Eliza Robbins-Brown experienced heartbreak for the first time at age 19.

In May 2017, Eliza, who has a neurodegenerative condition called ataxia-telangiectasia, which means she has minimal verbal communication, lost her brother, Jayden — one of the few people she felt understood her.

Her 22-year-old brother cared for her about 20 hours of the week. This involved dressing her and going on outings, including their favourite activity: seeing the miniature trains at Diamond Valley Railway.

Eliza Robbins-Brown with her TAC-funded dog, Harmony.Credit:Justin McManus

Their bond was intense and rare. Jayden was the only person Eliza let hug her aside from her mother.

But when police showed up on Eliza’s doorstep with news that Jayden had died in a road accident after a driver failed to give way, something died inside her.

“Everything changed after that,” says her mother, Louise Robbins.

Eliza suffered silently as the weeks and months rolled on. She became fixated on the comings and goings of her family members, needing constant reassurance they would return home. She searched for traffic accidents on the internet.

She would wake in the middle of the night and roam around the house, checking windows and doors and looking in her brother’s bedroom.

She would be in the middle of a task and be struck by a memory of her brother, causing her to explode in a fit of tears.

“It was just utter devastation. You couldn’t comfort her. She would just be in her room, her heart broken, and there was nothing you could do,” Louise says.

But it was Eliza’s sudden interest in dogs that opened a path for her to begin moving forward in her grief.

Eliza cries far less now she has Harmony. Credit:Justin McManus

A team of five carers and a psychologist — support that had been secured under the National Disability Insurance Scheme months before Jayden’s death — tracked how Eliza was doing.

A year after Jayden died, they noticed a change. Eliza stopped fearing dogs and was now reaching out for pats and begging to go to the dog park, where she would lie on the grass giggling as several of the animals rolled over her.

”Even though she can’t communicate, she got across to us what she needed,” Louise says. “She was lonely.”

The family understood Eliza needed a therapy dog, but it would cost them $30,000 — money they didn’t have.

They raised $10,000 and looked to the Transport Accident Commission for the rest.

Their lawyer from Maurice Blackburn, Voula Lambropoulos, SC, was determined to help, but she knew their application was unusual.

“The TAC is very conservative,” she says. “They have a list of treatments they approve regularly … but whether you’ve approved it before or not is not the test. It’s whether we fall into Section 60 of the Transport Accident Act 1986.”

The TAC rejected the Eltham family’s first application for a dog, which medical professionals recommended as a treatment for Eliza’s post-traumatic stress disorder caused by her brother’s sudden death.

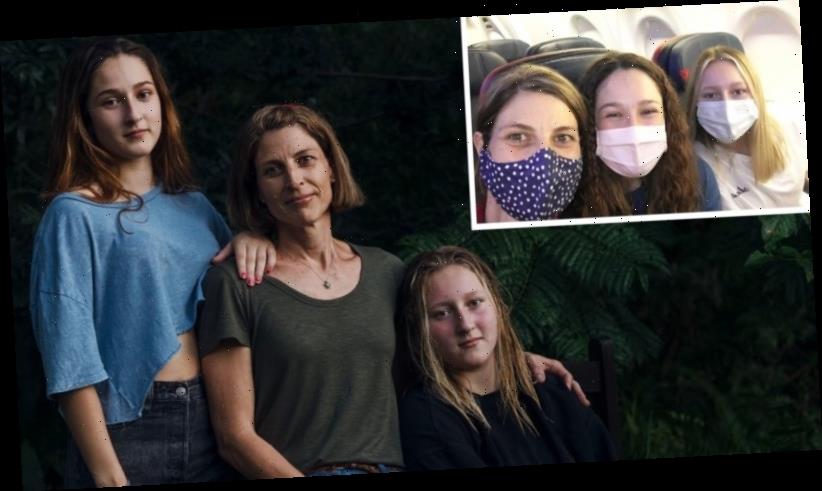

Eliza with her brother, Jayden, who cared for her before he died in a road accident.

But the family was successful on appeal. It was the first time the TAC had funded a therapy dog for someone affected by road trauma.

More than two years later, Harmony, a black labrador trained for 18 months at assistance dog trainers Smart Pups, licks Eliza’s face to wake her up every morning.

Eliza merrily chats to Harmony over breakfast and bids her a theatrical goodbye before going off to have a shower — even though the dog waits for her outside the shower door.

She takes Harmony to the cemetery to visit Jayden’s grave (she couldn’t face the grave site previously). She eats her lunch there and talks to Harmony about Jayden.

Eliza no longer roams the house for Jayden. She cries far less frequently. Her mother says she is happy.

“A hole has been filled,” Louise says.

While research into the effect of dogs on PTSD sufferers is limited – and especially for sufferers who also have an intellectual disability – Meaghan O’Donnell, head of research at Phoenix Australia, which focuses on trauma-related mental health, says there is room for agencies such as the TAC and the Veterans’ Affairs Department to consider the benefits for some people.

There is evidence to suggest that where first-line psychiatric treatments have proven ineffective, a service dog can enable functional and social improvements, helping the PTSD sufferer to overcome loneliness and confront situations that might trigger a trauma response, Dr O’Donnell says.

Louise says more research and funding is needed for alternative treatments such as therapy dogs to help those affected by trauma.

“The whole idea of alternative therapies and holistic approaches is gaining momentum, but there’s still a long way to go for it be accepted as a legitimate therapy by the TAC and insurance companies,” she says.

“I didn’t want Eliza to be medicated so she doesn’t feel. That’s not healing, that’s not processing. She needed to grieve, because she loved her brother. She just needed to do it her way.”

Start your day informed

Our Morning Edition newsletter is a curated guide to the most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article