for vagrancy in Melbourne 1896. Credit:Public Record Office Victoria.

It was feared they would contaminate respectable society. Professor McCalman said ex-convicts would have been “terrified” of being exposed, so they omitted from records, or didn’t tell children, they had even been to Tasmania.

She found that many convicts were “doomed” by early trauma.

Ellen Miles, a destitute former brothel keeper, was charged with vagrancy in Little Lonsdale Street in 1896.

In 1839, she had been convicted in London of passing a counterfeit coin. She was 11 years old, had been in custody 30 times and her mother was dead. Ellen’s father wanted her transported so he wouldn’t have to support her.

James Blackburn, transported to Van Diemen’s Land for forgery, went on to design a water supply for Melbourne.

Professor McCalman said most convicts didn’t reoffend and blended into society. Irishwoman Mary Fennelly, transported for theft in Liverpool in 1840, married a pastoralist and later skins dealer Jesse Fairchild in Melbourne in 1849 and on her 1907 death left a huge estate worth £37,000 including a St Kilda terrace house.

Her obituary said she had travelled to Europe 14 times.

The book cover. Credit:Melbourne University Publishing

James Blackburn, a civil engineer, architect and surveyor, was transported in 1833 for cheque forgery in London.

In Van Diemen’s Land he designed buildings and a bridge, moved to Melbourne in 1849 and designed the city’s water supply.

The book, based on six years of research involving 60 volunteers, traces passengers from 126 convict ships and their descendants.

Garry McLoughlin, 80, of Armadale, was a researcher on the project. Like Arthur Calwell, he hadn’t found Michael McLoughlin in shipping records until Professor McCalman suggested he try convict records.

Garry said he and other relatives were surprised and sceptical at having a convict in the family.

But Michael’s personal details and signatures of Michael’s, both as a farmer in Kyneton, Victoria, and in Irish court documents, matched. “I’m quite certain about it now,” Garry says.

But he says Michael could have been innocent – the witness to the firearm theft was a 14-year-old boy and the local clergy, gentry and the crime victim supported Michael’s court appeals.

The Morning Edition newsletter is our guide to the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article