By Patrick Hatch and Nick Toscano

On June 8, 2000, Australia got a glimpse of a possible future for its automotive industry.

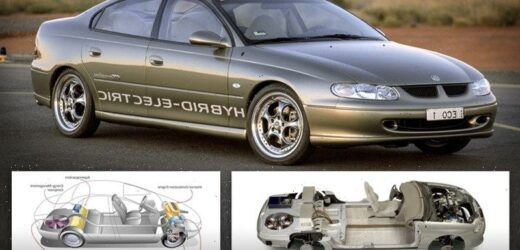

It looked familiar enough – like a sleek remake of the best-selling Holden Commodore – as it drove towards Uluru, trailing the Olympic Torch Relay.

But inside the iconic frame was something new to these shores: a hybrid powertrain, combining a four-cylinder engine with a 50kW electric motor.

The ECOmmodore hybrid concept Holden and the CSIRO developed promised to use half the fuel as a conventional model but was never put into production.

Holden and the CSIRO, which developed the electric motor, its super-capacitors and lead-acid batteries, said their ECOmmodore concept vehicle used half the petrol of a conventional model and produced dramatically lower emissions.

“It was clearly the way of the future – it was what we had to do,” says Laurie Sparke, who was Holden’s head of innovation at the time and led the carmaker’s two-year collaboration with the CSIRO.

“Environmental issues were already of great concern – fuel economy, emissions, global warming – even at that stage.”

The world’s first mass-produced hybrid car, the Toyota Prius, was months away from going on sale in Europe and the US after it launched in its native Japan three years earlier.

Sparke says he had one meeting with the Holden board to convince them to keep investing in the hybrid concept, arguing the technology was vital for the company’s future success.

“Their response was: ‘our customers want V8s, they don’t want electric cars’,” he says.

Holden’s decision makers may have been right at the time. Now the world has changed, and quickly.

Six years after Holden, Ford and Toyota shut their last local assembly plants, the electric car revolution is now firmly upon us. Advocates predict enormous opportunities for Australia – from mining critical ores to producing battery chemicals.

Some even believe the age of EVs could go so far as reviving a local automotive manufacturing industry.

“It’s a once-in-a-century opportunity,” says Shannon O’Rourke, head of Australia’s Future Batteries Industries Cooperative Research Centre. “The world hasn’t seen, and will never see, another opportunity quite like it.”

Australia has some of the world’s biggest known reserves of so-called “critical minerals” – the metals that go into EVs and the batteries that power them.

It is already the world’s top producer of lithium, and among the biggest producers of nickel, cobalt, manganese ore and rare earths.

The International Energy Agency estimates demand for EV batteries will grow more than tenfold this decade, stretching production capacity and supply of the materials that go into them.

Robyn Denholm, the Australian-born chair of Elon Musk’s Tesla, the world’s biggest EV maker, says the company is on track to spend more than $1 billion a year on lithium, nickel and other metals mined in Australia.

Rather than just digging up minerals and watching others get rich with them, she says Australia should drive the dawn of a new industry further up the value chain.

The Albanese government has its eyes on the same prize. Last year it opened consultations on Australia’s first electric vehicle strategy, with one stated aim to developing policies to encourage “manufacturing of EVs, chargers and components”.

On the sidelines of a US energy conference in Pittsburgh in September, Energy Minister Chris Bowen was unequivocal: “We can make electric vehicles in Australia – not only do I think that, so do the EV manufacturers.”

The allure of a new industry that creates thousands of high-skilled jobs, drives the transition to zero-emissions technology and diversifies the economy away from raw material exports is hard to resist. But making that a reality is another thing.

O’Rourke believes Australia is in “pole position” to capture the opportunities in manufacturing and become a green energy superpower – and he uses that term deliberately.

“It is a race that everyone wants to win,” he says. “We’re seeing very aggressive moves by our friends and rivals to capture the industry. Unless we act decisively, Australia risks being left at the starting line.”

Australia is already well behind when it comes to the uptake of EVs. They made up just 3.4 per cent of new cars sold last year, compared to 10 per cent globally, 19 per cent in China and 86 per cent in Norway.

And the handful of homegrown electric vehicle startups say they have fought an uphill battle to survive.

“Tortured is one way of putting it,” says Tony Fairweather of his 10-year journey as founder and CEO of SEA-Electric.

SEA installs a proprietary electric drive system into light commercial vehicles out of its factory in Dandenong, and this week announced a deal worth almost $1 billion to supply 8500 electrified Toyota Hilux and Land Cruiser utes to the Australian mining industry.

Garry Clerkes and Dzung Huynh, at SEA-Electric’s plant in Dandenong, where the company installs electric engines in utes and other commercial vehicles. Credit:Simon Schluter

The company was on the verge of collapse in 2020 when, Fairweather says, one of Australia’s big four banks called in a $4.5 million trade finance facility loan, giving him six months to pay it back.

“That bank came to me… and said ‘we don’t believe in electrification, we need you to pay down your working capital line’,” he says. “That was the only funding we had and they took it away.”

Fairweather blames the then-Coalition government for devastating confidence in the industry. Prime minister Scott Morrison had accusing Labor of trying to “end the weekend” with its policies to increase EV sales, and Small Business Minister Michaelia Cash promised tradies the government would “save their utes” from the opposition.

“You can’t raise funds in a market when everybody around you at all levels are pretending electric vehicles don’t exist and aren’t part of the future,” Fairweather says.

Facing oblivion, Fairweather relocated to the United States and found a drastically different environment, raising $US75 million ($108 million) from investors to keep SEA alive in Australia and funding a US expansion.

“It’s extremely disappointed that it couldn’t be funded and supported from within its own country,” he says. “There’s been a real shift in the belief in electrification, but that’s only happened in the last six months.”

Mining for motors

While local EV companies may have struggled, booming EV sales elsewhere are quickly becoming an important economic driver for Australia. Exports of the minerals they use like copper, nickel and lithium were worth $22 billion last year and forecast by government to hit $33 billion this year.

The international focus on Australia as the new frontier for EV minerals has been building for some time, says Madeleine King, the federal resources minister. “But now it’s like it’s on hyper-speed,” she says. “Everyone wants a piece of what we’ve got.”

Almost all of it is shipped thousands of kilometres for processing and turned into higher-value products like battery cells in China and other Asian countries.

Australia has 50 per cent of the world market for raw materials needed to make batteries, the Grattan Institute think tank calculated last year, but less than 1 per cent of the market for the next stage of the value chain.

King says the Albanese government is eager for the country to move beyond mining towards the more complex businesses such as refining ores into battery-ready chemicals for batteries’ anodes and cathodes – widely considered to be the most lucrative end of the value chain.

Tesla CEO Elon Musk speaks during the official opening of the new Tesla electric car manufacturing plant near Gruenheide, Germany, last year. About 70 per cent of the lithium for Tesla’s batteries comes from Australia and its chair says the country has untapped potential to develop an EV industry. Credit:Getty Images

“Right now, we’ve got to start with the basics, and it’s about exploration and setting up the mines,” she says. “But then, increasingly, investment in refineries that are proximate to the source of critical minerals and rare earths is increasingly a focus … and once we get that part of it right, then we can move further downstream, building cathodes and anodes – even batteries.”

King agrees that it’s possible for Australia to kick-start manufacturing of batteries or EVs if we can attract international investment. “But I think we need to make sure we do all of the other slightly more boring parts too,” she says. “Talking about refining or processing is not as exciting as building a car, but it’s absolutely essential.”

China dominates the EV battery value chain. It’s where almost all (97 per cent) of Australia’s lithium is processed and it makes three-quarters of the world’s battery cells.

An Australian EV battery – with minerals dug up, refined, processed, turned into cells and loaded into a battery pack – is a long-term ambition for Brian Craighead, founder and CEO of Energy Renaissance.

Brian Criaghead, CEO of Energy Renaissance, says local production mandates would help get the industry off the ground. Credit:Steven Siewert

He says the company already makes lithium battery packs with 92 per cent local components and intends to become the first group making battery cells in Australia later this year, from a new “gigafactory” set to open in Tomago, just north of Newcastle.

“There’s nowhere enough battery capacity to meet just electric vehicle demand, so demand is going to outstrip supply for a long time to come and therein lies the opportunity,” he says.

Energy Renaissance expects its biggest market will be stationary industrial storage and commercial vehicles, like trucks, delivery vans and buses. Craighead hopes they will be a catalyst for more industry development, creating demand for local mineral processing and supply for EV builders.

Despite these ambitions, Craighead and Fairweather both believe a wider EV industry won’t emerge without the same government support and intervention which has spurred a rush of battery making investment in the United States.

The Biden administration’s blockbuster Inflation Reduction Act, passed in September, offers consumers tax credits of up to $7500 for buying new EVs, but only if a large percentage of its battery is made in North America (starting at 50 per cent this year, rising steadily to 100 per cent in 2029).

An electric vehicle charges at a public fast-charging station in London. The UK and EU will ban petrol cars in 2035. Credit:AP

Craighead argues Australia would be foolish not to have similar mandates as its energy transition gets underway. He points to the NSW government’s plan to electrify its fleet of 8000 buses.

“If the NSW government were to say, we want these to be mostly Australian made — at least 70 per cent — that would in a stroke of a pen create 3 gigawatt hours of demand,” he says. “We would have to open two more factories and hire another 15000 people, and that’s just one example.”

Likewise, Fairweather says a Biden administration mandate forcing 55 per cent of automakers’ truck and ute sales and 75 per cent of commercial van sales to be electric by 2035 was driving SEA’s success there.

“That is a policy that could easily be implemented into Australia at no cost and would drive the uptake of urban delivery vehicles very quickly,” he says.

Christiaan Jordaan, CEO of Sicona, a battery technology start-up based in Sydney, said protectionist trade policies, led by the US, are “winning…and if we sit on the fence we’ll lose out”.

Sicona has developed a composite silicon-graphite-carbon material to use in battery anodes which it says can increase an EV’s charging capacity by 50 per cent, and hopes to start commercial scale production in 2025.

And while Jordaan said the Albanese government had a better understanding of the opportunities the EV industry presented for the country than the coalition, it was becoming harder to resist moving his start-up to the US, as battery makers and investors there express interest in his company’s technology.

“I don’t want to move — I want to actually see something happening in my own backyard,” he says. “Understanding has improved. But ambition, I’m yet to see”.

Some progress on the home front is being made. In November, a joint venture between Australian miner IGO and China’s Tianqi began production of lithium hydroxide — a refined lithium product suitable for battery cells — at its new Kwinana refinery in WA. Other companies including Wesfarmers, Mineral Resources, Liontown and US giant Albemarle are involved in nearby projects to begin producing lithium hyroxide from as early as next year.

Meanwhile, Perth-based miner Lynas is building a $500 million facility just south of the WA outback gold-mining town Kalgoorlie to process rare earths from its Mt Weld mine, a four-hour truck drive away.

Lynas is the only major non-Chinese producer of separated rare earths – a group of metals needed to make magnets for smartphones, military weapons, wind turbines and EVs – and the facility will be the first in Australia to carry out value-added processing.

“We have an ambitious plan to grow with the market including investing over $1 billion in new facilities in Australia,” says Amanda Lacaze, the company’s chief executive.

Lessening their reliance on China for rare earths is a major concern for Western governments. European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen said last year that those materials would soon be more important than oil and gas and that the bloc “must avoid becoming dependent again, as we did with oil and gas”.

Lacaze says Australia is in an excellent position to supply the critical minerals the world needs for the energy transition given its skilled workforce, environmental credentials and safety standards.

But to attract further downstream investment and build Australia’s reputation as a globally competitive manufacturing destination, significant investment will be needed in “21st-century infrastructure” such as renewable power stations and cost-effective logistics, she adds.

Proximity to the raw materials may be advantageous, but the high cost of paying workers, taxes and manufacturing in Australia compared to competitor countries looms as a possible hurdle to the nation’s ambitions to seize a bigger slice of the EV supply chain.

As automakers ratchet up efforts to preserve the “green” image of EVs, they are increasingly having to scrutinise supplies to ensure their materials are sourced as sustainably as possible. According to King, this could be where Australia may have an edge on other countries, and could attract a “green premium”.

Sparke finished his 43-year career at Holden in 2007 and set up his own EV start-up, EDay Life, which folded 10 years later after it was unable to attract enough investor support.

He hopes the country will finally grasp that EVs are a chance to restore some of the high-skilled jobs and advanced manufacturing know-how that was lost when the local auto industry shut down.

“I think it’s essential for Australia and the welfare of the community to get this growing,” he says. “Australia was able to be at the leading edge of a lot of stuff, and it all got blown away.”

The Morning Edition newsletter is our guide to the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in National

Source: Read Full Article