By Tim Elliott

Avi Yemini, the Melbourne-based, right-wing-provocateur-cum-journalist, is often described by his detractors as full of hate. Which may be true. He does appear to have a pronounced dislike of trans-rights activists, climate science, Waleed Aly and almost everything to do with the ABC. But if you really want to know who Yemini is, it’s perhaps more useful to look at what he loves. He loves working out, which he does religiously, every morning, between 8am and 9.30am. He loves the state of Israel and the Israel Defence Forces, which he served in for three years. He loves making fun of climate change and COVID-19 restrictions. He really loves former US president Donald Trump. He also loves sad Ashkenazi religious pop music, which reminds him of his Orthodox Jewish upbringing and which can, in his more vulnerable moments, reduce him to tears.

But most of all, Yemini loves attention. At school, he was the class clown. Growing up, he was the family comedian. Between the ages of eight and 10, Yemini regularly pretended to faint. Doctors would come and say, “We don’t know what’s wrong with him.” His parents became desperate. They sent him to hospital, which Yemini enjoyed because he got to watch Postman Pat on TV. But then the doctors gave him a CAT scan. Thinking he was going to get caught, Yemini held his breath until he almost passed out.

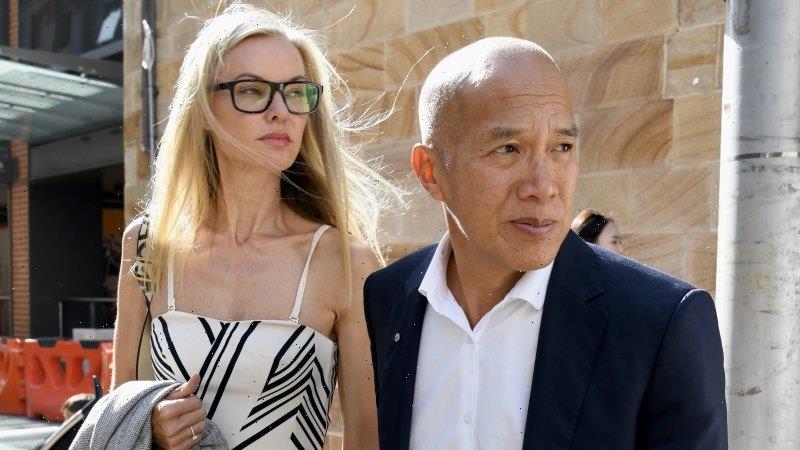

Avi Yemini at the Eureka Freedom Rally in Melbourne in 2021. “Avi’s an agitator, a provocateur,” says his brother, Manny Waks. “But I’m yet to be convinced that he believes a lot of what he does.”Credit:AAP

“One of my brothers knew I was faking, and I hated him for it,” Yemini tells me when I meet him for lunch at Laffa Bar, a kosher restaurant in Melbourne. “He leaned over to me one time, and goes, ‘Just stop it. You’re worrying everyone.’ And I thought, ‘You piece of shit – you know!’ ” (Only years later did Yemini tell his father he was faking, “and I still don’t think he believed me”.)

Yemini is short and compact, with a thick beard, dancing eyebrows and a head of springy black hair which he wears pulled back into a bun, high on his head, like a pompom. He is 37 years old, but seems possessed by the spirit of a 15-year-old boy, propelled by manic impatience from one moment to the next, as if on some critical mission, which, as far as he and his audience goes, he is.

In 2020, Yemini became the Australian correspondent for the Canadian far-right online media outlet, Rebel News, where he’s built a substantial following by “telling the other side of the story Down Under”, delivering his hyper-partisan reporting and commentary to a cumulative audience of 4 million across Twitter, YouTube, TikTok, Instagram and other social media platforms. A born performer and compulsive opportunist, he’s emerged as one of the most virulent – and controversial – critics not only of Victorian Premier Dan Andrews, but of what he considers to be the entire middle-class, soft-left orthodoxy, an unspoken consensus he believes exists between “woke elites”, an entitled political class and a compliant mainstream media.

Yemini has plenty of critics. Some regard him as a misinformation super-spreader and indeed, a danger to democracy; others, like his older brother Manny, suspect he doesn’t even believe much of what he says.

As a self-proclaimed outsider, Yemini’s career depends on conflict, and he’s forever locked in a sado-masochistic death-grip with his detractors, who label him an Islamophobe, a neo-Nazi and a wife-basher. (In 2016 he threw a chopping board that hit his ex-wife, for which in 2019 he pleaded guilty of assault. He also pleaded guilty to harassing his ex-wife with abusive text messages for over a year. She told the court that Yemini had terrorised her during their volatile relationship of 10 years, treating her like “a vessel for his hatred” instead of a human being.) But like many culture warriors, Yemini has a thick skin, not to mention an excellent radar for moral panics.

On this day in August, he’s covering a protest on the steps at Victoria’s Parliament House by a group called Binary, and has invited me along. Binary, which is fronted by Christian values campaigner Kirralie Smith, is fighting to protect young children from “radical gender theory” and “LGBTI indoctrination”. About eight or nine people have shown up, some holding placards that read, “LET KIDS BE KIDS!” and “IF YOU CAN’T DEFINE A WOMAN, YOU CAN’T PROTECT WOMEN”. As Yemini and his cameraman confer on how best to film them, I get talking to Smith.

“We are here letting people know that the government promotes children being transitioned without parental knowledge,” she says. “It’s a socialist Marxist thing.” (A spokesman for the then Minister of Equality, Harriet Shing, later tells me the government recognises there are situations in which students, though under 18, may be sufficiently mature to make their own decisions.) According to Smith, gender transitioning presents all kinds of perils, including the breakdown of the family unit, and men competing in women’s sport, with the attendant risk of men using female change rooms. “Why should penises be allowed in women’s change rooms?” she asks.

Yemini concedes much of what he does is “putting out a persona”.Credit:Josh Robenstone

Moments later, Yemini films a piece to camera with Smith and her supporters, most of whom appear quite elderly. He teases them about being “young” and “hot”, before asking if they would trust Dan Andrews to mind their children. “Not on my life,” one woman replies.

By this time, people are recognising him. “Onya Avi!” yells a passing motorist. A schoolboy stops to congratulate Yemini on his TikTok videos. I’m busy taking notes when I’m suddenly face to face with a woman in wraparound sunglasses and a tight black bandana pulled low on her brow. I can see very little of her face, but it’s clear she’s livid.

“Fake news are ya?” she barks, before launching into a rant about something called Nuremberg 2.0, when all the doctors and politicians are going to go on trial for the “fake pandemic”. Journalists will be first to hang, apparently. She thrusts her face at me. “Make sure ya write that Avi tells the truth.”

Until recently, the far right was regarded by most people as a glitch, a virus in the software of society. There was the Dutch politician Geert Wilders, who proposed putting what he called a “head-rag tax” on hijab-wearing Muslim women; and Jean-Marie Le Pen of the French National Front, who once described the Holocaust as “just a detail” of World War II. In Australia, meanwhile, activists fumed about halal food and Asian migration. But they were on the fringe. Way out there. Virtually over the horizon.

“The Australian extreme-right’s false claims of implausible government conspiracies come from the playbook of Trump and his associates.”

Then along came Donald Trump, and the fringe began moving towards the middle. “Donald Trump used his platform as [US] president to promote extreme-right figures and their ideas, and give them a veneer of legitimacy,” says Bill Browne, director of the Democracy and Accountability Program at the Australia Institute, a public policy think-tank. “The Australian extreme-right’s false claims of hokey COVID remedies and implausible government conspiracies come from the playbook of Trump and his associates.”

Among the most durable of Trump’s conspiracies concerns “fake news”, the idea, supercharged by the pandemic, that traditional sources of information, whether they be newspapers, television or the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation, cannot be trusted. Rising in their stead, like mushrooms after rain, have come a cohort of self-described truth-tellers – YouTubers, vloggers, bloggers and podcasters – whose motivations run from blitzkrieg-scale culture war to flat-out grifting and malignant narcissism.

One of the most successful of these is Avi Yemini, who, depending on his mood or the demands of the moment, can fit into any one of the above categories or a mixture of all of them.

After the Binary protest we repair to the Elephant and Wheelbarrow pub in Bourke Street for lunch, where Yemini orders a large plate of meat and gravy. An avid carnivore, he regards vegetarianism, whether for animal rights or climate-change reasons, as pointless virtue-signalling. (“Saving the planet one vegetable at a time.” ) He then reviews the morning’s footage.

“I wasn’t expecting much from the Binary thing but it was actually quite decent.” In coming days, he’ll post a report on the protest across his social media platforms, where he has 1.6 million subscribers, including on Telegram, Twitter and YouTube.

It’s been a busy time for Yemini. Just days prior, he’d been stopped from entering New Zealand, where he’d planned to cover an anti-government protest. New Zealand authorities said they rejected Yemini on character grounds, citing his conviction for domestic violence.

Soon afterwards, Yemini went on Australian TV with conservative commentator Andrew Bolt and argued his offence wasn’t sufficient grounds for refusal. Now he and Bolt were being attacked on Twitter by Grace Tame, former Australian of the Year and sexual abuse survivor, for minimising domestic violence.

“It’s a joke,” Yemini says. “People call me a wife-basher, but my conviction was the most minor one you can have. It was a $3600 fine, which was less than a breach of COVID!” Besides, “the actual charge says I threw the chopping board and it hit her, not that I threw the chopping board at her.” I’m tempted to tell him this sounds an awful lot like he’s … minimising domestic violence, but he’s moved on, phone in hand, and is busy scrolling through Twitter.

Avi Yemini grew up in St Kilda East, in an ultra-Orthodox Jewish home of 17 children. (He was number 10.) His father, Zephaniah Waks, was a Jew of Russian/Polish extraction, while his mother, Haya Yemini, was born in Israel to Yemeni parents. (Avi assumed his mother’s name around 2012, saying he identified more with his Middle-Eastern heritage.) Zephaniah was a computer consultant who considered procreating something akin to a religious duty, and who brought his children up with a stern but loving hand. Theirs was a frugal home: “Mum is a great bargainer – she’s Middle Eastern!” Manny Waks, Yemini’s older brother, tells me in an email. “She bought in bulk and seasonal products, and received family discounts at school and community programs.”

Yemini went to the nearby Yeshivah College. “We went to prayer three times a day,” he says. “We were so cut off from the world.” At 14, he started partying and doing drugs: MDMA, speed, ice. His parents packed him off to a series of ultra-Orthodox schools in the US, Israel and Brazil, where one of his older brothers worked as a rabbi. By 16, he was back in Melbourne, where he promptly got hooked on heroin. “He was in terrible shape,” Manny tells me. “I used to go and pick him up from the gutter.”

Zephaniah wouldn’t allow his son to come home until he’d quit drugs, so Yemini bounced around for the next two years in foster homes, crisis care and rehab. At 19, in an effort to straighten out, he joined the Israel Defence Forces, where he served for three years as a marksman, mainly in Gaza. (His opponents say he shot Palestinian children; Yemini denies this, saying that he only ever engaged in combat with adults.)

Yemini in 2006, during his time with the Israel Defence Forces.Credit:Courtesy of Avi Yemini

In 2009, Yemini returned to Melbourne, where he started a gym with his then wife, in Caulfield, called IDF Training. (He set up another in the CBD five years later.) The gym specialised in krav maga, a form of martial arts used by the Israeli military. When the writer John Safran visited IDF Training for his 2017 book, Depends What You Mean by Extremist, he found punching bags shaped like people dangling from the ceiling.

Yemini offered to burn a Palestinian flag as “colour” for Safran’s book – Safran declined. The gym attracted attention in 2015 when it began offering a live weapons training course called “Intro to Israeli Tactical Shooting”. (Yemini sold the gyms in 2018.)

“At that stage I wasn’t political,” Yemini tells me. “But then I saw a report on the ABC about Gaza, and the bullshit way they twisted the narrative to make Israel look bad.”

Yemini began blogging on the gym’s Facebook page, where he vented about what he saw as the ABC’s left-wing bias and the situation in Israel. “Some people got angry and left the gym, but I didn’t care. It created controversy, and I enjoyed the discussion.”

In 2015, he started his own Avi Yemini Facebook page. He says he was “mainly talking shit” but he liked “the idea that people were sharing my mind and listening to me”. He understood instinctively that the best way to build a profile was to create controversy.

“The more confrontational posts were the ones that were successful. And so that’s what I did.”

In 2016, he invited One Nation senators Pauline Hanson and Malcolm Roberts to an open forum in Melbourne to discuss the “dangers” of Muslim migration. (The event was cancelled after opposition from Jews Against Fascism.) When commentator Waleed Aly criticised then immigration minister Peter Dutton’s comments that Lebanese immigrants should never have been let into Australia in the 1970s and ’80s, Yemini took to Facebook, calling Aly a “POS” (“piece of shit”) adding that it was “time to send him home”. (Aly was born in Melbourne.)

In 2017, Yemini headed up a Trump-esque “Make Victoria Safe Again” rally, claiming that break-ins and carjackings by “gangs” – code for African youths – were out of control. (Data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics shows that from 2008 to 2016, most crime rates in Victoria decreased.)

Yemini with Pauline Hanson in rural Victoria during the last federal election. Credit:Courtesy of Avi Yemini

Living off the money he made from his gyms, Yemini set about becoming a “brand”, much in the mould of Alex Jones, the American alt-right radio host and conspiracist (who was last year ordered to pay more than $US1.4 billion to the families of victims of the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School mass shooting for spreading lies about the killings). Then, in 2017, he got a job as a content creator for the far-right fringe party, the Australian Liberty Alliance, then led by Kirralie Smith (latterly of Binary). In 2018, he ran for the ALA as an upper house candidate in the Victorian state elections but received just 0.48 per cent of the vote.

By this time, Yemini was posting increasingly merciless material on social media. In 2018, when Invasion Day activist Tarneen Onus Williams said she hoped Australia “burns to the ground”, Yemini demanded on Facebook that she be stripped of her Australian citizenship and given “a little piece of land in the bush – with none of the Western luxuries. Let her work the land and hunt for her grub.” When journalist Osman Faruqi complained about Australians not being able to comply with the plastic bag ban, Yemini published his phone number on Facebook, and encouraged his 150,000

followers to give Faruqi a piece of their mind. (The post remained up for 18 hours, during which time Faruqi received multiple death threats and abusive messages.) Within a week, Facebook had permanently deleted Yemini’s page.

Not that it mattered. By 2019, Yemini was a fixture in the far-right media, with a thriving social media presence and regular guest slots on The Bolt Report and Mark Latham’s TV program, Outsiders. When I ask about his style back then – the trolling, the abuse, the doxxing – he shrugs. “I wouldn’t do it again,” he says. But back then, “the more confrontational posts were the ones that were successful. And so that’s what I did.”

We’re driving through the city in Yemini’s Honda Civic, heading to North Melbourne. We’re going to meet Rukshan Fernando, aka the Real Rukshan, a fellow YouTuber with whom Yemini had attempted to travel to New Zealand a week before. Yemini often works with Fernando, who became well known during the pandemic for live-streaming anti-lockdown protests and what he saw as a heavy-handed response from Victorian police. Fernando’s sympathetic coverage of the protests and his coded anti-vax talk made him a folk hero among COVID denialists and anti-lockdowners, who would chant his name whenever he showed up at rallies, and even offer him cash. When we pull up outside Fernando’s place, Yemini turns to me, and says, only half joking: “Now remember, your story is about me, not him.”

Fernando’s office is studiously nondescript; a chipped red-brick facade, windows blocked out with reflective coating, and a door that’s hidden down a side entrance. Inside, however, is a state-of-the-art production facility, with great stacks of sound and editing equipment and expensive-looking cameras and hard drives, and the biggest, widest wide-screen computer terminals I’ve ever seen. The son of Sri Lankan migrants, Fernando has a successful business in wedding videography but now spends most of his time producing YouTube videos imploring supporters to feed the “fire of freedom” and comparing public health officials to Hitler. He has 270,000 Facebook followers and 37,800 YouTube subscribers, but insists he doesn’t make a cent from social media. “My wedding business is going good, and that’s how I support myself.”

As Yemini and Fernando discuss their next video, I wander about the studio, eventually coming to a shelf full of Trump memorabilia, including Trump playing cards, a carved wooden Trump doll, and a beer stein shaped like The Donald’s head. “I’m a big fan,” Fernando tells me. “He puts his country first. In Asia, we don’t look down on people who put their country first. There’s nothing remarkable about that.”

But what about the Capitol riot? “The police let people into the Capitol. There’s plenty of videos of that. All they were doing was walking around and they got arrested.” Okay, so what about how Trump ignored climate change? “It’s all down to interpretation,” says Fernando. “We’ve seen with COVID how science can be interpreted in different ways.” Yemini (who is vaccinated) sniggers. “Get Pfizer to create a vaccine for climate change.”

After a time, Yemini and Fernando get talking about their recent trip to New Zealand. Yemini had been blocked at Australian customs from entering but Fernando had got in, and filmed a glowing tribute to an anti-government rally led by Chantelle Baker, a COVID conspiracist who ran NZ Testimonials, one of New Zealand’s largest anti-vax Facebook groups, before it got shut down in 2021. Yemini insists that being banned was a bonus. “They did me a favour,” he says. “I didn’t have anything in New Zealand, now my [NZ social media] audience has quadrupled.”

Plenty of publications crowdfund their operations, but Yemini has made it an art form.

It was also a nifty fundraising opportunity. Immediately after being banned, Yemini urged his followers to donate to a legal challenge, “so Avi can provide real, on-the-ground reporting and ask the questions NZ media refuse to ask”. It soon emerged that his donations page had been registered the day before his flight, fuelling speculation he always intended to get turned back. Yemini concedes the page was set up before his trip, but says it was done as a “precaution”, to prepare for the possibility of a ban. (When I ask later how much was raised, he refers me to Rebel News CEO Ezra Levant, who tells me in an email, “the exact sum is private for competitive reasons.” )

Plenty of publications crowdfund their operations, but Yemini has made it an art form. Indeed, his reportorial approach – YouTube celebrity meets paranoid-tabloid – is perfectly tailored to the attention economy, where social-media algorithms reward confrontation. He often attends protests, where he will pester police and/or protesters until he gets arrested or assaulted. This will all be filmed. He then posts this footage to his YouTube channel, where his duly enraged fans are invited to “contribute” so that he can be free to attend the next protest … where he will repeat the entire process.

This could be mistaken for a business model. But Ezra Levant sees it differently. “We do not work for an oligarch like Rupert Murdoch or a large corporate conglomerate like Nine [publisher of Good Weekend]. Crowd-funding is an important way for a little outfit like ours to level the playing field with mighty competitors and opponents.”

Yemini says he needs the money for his legal bills, which can be “f—ing expensive, like $1 million a year”, some of which is spent on a seemingly endless schedule of court actions, including one in 2020, in which he took Victoria Police to court for false arrest and won. He adds that he doesn’t get any cash from the donations, and is paid a salary by Rebel.

Yemini in 2020, being detained by Victoria Police during an anti-lockdown rally. He later sued them for false arrest and won. Credit:AAP

The problem with profiling Avi Yemini is that there are so many Avi Yeminis. There’s Avi the “freedom fighter”. Avi the “independent journalist”. Avi the propagandist. It can get confusing, even for Avi. He wonders aloud why people don’t take him seriously, then admits that much of what he does is “putting out a persona”. He says he hates “victims” but whinges for 20 minutes straight about how The Age [one of Good Weekend’s host mastheads] only “wants to make me look bad” and “pretends that I don’t exist” and how it didn’t report on his successful legal action against Victoria Police. “I won! The cops had to apologise to me! But did The Age write that? NO!”

We’re driving from Fernando’s office to Berwick, in Melbourne’s south-east, where Yemini lives with his wife, Rhonda, a hairdresser he met at a coffee shop in 2018, and their cavoodle, Winnie (after Winnie-the-Pooh). The traffic is terrible and it’s raining and his Google Maps is playing up, but none of that matters because he’s triggered himself about The Age.

“The guys at The Age, they’re so morally superior,” he says, talking at the windscreen. “They think of Avi Yemini as a lower breed. They look down at me. They’re academics, right, but they’re just jealous. They studied all their lives and toed the line and did everything they’d been taught and then they see me and I’ve skipped all that and gone and done it [journalism], and not only am I doing it but I’m doing it better than they are.” He takes a breath. “During COVID lockdown, A Current Affair began copying my tactics.”

There may be another reason mainstream media have been wary of Yemini: namely, his affiliation with neo-Nazis. There’s always been a degree of crossover between Australia’s white-supremacist fringe and Yemini’s Islamophobia and anti-immigration rhetoric. Neo-Nazis groups have attended his public events and promoted them on their websites. In return, Yemini has spruiked their events, including a charity “homeless feed”, in 2017, held in Melbourne by the Soldiers of Odin, a self-proclaimed vigilante, white nationalist group.

When the government threatened to deport Swiss man and Soldiers of Odin member, Jan Herweijer, in 2017, for posting anti-Islamic material and links to terrorism on his Facebook page, Yemini started a change.org petition to have him remain in Australia. (Herweijer denied any wrongdoing; the government won’t tell me if he was ultimately deported, citing privacy concerns.)

In 2017, when Melbourne man Chris Shortis was convicted of racial vilification for helping stage a mock beheading in Bendigo to protest the construction of a mosque there, Yemini showed up at court and shook his hand. He now regrets the handshake. “I misjudged it,” Yemini tells me. “It was just a natural human reaction. But now, if I met a person like him, I wouldn’t shake his hand, because he is a Jew-hater.”

Yemini is moved on by police during a counter-protest against anti-vaxxers, the far-right and fascism in Melbourne in 2021.Credit:AAP

There have been similar misjudgments. In 2017, he appeared on stage at an event in Sydney with Milo Yiannopoulos, the British alt-right political commentator who has been accused of promoting violence and hate towards Muslims, and who has justified having sex with young boys. Yemini insists he doesn’t advocate sex with young boys; he just believes “everyone has a right to free speech.”

A year later, Yemini appeared at a rally in London in support of Tommy Robinson, another British alt-right Islamophobe, where he told the crowd he was the “world’s proudest Jewish Nazi”. Yemini now says this was an “obvious joke. I was saying it ironically, making a point about not accepting the labels that other people put on you.” I ask if the “joke” could be regarded as dangerous. “No. What’s dangerous is the weaponisation of language, so that the use of the word Nazi by the left doesn’t mean anything any more.” (The Executive Council of Australian Jewry tells me in a statement that Yemini doesn’t “in any way represent the Australian Jewish community or mainstream Jewish thought”.)

“He’s exploiting people who are genuinely scared about COVID and the lockdowns. They are already vulnerable, and he makes them feel legitimised in taking extreme action.”

Yemini’s bromance with neo-Nazis is “all transactional”, according to Andy Meddick, from the Victorian Animal Justice Party, who has spoken out in state parliament about far-right extremism. “Avi takes advantage of that anti-vax freedom-fighter movement, and then the white supremacists see him reporting on these protests in a sympathetic way, and they look at the comments that people make on his stories, and they would have thought, ‘Okay, look at all these potential recruits.’ Meanwhile, Avi also gets some of their audience.”

Meddick, who was sent death threats in 2021 when he helped pass Premier Andrews’ pandemic legislation, believes Yemini is dangerous. “He’s exploiting people who are genuinely scared about COVID and the lockdowns. They are already vulnerable, and he makes them feel legitimised in taking extreme action.”

Yemini’s brother Manny Waks joins us for lunch at Laffa Bar. Waks and Yemini have a complicated history: in 2016, Waks sued Yemini for defamation after Yemini accused Waks and their parents of harbouring a known paedophile in their home. For Waks, who was abused as a 13-year-old by a security guard at the Chabad Yeshivah Centre in Melbourne, this was particularly offensive. The case became big news in the city’s Jewish community. A couple of months later, Yemini apologised and Waks dropped it.

“We’re reconciled now,” says Waks, an advocate for Jewish abuse victims. “Our politics are very different. I’m centre-left and pro-human rights, and people view Avi as a thug and anti-human rights. But I still love him.”

Waks, who is 10 years older than Yemini, is tall, lanky and refreshingly unfiltered. He and Yemini order meat skewers, and I get a vegetarian sinia, with layers of cauliflower smothered in warm tahini. When it arrives, I offer Waks some. He rejects it politely, stating that the tahini resembles ejaculatory fluid. “Seriously. No tahini. No hummus. No mayo. I’m a very fussy eater.”

Yemini, left, with two of his 16 siblings, from left, Levi Waks and Manny Waks.Credit:Courtesy of Avi Yemini

He is similarly candid about his brother, whom he begins discussing fondly, but at a certain remove, as if he’s not with us at the table. “Avi’s an agitator, a provocateur. That’s what he does. I’m actually surprised he’s so articulate because he couldn’t string a sentence together when he was young. But I’m yet to be convinced that he believes a lot of what he does.”

“Really?” says Yemini.

“He jumps on bandwagons,” Waks continues, looking at me. “He jumped on the anti-Muslim bandwagon, and it worked for him. Then he moved on to crime and COVID. And it motivated hordes of supporters, and so, you know, good for him.”

I mention the neo-Nazi stuff. “I went to their court cases,” says Yemini, “but it was about free speech.“

“But the impression was that you were courting neo-Nazis,” Waks says. “You went to the court cases because you thought it was a high-publicity event and you wanted to capitalise on that.” Waks goes on: “You pick and choose your human rights, who they apply to, whose human rights you choose to fight for.” Yemini sighs. But Waks hasn’t finished. “Also, you’re seen as instigating stories. Like you become the story, rather than reporting on it.”

“What do you want me to do? If I become the story, I still report the story.”

We eat some more. Waks leans back in his seat. “I think once Avi progresses in life he’ll realise what’s important to him. And hopefully he’ll start doing something that’s less opportunistic, and succeed there.”

Yemini stares at his brother, but says nothing. Talk then turns to their family; what this or that sibling is up to. Within 10 minutes, we’ve finished our meals. As we get up to leave, a cop car drives past, lights flashing, sirens blaring. “Oh, look, Avi,” I say. “It must be an African gang!”

Yemini looks sheepish. “You can joke, but it was true. Every night there were home invasions.”

Waks just laughs.

Support is available from the National Sexual Assault, Domestic Family Violence Counselling Service at 1800RESPECT (1800 737 732).

To read more from Good Weekend magazine, visit our page at The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age and Brisbane Times.

Most Viewed in National

Source: Read Full Article