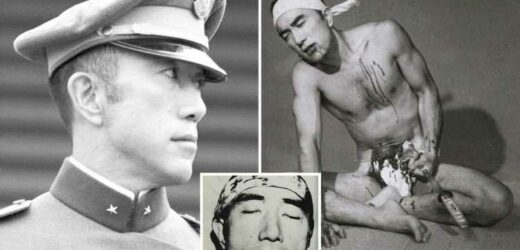

A JAPANESE militia leader disembowelled himself and ordered his own beheading in a ritual suicide after trying to seize power in a failed coup.

Yukio Mishima attempted to rally the army to overthrow the government in one of the most infamous incidents in the history of Japan.

And when the coup attempt didn't work, Mishima committed "seppuku" or "harakiri"- a form of ritual suicide which was a key part of historic samurai culture.

Even the suicide attempt went wrong however, as a friend who he had ordered to cut off his head failed to do so three times.

Instead another member of the militia had to step up and finish the job – finally chopping off Mishima's head.

But before he was an attempted revolutionary leader, Mishima was a celebrated author known as "the Japanese Ernest Hemingway".

His works are regarded with awe to this day – despite his shocking end as he attempted to tear down the new Japan which had been rebuilt after World War 2.

Known for his books, films and poetry, he became increasingly political in his later years – establishing a civilian militia group called the Tatenokai, or the Shield Society.

Most read in News

'not a bad boy' Mum DEFENDS thug son who left girlfriend Angel disabled in shock statement

'Scruffy' Andrew told cop to 'f*** off' after HE sparked security scare

Chilling moment rapist carries woman along the streets before attack

Comedian Joe Lycett sparks chaos after 'leaking' Sue Gray report on Twitter

After the war, he became increasingly frustrated with life in Japan – with the country reimagined as a more Western culture following its surrender to the US in 1945.

He openly campaigned for the scrapping of Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution – which outlaws wars to settle disputes.

And he became obsessed with restoring absolute power and godlike status to the Emperor of Japan.

The author was also known to have a morbid fascination with death, even participating in photoshoots depicting his own brutal demise.

Mishima spoke of having samurai ancestors and how Japan had lost its "samurai spirit" after the global conflict.

He said: "After the war, our brutal side was completely hidden – but I believe it is just hidden.

"I don't like how Japanese culture is represented only by flower arrangements – a peace, loving culture.

"I think we still have a strong warrior's mind."

In 1967, using his connections within the Japanese Army Mishima underwent basic training, insisting he wanted to experience "real" military life.

Where has the spirit of the samurai gone?

He had to use his birth name Kimitake Hiraoka as the army did not want to be criticised for giving a non-soldier special treatment.

The following year, he formed the Shield Society comprising of a small band of right wing college students who were sworn to protect the Emperor.

Then, on November 25, 1970, Mishima and four members of his group attempted the military coup at Camp Ichigaya, a base in central Tokyo.

read more on the sun

NEW YEAR FEAR Boris Johnson says Xmas is ON – but NYE looks doomed as Omicron cases soar

Rylan Clark reveals bitter feud with top actor he wanted to 'punch in the face'

Drink driver, 23, who crashed Mercedes claimed kerb was 'too high'

Katie Price planning to 'name & shame' enemies in new tell-all book – her EIGHTH

They had arranged to meet commandant Kanetoshi Mashita but while inside his office barricaded the room and tied the military chief to a chair.

Wearing a white headband with a red circle in the centre, Mishima walked out onto the office's balcony and as soldiers began gathering below he read from a pre-prepared manifesto.

In his speech, he said: "Where has the spirit of the samurai gone?"

However, rather than rise up and join his cause, the soldiers reacted with hostility and began booing him.

Mishima finished by shouting "Long live the Emperor" three times before retreating back into the office.

After his carefully crafted speech failed to rouse the troops, Mishima returned to the office and committed ritual honor suicide

After Mishima disemboweled himself using a blade to the stomach, his second in command – and rumoured lover – Masakatsu Morita then tried and failed three times to behead him.

He was using 17th century samurai sword bought by the author for 100,000Yen – about 390,000Yen or £2,600 in today's money.

Another member of the group Hiroyasu Koga, who was a champion of 'kendo' – a martial art involving bamboo swords – then stepped in and cut off Mishima's head with the blade.

According to the testimonies of the surviving coup members, Morita also dropped to his knees and plunged a sword into his abdomen saying "I can't let Mr. Mishima die alone."

Koga once again grabbed the sword and cut off his friend's head. He and the other coup members were jailed for four years for "assisting a suicide" and "illegal possession of firearms and swords".

Before Mishima's death, no one in Japan had killed themselves by seppuku since World War 2.

Japanese philosopher Hide Ishiguro, writing in The New York Review five years later, explained how the suicide was interpreted in Japan.

He said: "Some thought he had gone mad, others that this was the last in a series of exhibitionistic acts, one more expression of the desire to shock for which he had become notorious.

“A few people on the political right saw his death as a patriotic gesture of protest against present-day Japan.

"Others believed that it was a despairing, gruesome farce contrived by a talented man who had been an enfant terrible and who could not bear to live on into middle age and mediocrity.”

Mishima was fascinated with suicide and would act it out with lovers in role play.

He performed ritual killings in three different films and again acted out Harakiri in a series of photos in November 1970 – days before his death.

Speaking about the use of ritual suicide in his work, he said: "I wanted to revive some 'samurai spirit' through it.

"I don't want to revive Harakiri itself but through a very strong vision of Harakiri I wanted to inspire and stimulate younger people.

"Through such a stimulation I wanted to revive some of sense of honour and responsibility – some sense of death in honour. That's my purpose."

Source: Read Full Article