Meet the OTHER Winston Churchill: RICHARD KAY’s fascinating look at a man who was once so famous our future Prime Minister wrote to him and volunteered to change his own name so the public wouldn’t mix them up

- American author Winston Churchill was well known in the early 20th century

- Our greatest statesman wrote to him in 1899 to offer clarity over shared name

- Britain’s Churchill would now sign off literary works as Winston S. for clarity

- They would eventually meet in person in Boston, US and years later in London

Just imagine, if you can, that there was not one Winston Churchill but two, born just three years apart.

Both were married with three children and both were accomplished writers with military backgrounds and a love of politics, both smoked – one cigars the other a pipe – and later in life they were proficient amateur artists.

Now try to picture this: that long before the Churchill we all know became Britain’s greatest and most revered statesman, the other Churchill, an American author, was more famous than his namesake and had a global following.

Indeed, such was his celebrity that our former war-time leader – voted the greatest Briton of all time in a BBC poll – wrote to the novelist proposing that to avoid confusion over their names, he would in future sign ‘all published articles, stories or other work’ by using his full surname: Spencer-Churchill.

Looking through the prism of history it seems inconceivable now that the British Churchill, who for generations has symbolised our nation’s resilience during World War II, should play second fiddle to anyone, let alone a writer who died in virtual obscurity 75 years ago this week.

But for the early part of the 20th century the U.S. Churchill was by far the better known.

His books sold in their hundreds of thousands and for the first 15 years of the century he was acclaimed as ‘America’s most popular serious author’.

So perhaps it was with some trepidation that Britain’s Churchill sat down to write that letter in the spring of 1899.

He was 24 and had not long returned from the Sudan where he had served in Kitchener’s campaign, fighting on horseback with the 21st Lancers in the Battle of Omdurman while also reporting for London’s Morning Post newspaper.

He had written his first novel Savrola, about revolution in a fictional European state which was being serialised in Macmillan’s Magazine, and his military history of the Sudan War was due to be published later in the year. He was also seeking a parliamentary seat.

His U.S. counterpart, three years his senior, meanwhile, had just completed Richard Carvel, a historical epic that was set against the backdrop of the American War of Independence and was to sell over two million copies.

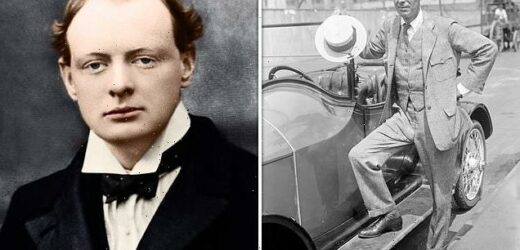

For the early part of the 20th century the U.S. Churchill was by far the better known. His books sold in their hundreds of thousands and for the first 15 years of the century he was acclaimed as ‘America’s most popular serious author’. The American novelist Winston Churchill is pictured in New York City, 1916

The future wartime leader’s letter began: ‘Mr Winston Churchill presents his compliments to Mr Winston Churchill and begs to draw his attention to a matter which concerns them both.’

It continued in courteous tone: ‘Mr Winston Churchill will recognise from this letter — if indeed by no other means — that there is a grave danger of his works being mistaken for those of Mr Winston Churchill. He feels sure that Mr Winston Churchill desires this as little as he does himself.’

He then proposed that he would become Winston Spencer-Churchill in all his writings — in later years this was simply abbreviated to Winston S. Churchill.

The American Churchill’s reply was also polite.

‘Mr Winston Churchill is extremely grateful to Mr Winston Churchill for bringing forward a subject which has given Mr Winston Churchill much anxiety,’ he began.

Accepting the offer, he added that ‘had he [himself] possessed any other names, he would certainly have adopted one of them’.

Thus was confusion avoided and, in a sign of those gentlemanly times, no lawyers were needed to reach agreement — just two men’s word and the whole matter was settled amicably.

Perhaps it was with some trepidation that Britain’s Churchill, then aged 24, sat down to write a letter to his American namesake in the spring of 1899. Pictured: Sir Winston Churchill as a young man

A year later Britain’s Churchill travelled to America — his mother’s home country — and during a visit to Boston met the other Winston, recalling in his memoirs: ‘He entertained me at a very gay banquet of young men and we made each other complimentary speeches.

‘Some confusion, however, persisted; all my mails were sent to his address, and the bill for the dinner came to me.’

A few years later the two men met again, this time in London when our Churchill was by now a prominent politician who had notoriously crossed the House of Commons from the Conservative benches to the Liberals.

At the time the American had joked about the two Churchills. ‘I have come to the conclusion that the world can hold two of us, but no more,’ he declared.

In truth the two men had little in common — apart from their mutual admiration for each other’s writing. The U.S. author was born in St Louis in November 1871 and was descended from John Churchill, one of the Pilgrim Fathers.

Our Churchill was born three years later at Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire, his family’s ancestral home. He was a direct descendant of the first Duke of Marlborough.

While the future PM attended the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst before being commissioned into the Queen’s Own Hussars, America’s Winston Churchill graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis where he rowed in the first eight and was an expert fencer.

And as young Winston was making his name as a soldier, there were signs of a literary career beckoning for the American Churchill.

He was managing editor of Cosmopolitan, in those days a staid monthly magazine for fiction, before resigning to write novels, poetry and essays.

His first book The Celebrity appeared in 1898 and five more historical novels followed, each the top best-seller in the year it appeared.

They also made him rich.

He built a substantial home in New Hampshire where he and his wife Mabel and three children settled and which for two years he let to American president Woodrow Wilson as a summer house.

He also had political ambitions, winning election to the state legislature in 1903 and 1905 where he attacked corruption and humbug with the fervour of his British namesake.

But an attempt to run for governor of New Hampshire in 1912 ended in failure and he did not seek public office again.

By now the British Churchill had achieved high office — he had been Home Secretary from 1910 to 1911 when he stood with police during the Siege of Sidney Street, a gunfight between Latvian revolutionaries and the Army, and afterwards became First Lord of the Admiralty.

He resigned from the post to re-join the Army, returning to active service on the Western Front. Around the same time the other Churchill toured the World War I battlefields and wrote his first non-fiction work — about what he saw.

The experience almost certainly informed what became his strong pacifist views by the outbreak of World War II.

Winston Churchill became Britain’s greatest and most revered statesman. He is pictured above smoking an iconic cigar in 1949

In 1919 he decided to stop writing and largely withdrew from public life. Instead he took up watercolours and became known for his landscapes. His art was, however, not as proficient as the English Churchill’s.

In 1940 he stirred from retirement and wrote the last of his 11 books, The Uncharted Way, which subscribed to his pacifist theories of non-resistance.

Seven years later he was dead following a heart attack, by then a reclusive and largely forgotten literary figure. His British namesake would outlive him by another 18 years.

Such was the British Churchill’s fame during the War years when his speeches and iron will drew the admiration of the free world, a society started in the U.S. called Churchills Of America.

It was formed by Americans bearing the same name as the British PM and raised considerable sums of money for the war effort in the UK.

Among its members and most generous of supporters, was a retired author who never objected to being known as ‘the other Winston’.

Source: Read Full Article