Four years after Joanna Toole and six other Brits died on Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302, her father celebrates a landmark victory that proves it was no random accident

From early childhood, Joanna Toole liked to keep rats in the bedroom of her home in Exmouth, Devon. She said they were extremely intelligent and made good pets.

Other animals she kept included hamsters, a rabbit, two giant African land snails and pigeons, which she trained to fly home.

At secondary school, she discovered some boys throwing stones at a bird’s nest in a hedge. She confronted them, and the boys made up an unkind ditty about her, which spread throughout the school.

For years afterwards, pupils would taunt her with the song. But her position was clear: to protect animals from needless suffering, even if it meant exposing herself to harm.

When she grew up, Joanna became a consultant to the UN Food and Agriculture Unit. Her passion was ocean conservation — in particular the harm done to wildlife by discarded fishing nets. In March 2019, 36-year-old Joanna was invited to speak on the subject at the UN environment assembly in Nairobi, Kenya.

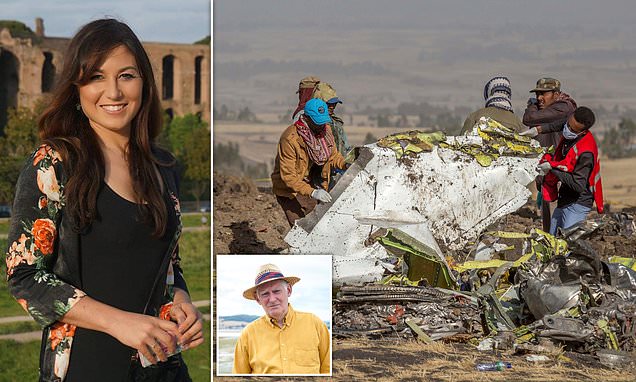

Joanna Toole (pictured) was 36 when she – along with eight other Britons – died after a 737 with a flawed new control system crashed

The night before she left, she had dinner with her partner, Paul, at their home in Rome. He worked at the Irish Embassy, and they’d met at a conference four years earlier. They were planning to move back to the UK, get married and have children.

Joanna had a brief stopover in the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa, before continuing her journey on Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302. There were 149 passengers, from 35 countries, and eight crew members on board.

The plane, a Boeing 737 MAX 8, took off at 8.38am local time on March 10. A minute and a half later, the nose of the plane pitched downwards. A faulty sensor had registered incorrectly that the aircraft was at too steep an angle and was about to stall. This had triggered new software which had automatically pushed the nose down.

‘What’s going on?’ said the captain, Yared Getachew, at 8.39am, according to the cockpit voice recorder. The pilots struggled to regain control of the plane, but the software kicked in and drove the nose aggressively down.

The pilots tried again. ‘Pull with me,’ urged the captain to his first officer, Ahmednur Mohammed. But the automated system overrode them. The recording stopped 23 seconds after the pilots’ fourth attempt.

Six minutes after take-off, Flight 302 nose-dived at 175mph, crashing into farmland, near the village of Ejere, 32 miles from Addis Ababa, killing everyone on board.

Early that morning, Joanna’s father, Adrian, was at home in Devon when he heard about the crash from the BBC News website.

Rescuers work at the scene of an Ethiopian Airlines flight that killed Joanna in March 2019

There had been five planes flying that morning from Addis to Nairobi, and it took until lunchtime before Paul could confirm Joanna had indeed been on the doomed flight.

‘It was like the end of the world,’ says Adrian, 71. He exhales deeply. ‘All that promise cut short. It just seems so very unfair — it should have been me rather than her.’

For the past four years, Adrian, Paul and the other bereaved families have dedicated themselves to proving that the crash wasn’t a random accident.

It was an avoidable tragedy: Boeing had prioritised profit over safety, concealed critical safety issues and put the flying public at risk.

‘As the story has unfolded, it’s been revelation after revelation,’ Paul says. ‘My beautiful daughter died in a death trap. Why hasn’t Boeing faced justice?’

READ MORE: Families of Britons who died in plane crash in Ethiopia accuse Boeing of playing ‘Russian roulette’ with people’s lives as inquest into tragedy opens

At an inquest held in Horsham, West Sussex, earlier this month, a coroner delivered a verdict of unlawful killing into the deaths of Joanna and humanitarian workers Sam Pegram and Oliver Vick. Finally, the families had their landmark moment — they had taken on Boeing and won.

For years, Boeing had evaded and spun, with scores of lawyers, advisers and PR fixers. But now the families had an official ruling that a crime which had led to the deaths of their loved ones had been committed.

‘Boeing is a behemoth. To go up against them and get a result like this is a David and Goliath feeling,’ says Vincent Nichol, the solicitor representing the nine British victims.

After so many setbacks, Adrian is still processing the news. ‘I’m relieved’, he says, when we meet in his home in Exmouth. ‘In that verdict, I found some consolation.’

As well as being chair of the Joanna Toole Foundation, set up to continue her work protecting animals, Adrian volunteers for Sailability, which introduces young people with special educational needs to sailing. But his loss clearly runs deep.

‘People say that when your child dies, a part of you dies as well, and that is certainly the case,’ he says.

Joanna was born in 1983, but Adrian separated from her mother, Patricia, a year later. They remained close, however, and ‘a period of negotiation’ resulted in the birth of Joanna’s sister, Vicky, in 1987, although the girls’ parents still chose to live separately. ‘It was a fairly unique arrangement,’ he says.

Patricia remarried and had a third daughter, Karen. But the family remained unified and when Patricia died of cancer in 2016, they were all with her.

Joanna’s father Adrian Toole (pictured) is now fighting for justice for his daughter, whose life ended in tragedy

A surveyor by training, who worked in the North Sea oil industry, Adrian has become, by force of tragic circumstance, an expert in aeronautical engineering, too.

When Boeing developed the 737 MAX, in 2011, it was rushing to compete with the Airbus A320 neo, he tells me. That aircraft was innovative, fuel-efficient and favoured by budget airlines. Rather than designing a new plane, which would have been costly and time-consuming, Boeing refreshed their 737, which dates back to the 1960s.

Boeing made the engines larger to increase fuel efficiency, and positioned them slightly forward and higher up on the plane’s wings. However, the relocated engines caused the plane’s nose to pitch skywards.

To compensate, Boeing added a computerised system known as MCAS (Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System) to prevent the nose from getting too high and causing a stall.

Boeing’s key selling point was that pilots could fly the planes without expensive retraining because they were essentially the same as previous generations of the aircraft.

Yet, by the time Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 took off on March 10, 2019, red flags had already been raised about the new control system.

In 2016, the chief technical pilot for the 737 MAX told a colleague in a text that MCAS was ‘running rampant’ and ‘egregious’, meaning very bad, in a simulator.

If a pilot took more than ten seconds to react to mistaken MCAS activation, the result could be ‘catastrophic’, according to a Boeing document in 2018.

However, these concerns weren’t disclosed to the Federal Aviation Administration, which enforces regulations covering manufacturing, operating and maintaining aircraft.

Ms Toole died onboard a passenger flight from Ethiopia to Kenya in March 2019

Consequently, the MCAS wasn’t mentioned in flight deck manuals or pilot training material.

It was ‘unconscionable’ that Boeing, the FAA and the airlines ‘would have pilots flying an aircraft without adequate training, or even providing available resources . . . to understand the highly complex systems that differentiate this aircraft from prior models’, according to a pilot who filed an incident report with Nasa’s Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS), where reports can be submitted anonymously.

Adrian remembers watching the news in October 2018 after a Lion Air 737 MAX crashed into the Java sea, 12 minutes after taking off from Jakarta, Indonesia, killing all 189 people on board.

Of course, it was a tragedy, but he didn’t think anything of it.

By then, he was six years retired from the oil industry and a committed environmentalist.

‘Jo knew I didn’t approve of her flying, but we both knew she would carry on. Her career consisted of going from place to place, from conference to conference.’

Five months later, Joanna’s plane crashed in similar circumstances. At first, Adrian felt no suspicion. The revelations would come later.

Joanna’s body was finally repatriated in November 2019, eight months after the crash. The family had sent her hair brush to the police to help with DNA identification from the crash debris.

‘I said to the rest of the family: ‘We are not going to inquire about what exactly is in that coffin.’ They told us it was Joanna’s body and that’s how we treated it.’

They scattered Joanna’s ashes ‘into the waves’ at her favourite beach in Cornwall.

It had been just a few weeks after her death that the family’s battle for justice began.

Wreckage is piled at the crash scene of Ethiopian Airlines flight ET302 in 2019

‘I asked Jo’s uncle if he could look into legal remedies, and he started setting up meetings with solicitors in London. I can recall walking down High Holborn to see one set of lawyers and I was crying. At that time, I was saying to myself: ‘I’m doing my best for you, Jo.’ ‘ It was the first time Adrian had allowed himself to cry. Under normal circumstances, he wouldn’t have considered therapy — ‘I am a fan — but not for myself.’ But the hospice where his mother had died, six weeks after Joanna, offered him sessions with a bereavement counsellor to talk about his mother’s death.

‘And, of course, it wasn’t long before Jo’s death came up as well. And that lady allowed me to talk about Jo and my mother.’ The inquest was cathartic, too, he says. It felt like a ceremonial shaming. Boeing had brought destruction to the families, and representatives from those families had gathered to tell Boeing’s legal representatives about their loss and their pain.

‘I clapped when the coroner left,’ says Adrian.

The verdict was a ‘public statement of the wickedness of Boeing’, says Sean Gates, CEO of Gates Aviation Ltd, which provides legal and safety consultancy to the aviation industry.

But it is largely symbolic. ‘Pushing a criminal prosecution in the UK against Boeing or individuals based in the U.S. would be very difficult,’ he says.

However, today the inquest verdict is to be submitted as evidence to a Federal Appeals Court hearing in New Orleans.

The families seek to overturn a ‘deferred prosecution agreement’ that Boeing struck with the U.S. Justice Department in 2021 — a ‘sweetheart deal’ that guarantees Boeing and its top executives immunity from federal criminal prosecution over issues surrounding the aircraft’s software.

The settlement ordered Boeing to pay $500 million (£389 million) to the families of the victims of the Lion Air and Ethiopia airlines crashes, and $2.5 billion (£1.96 billion) in fines and fees, but rules out any other charges.

Technically, the families should have been consulted, under the Crime Victims’ Rights Act. But the deal was struck secretly, so they were shut out of discussions.

‘We didn’t know about it until our lawyers read about it in the papers,’ says Adrian.

What keeps him going is his fight for justice — he wants Boeing’s former chief executive, Dennis Muilenburg, and other executives prosecuted — and a promise to keep Joanna and her mission alive.

There is a photograph of her on the sitting room wall of his home, which was taken a few months before she died. Staring straight at the camera, her eyes are steady, there’s a hint of a smile.

Every day, Adrian stands in front of the photo and speaks to his daughter. ‘Very often, what I’m saying to her, is: ‘I’m doing my best for you, Jo,’ ‘ he says.

Source: Read Full Article