When the lights snapped out at the drag show in Moore County, North Carolina, the producers and performers thought: This was unlikely to be a coincidence.

As of Dec. 8, authorities were still investigating the attack on two substations, which took out power for about 45,000 people for four days. They haven’t found any evidence it was tied to the show.

However, there was reason to suspect it was. The show had drawn hatred and threats, with online comments threatening lynching and castration. People called and verbally berated the teenagers who worked at a shop that sponsored the show, Sandhills Pride executive director Lauren Mathers said at a Dec. 8 press conference.

“It hit hard. It hit fast. It was loud. It was scary,” she said.

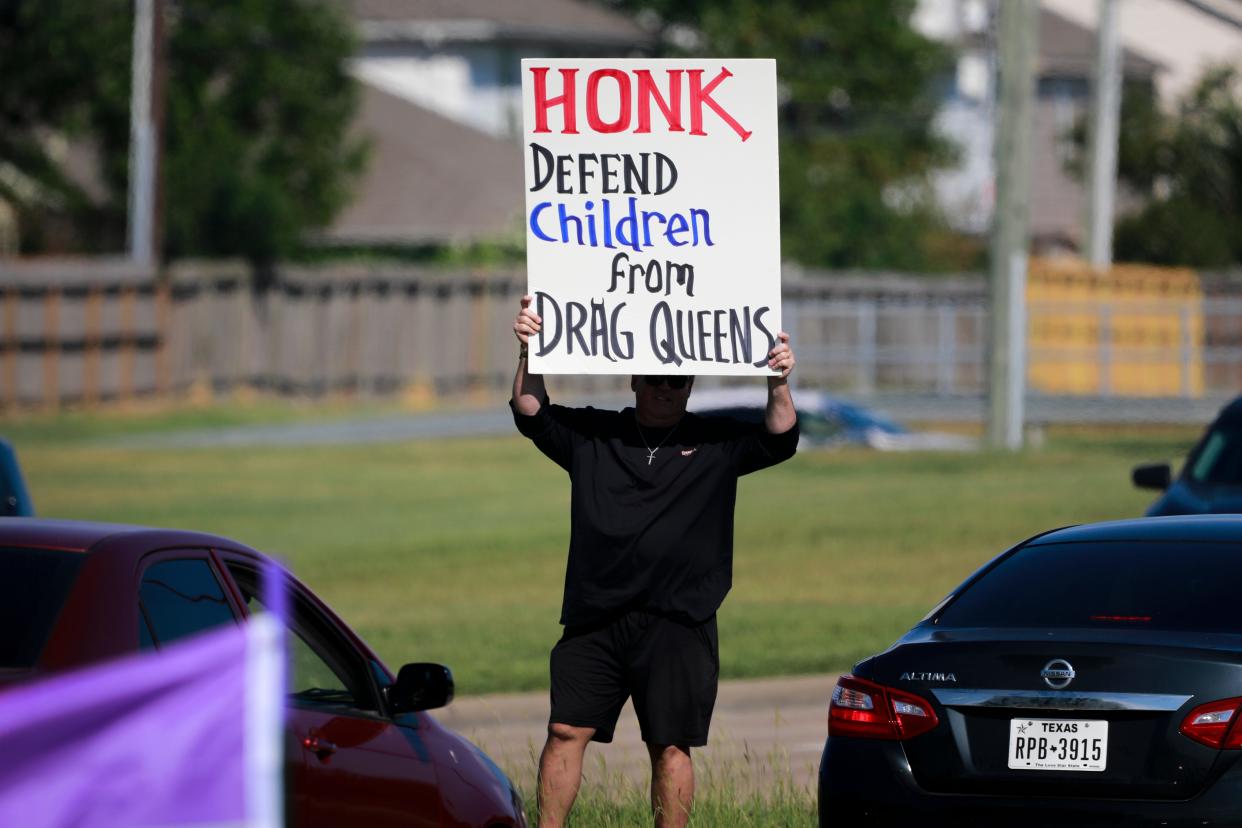

Especially scary because it was one of an increasing number of drag shows, across the South and the nation, facing threats and protests — at least 126 in 2022 through mid-November, including 48 in the South, GLAAD reported. The highest number of threats were in North Carolina, followed by Texas. Legislative efforts to limit drag are underway in six states and the U.S. House.

The backlash comes after LGBTQ rights, visibility, prevalence and acceptance have blossomed.

On Dec. 8, Congress passed a bill guaranteeing recognition of same-sex marriages — with bipartisan support. Over 70% of Americans support same-sex marriage, including a majority of Republicans, according to Gallup. The share of Americans who identify as LGBTQ doubled to 7% over a decade, according to Gallup — including 21% of Gen Z. Five percent of young adults told Pew they are trans or nonbinary.

Drag performers typically wear elaborate costumes that exaggerate traditional gender norms, and perform stylized routines — often lip-syncing to popular songs, telling jokes or singing. They may show cleavage, not unlike Dolly Parton. It’s most common to wear women’s clothing, but performers may be of any gender and wear pretty much anything — there are drag kings as well as queens, and performers who blur gender entirely. If you’ve seen the musical “Hairspray” or any of 40-plus Bugs Bunny cartoons, you’ve seen drag.

In other words, drag is mainstream. Shows remain a gathering place for people who feel marginalized in the straight world. They are also popular with bachelorette parties. “RuPaul’s Drag Race” has international editions. A reality show that brings drag shows to small towns is in its third season.

Despite the progress, the threats are terrifying. The Proud Boys came, armed, to a show in Memphis, Tennessee. Earlier this month, someone shot at a Washington State brewery that plans a Drag Queen Story Hour. Alabama drag queen Victoria Jewelle has hosted shows wondering the whole time if “me and my girls are going to have to run out the side door,” she said.

What’s going on?

The history of drag in the South

Drag performance is old — in LGBTQ spaces and far beyond.

In the 1800s, U.S. Navy sailors dressed as women or mermaids for ceremonies to honor King Neptune, the U.S.S. Constitution Museum writes. (Today, Navy yeoman Joshua Kelley performs as Harpy Daniels with the catchphrase, “Serving Country, Serving Looks.”)

Troupes on the Black “chitlin’ circuit” often featured a drag performer. A Black paper enthused in 1901 about “female impersonator” Augustus Stevens, who “is making nightly hits in his single turn. He will soon stage one of Papinta’s famous serpentine dances.” Four decades later, Little Richard would begin his career as Princess Lavonne.

Up to 100 years ago, Southern churches, both Black and white, held womanless weddings and pageants as fundraisers, historian John Howard said. They’d play on gender roles by making “the most pompous macho man the bride, the shortest, thinnest man the groom,” Howard said.

Drag blew up in queer spaces after World War II. Gay New Orleans Mardi Gras krewes held drag balls throughout the 1960s, according to 64 Parishes. In the 1970s, “Drag” magazine chronicled balls, shows and pageants across the country. At the 1972 Miss Gay America drag pageant, for instance, Miss South Carolina won Miss Photogenic and Miss Tennessee won the swimsuit contest.

Poet Minnie Bruce Pratt went to her first drag show in Charlotte, North Carolina, in 1981 with fellow National Organization for Women state delegates. She remembers “fabulously beautiful people in pink spangled evening clothes lip-syncing to great music, us singing along,” she said.

In Tuscaloosa, Alabama, in the ‘80s, Michael’s Club was the place to go for drag fans from counties around, Howard said. Magnolia emceed wearing a giant wig and quoting the old standby, “the higher the hair, the closer to God,” while her parents worked the door. She’d bring the house down duetting with her mother to the Judds song “Mama He’s Crazy,” her mother on acoustic guitar.

Why now?

Staff at the ACLU and the Family Research Council both said they haven’t found an organized campaign to limit drag shows.

Rather, social media and conservative news outlets have buzzed over a handful of videos of drag performances with children in the audience.

Outcry over these events spurred Tennessee Senate Majority Leader Jack Johnson to file a bill that’s been characterized as banning drag. Johnson said that’s inaccurate.

The bill would limit all sexually explicit performances in areas where kids could be present, he said: “It doesn’t matter if it’s by someone who’s dressed in drag or not.” It would not affect drag shows in age-restricted venues, or people in drag marching in a parade or reading at a G-rated story hour, he said.

He did not want to promote violence or vitriol, he said.

“There’s no place for hatred. Hatred leads to violence sometimes,” he said. “We can have public policy agreements and disagreements and we need to work those out through the proper channels in our various legislative capacities, but I don’t want to be associated with any sort of hate or violence.”

Johnson said he had not gone to a drag show, though he mused, “I’ve gone to Vegas.”

Larger context

People like Johnson say they just want to make sure children aren’t exposed to sexual material, like parents of all stripes don’t want kids seeing online porn.

That said, attacks on drag are part of a larger firestorm opposing children’s exposure to LGBTQ people and content. Opposition started pre-pandemic with Drag Queen Story Hours and similar daytime events that moved drag out of queer clubs. There have been efforts to remove books from school libraries and limit discussion of gender and sexual orientation in the classroom. Johnson has also pre-filed a bill banning gender-affirming care for minors.

“We seem to be in the middle of an anti-LGBTQ, an anti-trans and an anti-drag panic,” Minnie Pratt said. “It’s a pushback against social change.”

Some of the opposition stems from the belief that queer and trans behavior goes against God’s will.

“With the children, we’ve got a crisis. The building is on fire,” said Sharayah Colter, a member of the Conservative Baptist Network’s steering council. But underneath that, “It’s not right to be questioning the identity that God has given people when he has created them — he creates them male and female.”

From that perspective, it doesn’t matter if a drag queen is wearing an evening gown reading “Goodnight Moon”: It’s gender-bending, and it’s unacceptable.

Colter and some evangelicals believe the prevalence of LGBTQ people in the cultural discourse, including through drag, makes people, especially children, more likely to be gay or trans.

“I don’t think that God is creating people to be LGBTQ,” she said.

Familiar talking points

Accusations that gay people are trying to groom or convert children are familiar. They are also untrue. There is zero evidence that LGBTQ people are more likely to molest children. Science has found sexual orientation and gender identity are innate, “influenced by genetic factors,” GLAAD spokeswoman Barbara Simon said.

At age 5, long before Victoria Jewelle had any exposure to a gay or trans person, “I knew something was different with me,” she said. When her mother left the house, Jewelle would put on her red shoes and feel right. She was groomed to be straight, she said. It didn’t work.

As for the raciness of drag performances, queens said they know how to tailor shows to audiences. Just like Bob Saget could be family-friendly on “Full House” and X-rated in a nightclub. Besides, there’s state law, Jewelle said: “You have to keep everything covered. Even if it’s fake, it has to be covered!”

Drag is about art and transformation, “the art of illusion,” Jewelle said. As she walked down a staircase at a wedding gig to Beyonce, shimmering with rhinestones, a 4-year-old boy stood agog. “She’s so pretty!” he gasped.

“The only thing that child took from that experience was that he had the opportunity to see something that was very beautiful. I don’t see the sexualization in that,” Jewelle said.

Also old: LGBTQ criminalization and resistance.

Police routinely raided those New Orleans balls. A 1972 issue of “Drag” magazine reported that four men were arrested at Memphis’ The Door lounge. The performers were booked on charges they impersonated females, and the owner for permitting men to sing, dance and kiss in dresses and wigs. “Crime is certainly rampant in Memphis!” the magazine noted, with a practically audible eye-roll.

“We were felons,” Pratt said. In the 1970s, she lost custody of her two sons because she was a lesbian. The Supreme Court didn’t overturn sodomy laws until 2003.

Threats to drag shows, “It’s intimidation. We can’t give into it,” Pratt said. “We’ve pushed back in the past, we’ve won in the past and we’ll win this time around.”

“The show still goes on, even though you petrified,” Jewelle said, laughing.

And maybe the best way to win is to win them over.

They’ve got friends in low places

Last November, Jewelle put on the first drag show in Prattville, Alabama.

“We were getting threats that they were going to drag us across the bridge, and they was going to show us that Prattville didn’t accept drag and all that stuff, and we was immoral,” she said.

The show was at Carl’s Country, a straight bar featuring honky-tonk music in a cinderblock building with a Confederate flag on the wall. Jewelle is Black.

The audience was mainly straight, conservative and white — men in ball caps, Wranglers and boots — there perhaps out of curiosity. Jewelle laid out the rules: no touching the performers or dancing on them or getting in their space.

As the crowd stood awkwardly, she added, “I don’t know if anybody told you, but I am a man.” Everyone burst out laughing.

And then they all had a great time.

“They was really supportive!” Jewelle said.

At the end of the night, the owner asked where the performers wanted to take a photo. Jewelle said, “Right in front of this rebel flag!”

Now, Carl’s Country books drag shows regularly.

“They call us their queens,” Jewelle said.

Danielle Dreilinger is an American South storytelling reporter and the author of the book “The Secret History of Home Economics.” You can reach her at [email protected] or 919-236-3141.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Drag shows have a long history, even in US South. Why the threats now?

Source: Read Full Article