The terrifying day ITV’s man in Buenos Aires was abducted by a hit squad under orders to execute 500 British expats…and how, in an amazing twist 40 years on, JULIAN MANYON discovered the identity of his chief kidnapper in a secret CIA file

The words were in Spanish but even with my fragmentary knowledge of the language, I could understand them. ‘Quiet,’ the harsh voice said, and then with a short gesture of the pistol: ‘When we get where we are going, I will kill you with this.’ It was May 12, 1982, and in the jargon of the Argentine secret police, I had been ‘swallowed’ and ‘walled in’.

As the car rolled forward at a deliberately steady pace, I lay constrained and helpless on my back in the rear footwell, a cloth over my head blocking almost all vision, a man’s knee jammed against my neck, pinning my head against the back of the seat in front and a hard, tanned hand holding an automatic pistol pressed against the side of my head.

One thing was very clear: the three men who had seized me and who now held my life in their hands were professionals in the art of kidnapping.

A woman tries desperately to prevent detention of a young man by police during anti-government rally in Buenos Aires during the last days of Argentina’s Dirty War

Forty years ago, in May 1982, the eyes of the world were fixed on events taking place at one of the most remote and obscure points on the planet: the Falkland Islands, the South Atlantic archipelago that had been under British control since 1833.

Together with a crew from Thames Television’s current affairs programme TV Eye, I was filming a report in war-torn El Salvador when the telephone call came from our editor in London. His instructions were brisk. Some Argentinians had landed on a British-owned island. It was becoming an international crisis. We should head for the Argentine capital, Buenos Aires. ‘Try to keep out of trouble,’ he said, helpfully.

As the British task force sailed towards the Falklands – or Las Malvinas, as the Argentinians call them – to reclaim them, the pugnacity of the Argentine junta surprised many who did not know the recent history of the country. These were men who already had much blood on their hands.

They had ordered the torture and often murder of thousands of Leftist subversives whom they had kidnapped on the street or dragged from their homes. It was known as the Dirty War, an operation against many of their own people, which had extended into brutal suppression of every vestige of opposition in Argentina.

General Jorge Videla had seized power in 1976 in the sixth military coup that Argentina had experienced since 1930. As the junta promised to restore stability, their security forces were stepping up the already brutal campaign against the insurgent threat. Now they set up what can only be described as a killing machine which dealt with its victims with frightening efficiency, turning them into a legion of the ‘disappeared’.

A group of demonstrators are held by police during anti-government rally in Buenos Aires during what would be the last days of Argentina’s Dirty War

It was a ruthless struggle in which a particularly murderous branch of the security forces was led by a violent career criminal who had carried out one of the most spectacular bank robberies in Argentina’s history and who joined the secret police directly from prison.

He had been given the power of life and death over the perceived opponents of the junta. Now that included me.

IT WAS early afternoon when, together with the other members of our British team, I emerged from the Argentine foreign ministry in Buenos Aires after a failed attempt to interview Minister Nicanor Costa Mendez, the Oxford-educated civilian described by some as the ‘evil genius’ of the junta, or military regime.

Costa Mendez had been angered by my questions and brushed us off with an infuriated wave of the hand. Minutes later, as we got into our car, another car cut in front of us, forcing us to stop, and disgorged strongly built men clad in sharp suits. They seized me with firm hands while shouting: ‘Police!’

Suddenly I was propelled into the back of their vehicle. The doors slammed shut and in a motion that immediately terrified me, the men produced what appeared to be custom-made leather thongs with which they expertly tied the door handles to the door locks.

As I dimly realised amid the shock and mounting fear, this made it virtually impossible for me to kick open a door. It was a practised routine which these men had clearly carried out many times before.

Resistance was beyond my power and would, in any case, have been futile and probably fatal

‘Look,’ I said in broken Spanish-English to the man holding the gun to my head, ‘in my pocket I’ve got dollars. Please take the money and throw me out here.’ I felt a horny hand force its way into my trouser pocket searching for the money, some $800, which he silently removed. The car rolled on. When I made another attempt to speak, I was silenced with a slap, then my knees were struck with the pistol butt to make me pull them down beneath the level of the window.

Galtieri met Julian to apologise for the kidnapping, to aid his position in peace talks

But as my kidnapper scrabbled for the money, he had given me a brief glimpse of his face. I was too frightened to look at him calmly with a view to recall but something remained lodged in my memory all the same.

I had almost got used to the steady motion of the vehicle and my cramped position within it when it came to a sudden halt. We were in some sort of lay-by, and to my surprise Trefor, our sound recordist, was pushed into the car. We were made to sit next to each other on the back seat and told to be silent and keep our eyes closed. The car drove on into the countryside, then it stopped again. Brusquely we were shoved out and saw other cars with more gunmen, who were guarding Ted, our cameraman.

The sinister convoy had halted on the corner of a vast field. We were instructed in broken English to turn away from the gunmen, empty our pockets of our possessions and take off all our clothes except our underpants.

The three of us stood cold, almost naked and virtually numb with fear while the commander’s radio crackled sporadically behind us. Our kidnappers pointed a rifle at us and told us to walk down the road. We walked slowly and silently away from the gunmen.

Trefor was next to me and I found myself holding his hand. Behind us I heard the unmistakable double-click from the loading mechanism of the rifle.

There was no way to run and nowhere to hide. At any second the bullets would hit us and the light of life would go out.

Then there was another sound. It was the sputtering of a car engine starting up, then another, then a third. Wheels crunched on soil but we stood still, looking away, not daring to turn round. When we did, we were alone.

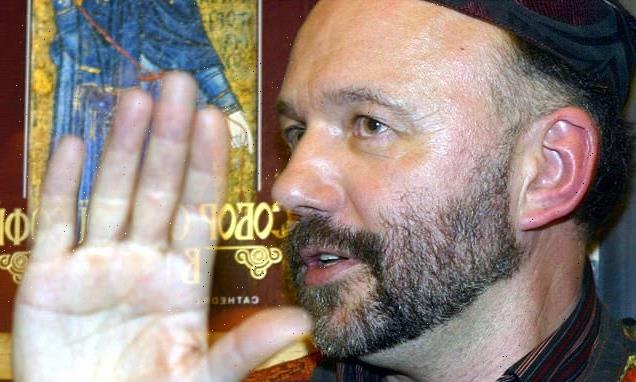

Kidnapper Anibal Gordon, a junta torturer

Instead of lying in pools of blood after the sort of execution that had taken place so often in Argentina, we were standing near-naked in a field, in the middle of a country at war with Britain. I think all three of us felt the same elation of survival. As emotion surged, we grinned and laughed and felt what can only be described as joy.

A farmer drove us to the police station in the nearest town, Pilar, where eventually a call to the interior minister, General Alfredo Saint-Jean, resulted in a very large limousine accompanied by six motorcycle outriders arriving to return us to Buenos Aires. What we did not know then was that the area we were leaving was an infamous location, where the security services had often dumped the bodies of their victims.

JUST how lucky we were has become clear in previously secret CIA documents since released by the US government and which I have examined in detail. We now know how Argentina’s secret world was organised and some of the murderous plans it had drawn up in the event of full-scale war with Britain.

The CIA analysts identified the key department responsible for black operations as the 601st Intelligence Battalion of the Argentine Army. This special unit, whose activities were shrouded in secrecy and widespread fear, had been for years at the centre of the Dirty War, collecting information on opposition groups and employing death squads to eliminate them. According to the American intelligence officers, the 601st was readying itself to murder 500 British residents in Argentina at the time we were kidnapped. At that point, the apocalyptic secret plans had not been carried out. Instead, we had been terrorised, humiliated but, at the last moment, spared.

A CIA report, dated nine days after our kidnapping, states that it was carried out by a team working with the 601st and names its leader as a secret-service killer called Anibal Gordon, a man who was to become infamous for his bloodstained ruthlessness.

Former Argentine dictator Gen. Leopoldo GaltierI

This document was in the form of a cable sent to Langley, Virginia, on May 21, 1982. It states that the operation was ‘executed by an Argentine paramilitary group under the command of “Anibal”… The journalists had been under heavy surveillance by personnel from the Argentine Army 601st Intelligence Battalion before being selected by Gordon’s group as specific targets for kidnapping’.

A further CIA document reported divisions within the junta, with senior air force officers who were now carrying much of the burden of the war said to be unhappy with the attack on us.

‘Air force officers privately commented that it appeared as though President Leopoldo [Galtieri] was being undermined by the intelligence apparatus of his own military service by its permitting such unfortunate behaviour at the worst possible moment.’

This is the only explanation I can find for our survival.

General Galtieri himself tried to minimise the damage caused by our kidnapping which took place as his government was trying to negotiate at the United Nations. Late at night, after our return to Buenos Aires, he invited me and my crew to the Presidential Palace to apologise for what had happened to us. In what turned into a world exclusive interview, he told me that we had been kidnapped by a small group that did not want peace.

That ‘small group’, it is now clear, was inside his own secret service, men who were determined to prevent him from making any concessions to Britain.

Five of the previously secret US documents refer directly to our case. I read them and then read them again, scarcely believing that these almost 40-year-old files contained the answer to one of the nagging mysteries of my life. I examined photographs of the man they identified and found myself propelled straight back to the horrifying moments in the back of the Ford Falcon and to the field near Pilar. Looking at Anibal Gordon’s image, I felt a stab of recognition and fear.

I set out to cross-reference the American documents that mentioned him in connection with a series of crimes, with Argentine judicial records and with 40 years’ worth of newspaper articles from publications large and small across the country.

The picture that emerged was of a professional killer, both cruel and charismatic, valued by his superiors in the military secret services for the ruthless efficiency that he displayed in seizing victims, extracting information by torture and disposing of the finally valueless corpse.

‘Gordon has no enemies,’ it was said of him approvingly. ‘The ones he had are all dead.’

He first came to public notice in February 1971 as the man who planned and led Argentina’s most spectacular bank robbery of modern times. The target was the Provincial Bank of Rio Negro and Gordon’s gang made off with 88 million pesos, the equivalent at the time of more than £7 million. Recruited out of prison by the military secret service, Side, he also joined the notorious secret Argentine Anti-communist Alliance, known as the ‘Triple A’, and became perhaps the leading practitioner of the black art of kidnapping in the Dirty War.

Later, following the Falklands defeat, kidnapping to extort money became an industry, and Gordon was a kidnapper-in-chief. Reading about the former car workshop he took over and turned into a secret torture and execution centre in the Dirty War is a chilling experience, especially for those who can claim to have had a taste of Gordon’s methods.

Even today, investigations into his murderous activities are taking place and he is believed to have been personally responsible for scores of killings and to have organised and supervised many more.

Gordon died in prison in 1987, and in recent years the man who snatched us off the street and threatened to execute us has achieved a macabre posthumous celebrity in Argentina.

There of course never was, and never could be, any recourse to justice for our terrifying treatment at the hands of the Gordon gang and the elements of the junta whose orders they were following. The principal actors in the operation are either dead or serving sentences that they are unlikely to survive.

Looking back, I can say that what happened on that day in Buenos Aires left an indelible mark on me. We left Argentina a few days after the event and I took a holiday with my wife in the West Indies. There, in the middle of the night, I suddenly found myself crouching wide awake in the bedroom of our hotel in a fight-or-flight position. I had no recollection of how I got there, but my wife told me that I had leapt out of the bed in one motion seemingly while still asleep.

Less than a month later, in that age before PTSD diagnoses and therapy, I was back at work on another story.

Forty years on, I retain a strange sense of gratitude for the whole experience. I am one of those who went into journalism out of desire to be a witness to history – and this was history at its most raw. In our case, the worst had not happened but we had been given a unique insight into Argentina’s wars and the methods of one of its principal dirty warriors.

It was and remains all too easy to imagine the terrible fate that so many others suffered at the hands of Gordon, who would, more than likely, have been given the job of disposing of dozens of British civilian prisoners if his battalion’s secret wartime threat to ‘disappear’ them had been carried out.

In the end I can only be thankful that on that day Anibal Gordon chose, or was instructed, only to terrorise and not to murder us, and that we emerged alive to tell the tale.

Kidnapped By The Junta, by Julian Manyon, is published by Icon Books, priced £20. To order a copy for £18, visit mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937 before April 3. Free UK delivery on orders over £20.

Source: Read Full Article