‘I thought we’d been hit by napalm because of the horrors we witnessed’, says Falklands War hero Simon Weston on his 60th birthday as he calls himself the ‘luckiest guy alive’

- Simon Weston CBE, 60, was horrifically burned when serving in Falklands War

- He was the most injured serviceman to survive when his ship was hit by bombs

- In total, 48 men died aboard his vessel, Sir Galahad, many of them burnt alive

- Over the next four years he underwent over 90 operations, mainly skin grafts

- But Simon says he is the ‘luckiest guy alive’ and is ‘hugely fortunate’ to be here

A carefree boy from the Welsh valleys, he lived for his next game of rugby and a few pints in the pub with his mates. By his own admission, at the age of 20 he had a selfish streak.

For the next four decades he was a very different person, first fighting to survive, then struggling to rebuild his life after being horrifically burned serving in the Falklands War.

He would eventually become a selfless charity leader, a global inspiration – and Simon Weston CBE.

Next year sees the 40th anniversary of the 1982 South Atlantic war that almost stopped Simon reaching his 21st birthday. He turns 60 today.

Simon, a Welsh Guardsman, was the most seriously injured serviceman to survive when his ship, Royal Fleet Auxiliary vessel Sir Galahad, was hit by three Argentine bombs.

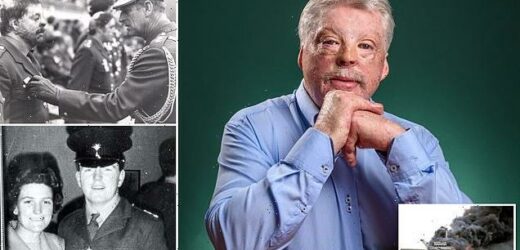

Simon Weston (pictured), 60, a Welsh Guardsman, was the most seriously injured serviceman to survive the Falklands War when his ship, Sir Galahad, was hit by three Argentine bombs

In total, 48 men died aboard Sir Galahad, including more than 30 of his comrades from the Welsh Guards, many of them burnt alive.

When Simon returned to Britain with 46 per cent burns, his mother didn’t recognise him. He had lost an ear and his eyelids and suffered dreadful damage to the rest of his head, to both hands and much of his body.

Amid the trauma, his weight would eventually drop from 16 stone to just eight. Over the next four years he underwent more than 90 operations, mainly skin grafts.

Yet sitting on a stool in the kitchen of his Cardiff home, Simon Weston is quite serious when he tells me of his good fortune.

‘I am the luckiest guy alive and I am hugely fortunate that I am here,’ he says. ‘My heart stopped twice, they gave me the last rites and at one point it looked as though I had been blinded, but I regained my sight.

‘I still do the lottery, but I think I used up all my luck back in 1982. There were 48 men on my ship who would have wanted my luck.’

Today, Simon is at peace with his former demons. A family man who works out in the gym three times a week, he no longer suffers nightmares. With his wife of 31 years, Lucy, he has three grown-up children and two grandchildren. He is content.

‘I am no longer defined simply by the terrible injuries that I received but instead by what I have achieved since,’ he says with a justifiable hint of pride.

Simon Weston was born on August 8, 1961, in Caerphilly Miners’ Hospital, close to his grandparents’ home in Nelson, Mid Glamorgan. He was his parents’ second child, and his mother, Pauline, considered him the ugliest baby she had ever seen.

Simon’s father, David, worked as an operating theatre technician for the RAF. At the time, the family home was at RAF Wegberg in the Rhineland, but Mrs Weston had wanted her son to be born in her native Wales.

Next year sees the 40th anniversary of the 1982 South Atlantic war that almost stopped Simon reaching his 21st birthday. Pictured: Simon getting South Atlantic Medal from Prince Philip

As he grew up and his parents separated, Simon was close to his maternal grandmother and spent a lot of time at her house in Nelson.

As a teenager he had the occasional brush with the law, and was cautioned for riding in a car stolen by older friends.

In 1978, aged 16, he was recruited into the Welsh Guards. Simon initially found military discipline challenging but soon thrived and played prop forward for the Army Under 21 rugby team. He served in Berlin, Northern Ireland and Kenya.

Then, on April 2, 1982, the Falkland Islands were invaded by Argentina, and the Welsh Guards were assigned to the Task Force sailing 8,000 miles to the South Atlantic.

Simon left Southampton aboard the newly requisitioned QE2 on May 12, waved off on the luxury liner by his mother, stepfather and grandfather.

‘It was surreal,’ he says. ‘It felt like we were in a movie from the Second World War. We all thought the fighting would be over before we got there. There was even a banner which read, ‘Thank you, Maggie, for my cruise.’ ‘

On May 28, Simon and his fellow Welsh Guards ‘cross-decked’ to the cruise liner Canberra, which had been converted to a troopship. By then the conflict was at its height and the mood utterly changed.

Once they had entered the Total Exclusion Zone (TEZ), they knew they were targets. ‘This was for real and the fun was over,’ he says.

The next day they arrived off the Falkland Islands and were sent to San Carlos Water, where they waited instructions on supporting the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of The Parachute Regiment.

On the morning of June 8, 1982, the Welsh Guards were moved from San Carlos Water to Bluff Cove aboard the unarmed landing ship Sir Galahad – without a protection vessel.

Simon takes up the story at the point when most of his platoon were below deck towards the stern of the ship.

He says: ‘It was a beautiful day, bright and sunny. But we had been kept on the ship for far too long. The back door had been opened and there were guys sunbathing. Then we got our order to load our gear on to the pallets to be winched out.

‘Then, about mid-afternoon, still a beautiful day, we heard the alarm, ‘Air raid warning red. It’s green, it’s green, get down, get down.’ I got into a crouched position. There was a shuddering rip of metal as 500 lb of bomb came crashing through just where my best friend was sleeping.

‘The [ship’s] fuel ignited and then the bomb detonated. I was the closest man to the bomb to survive. I genuinely thought we had been hit by napalm, because of the horrors that I saw. I tried to help a friend of mine but he died in my arms. I also asked for my gun [to shoot himself if necessary] because I didn’t want to be burnt alive.

‘Then I just felt a small waft of air and I ran through the thick, black smoke and orange flames.

‘On the tank deck there were bodies everywhere, some dead, some still alive but with horrific injuries. I got helped to the top of the ship and sat there waiting for the helicopters to take us off.’

While still on the ship, as he waited for a Sea King helicopter to lift him to safety, he had all his clothes cut off other than his T-shirt and underpants.

‘I was given some morphine and someone wrote a big M on my favourite T-shirt,’ he says – to show he’d been given the painkiller.

Horribly burned, Weston asked a fellow soldier for an assessment of his ‘wedding tackle’, recalling that ‘he was reluctant to look but then he did and announced, ‘You are all fine.’

He adds: ‘My thought had been, if all that was charred and gone, there wasn’t a lot of reason to come back home.’

Weston was flown to an emergency triage centre at Ajax Bay.

In total, 48 men died aboard Sir Galahad (pictured), including more than 30 of his comrades from the Welsh Guards, many of them burnt alive

‘The next time I woke up, I was blind,’ he continues. ‘My eyes were so swollen that all I could see was grey shadows moving around and then nothing at all. I was so thirsty I would have exchanged my family for a single can of Pepsi. But then I passed out again.’

The next three weeks were spent on the hospital ship SS Uganda, where the surgeons carried out an operation to save Simon’s sight.

Yet his first telegram from the ship to his mother read: ‘Safe and well on hospital ship Uganda. Just a superficial burn but improving very fast. Coming home soon. Playing rugby straight away. Please show to Susan [his then fiancee]. Love, Simon.’

Weston explains: ‘I didn’t want my mother to worry until I was home. She couldn’t do anything to help me so I thought it was the best thing to say. Of course, I was very, very poorly.

‘I was incredibly fortunate to have the best medical treatment possible – then and for the next few years. I can never thank the doctors and nurses enough for what they have done for me. In fact, they saved so many of us who didn’t have the right to live.’

It was only when Simon eventually arrived back in the UK, going first by ship to Montevideo, Uruguay, and then by plane via Ascension Island, that he learnt that 48 men had died on his ship and 94 more were badly injured.

His aircraft landed at RAF Brize Norton, Oxfordshire, and an ambulance took him to the medical centre at RAF Lyneham in Wiltshire, where his mother and grandmother were waiting.

‘Look at that poor boy,’ Weston heard his mother say, before he cried out: ‘Mam, it’s me. I am OK. At least I’m alive.’

Simon adds: ‘When she finally realised it was me, her face turned to stone and her legs went from under her. It was hard for her. By that point, I had looked in a mirror, and that was quite distressing as I didn’t recognise myself.’

His next treatment came at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Woolwich, South-East London, where a plastic surgeon outlined the likelihood of years of operations.

‘It was difficult to take some of the news that came my way because I was exhausted and demoralised. The consultant spelt out the truth about how difficult the future was going to be,’ says Simon.

He was briefly allowed out of hospital on August 7, 1982, to celebrate his 21st birthday the next day at home with his family.

There were many low points over the next few years. His fiancee Sue left him not long after his return from the Falklands.

He became dependent on painkillers, he started drinking too much and, at one point, he attempted to kill himself with a crossbow.

Unsurprisingly, he was suffering from depression and what is now recognised as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Simon also suffered from survivor guilt.

‘I had a total lack of self-worth,’ he reflects. ‘My fiancee had gone, along with my career, my sport and much more. I didn’t know how I would fit in, what I could do with the rest of my life. I had no vision of the future.’

In 1985 he was discharged from the Army with a lump-sum payment of just £9,000 and modest service and war pensions.

But the BBC documentary Simon’s War and other programmes about his life had already brought public recognition, and soon he was on a new path.

‘I made a conscious decision to help others – to try to make a difference,’ he says.

Simon set up his own national youth charity, Weston Spirit, which he co-ran for the next 20 years. Today he supports numerous organisations, including the Falklands Veterans Foundation and DEBRA, the charity for ‘people whose skin doesn’t work’.

He was made an OBE in 1992 and then CBE in 2016. Simon was delighted, as a staunch royalist, to receive both honours from the Queen. He met his wife, Lucy, while running his charity.

When Simon returned to Britain with 46 per cent burns, his mother (both pictured) didn’t recognise him. He had lost an ear and his eyelids and suffered dreadful damage to his body

Since being injured he has also learnt to fly, started motor racing and freefall parachuted from the wings of a plane, despite a fear of heights.

A key moment came a decade after the war when he asked to meet the Argentine pilot, Carlos Cachon, who had bombed Sir Galahad.

‘I had suffered from the same terrible nightmare for years: this black jet would scream overhead with this hooded figure with flaming red demonic eyes. Carlos was told all of this and he said straight away, ‘Yes, I will meet him. I helped create his problems, now I want to help solve them.’

‘We eventually met in an apartment in Buenos Aires and we got on well. We had been enemies in conflict but we didn’t have to be enemies in peacetime.’

A second meeting with Cachon and five return visits to the Falklands have also helped Simon’s recovery.

Nearly 40 years on, Simon believes Britain was correct to go to war for the rights of 1,820 islanders, even though the ten-week conflict cost the lives of 255 British military personnel, 649 Argentine military personnel and three Falkland islanders, with a total of 2,432 men wounded in battle.

‘Baroness Thatcher was incredible,’ Simon tells me. ‘She made the right decision and she didn’t take it lightly. I have always felt comfortable with my injuries because I know we did the right thing.

‘There are different types of courage, and moral courage is sometimes the hardest to find.’

Tonight, Simon will celebrate his landmark birthday with a family dinner. He now earns his living as a motivational speaker and running a facilities management company, but unpaid charity work still takes up much of his time.

He adds: ‘I am excited by life and what the future holds. I am still hungry for success.’

As he enters his seventh decade, he acknowledges there have been ‘two Simon Westons’ so far.

‘The first Simon was a bull in a china shop who could be compassionate but also selfish,’ he explains.

‘But my experiences after 1982 have shown me a different way to live – to be more considerate of others. In many ways, my charity work has been my saviour too, as it has given me a reason to get up in the mornings.

‘I liked the person I was but I like the person I am a bit more.’

Lord Ashcroft KCMG PC is an international businessman, philanthropist, author and pollster. For information on his work, visit lordashcroft.com.

Follow him on Twitter and Facebook @LordAshcroft. Falklands War Heroes, his seventh book on bravery, will be published by Biteback in November.

Source: Read Full Article