By Heath Gilmore

Bundjalung elder Uncle Lyle Roberts at a Land Rights workshop at the Aquarius Festival in Nimbin, in northern NSW, in 1983.Credit:Juno Gemes

Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

The old man in a hat and jacket ordered them to leave. Uncle Lyle Roberts stood before a long makeshift plank table at the campsite and gestured to the hairy young ones and important visitors to go away. “To the trees and wait for us,” he instructed them.

Fifty years ago, in the hills of Nimbin, up to 100 white people including Leila Wedd and Al Oshlack, and a group of Indigenous people, were hiding in the scrub near a big campsite clearing, watching and waiting.

“We stood there as the sun set,” Wedd said. “Uncle Lyle’s voice was rising [back at the main campsite]. We began to cry. The sound of clap sticks reached us, or perhaps the women clapping in the lap. And the rhythms built and built and this marvellous calling out.”

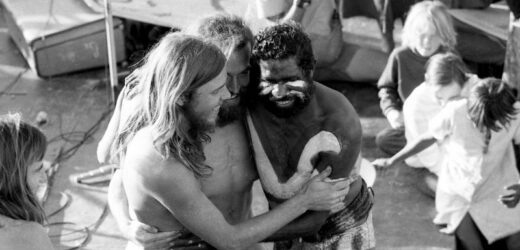

A group embrace after an Indigenous dance performance by the Mornington Island group.Credit:Chris Meagher

Roberts, a Bundjalung elder and one of the last known initiated men of the area, summoned them to return.

He divided the men and women to sit on the ground, on either side of him, and welcomed them. He talked for some time about his people, about reconciliation and equality, and the significance of the approaching millennium for healing. That this was a turning point.

Ever wondered why Australians pay tribute to Indigenous people before weddings, sporting matches, zoom meetings or simply when your plane lands?

Usage of the custom, known as an “Acknowledgment of Country” and “Welcome to Country”, has been building for decades, particularly leading up to the Indigenous Voice to parliament referendum this year.

Somehow, a bunch of hippies and university students, better known for shedding their clothes and a voracious appetite for marijuana, magic mushrooms and acid, played a role to help usher these customs into the mainstream.

The festival was described by acclaimed poet David Hallett as “a cross between, between a boy scout camp and being on LSD, it’s really both of them strangely”.Credit:Chris Meagher

It is believed the 1973 Aquarius Festival in Nimbin, outside Lismore in northern NSW, was the first time white people sought permission for the use of the land from the traditional owners.

On Friday, Aquarius50 – a 10-day celebration of the original festival, which established Nimbin as the alternative lifestyle capital of Australia – kicks off by acknowledging the bond between rainbow fellas and black fellas.

In Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities had ceremonially welcomed each other for thousands of years before British colonists arrived in 1788.

Indigenous travellers crossing into someone else’s country were required to send a request to the land’s people to be granted permission to enter. This also required the visitor to acknowledge, adhere to and respect the rules of the country that was being entered.

Aquarius Festival director Graeme Dunstan and traditional custodian Bundjalung elder Uncle Cecil Roberts who was 16 at the first festival, pictured at The Hemp Embassy in Nimbin.Credit:Elise Derwin

The original festival directors Johnny Allen and Graeme Dunstan, who were employed by the Aquarius Foundation, the cultural wing of the Australian Union of Students, knew nothing about this history.

Allen says most white people of his generation had never seen an Aboriginal person, even at university.

He says the lead-up to the festival was full of misunderstandings, ignorance, febrile racial politics, frantic last-minute negotiations, fears of an Indigenous curse and concerns about holding an event near Nimbin Rocks, an extremely significant cultural site and initiation ground.

He says the Black Power Movement, including Gary Foley and Dennis Walker, took the Aquarians to task repeatedly, especially over their initial failure to ask permission from the traditional owners.

“We were clueless and a little bit clumsy with no understanding about Aboriginal ways and protocol. But I think our hearts were in the right place,” Allen says.

After the initial mistakes, Dunstan led a delegation to Woodenbong to meet local elder Uncle Lyle. Others in the Aquarius Foundation orbit took it upon themselves to meet the elders, too.

Researcher Alethea Scantlebury says Bauxhau Stone, an African Kalahari bushman who joined the festival team, and had worked with Indigenous groups in central Australia, played a crucial role in building bridges.

Scantlebury said Stone travelled widely, making arrangements for Indigenous dance groups and artists from across Australia to travel to Nimbin and began mobilising the local Bundjalung communities, reassuring them ceremonies were being conducted by respected elders. That they would be welcome.

"Most Australians know they’re on Aboriginal land," says Rhoda Roberts.Credit:Paul Harris

Leading Indigenous arts figure Rhoda Roberts remembers her father, Pastor Frank Roberts, coming home from the festival believing a new era was awakening, with young white people respecting the land and wanting to learn from local custodians.

Years later Rhoda Roberts coined the term Welcome to Country.

“I thought after Aquarius and the Terania Creek protests that maybe there’s an opportunity for the rest of Australia to have this respect for and care for country, and that’s when I used the term Welcome to Country to start exhibitions or productions for the Aboriginal National Theatre Trust in the 1980s,” she said.

“Now that Australians have accepted the acknowledgment, they are ready for the next layer.”

The Morning Edition newsletter is our guide to the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in National

Source: Read Full Article